The Cornish in Mexico:

Celebrating Two Hundred Years of Shared History

This year marks the bicentenary of the arrival of the first Cornish mineworkers in Mexico. After visiting several mining areas within Mexico on two separate trips, and having an ancestor who participated in the migration to the Real del Monte silver mines, I am very excited to think about how this remarkable historical legacy might be celebrated.

© Dr Sharron P. Schwartz

The Beginning of a 200-year-old Legacy

Cornish mining’s links with Mexico go back to the second decade of the nineteenth century. Following the collapse of the Spanish Empire and the decade-long struggle for independence which was won in 1821, the once mighty Mexican mining industry was on its knees; technologically stagnant, and starved of capital and labour. The Mexican government looked to Britain, then the world’s most successful economy and the ‘workshop of the world’ to supply the capital, technology and skilled labour required to rehabilitate its mining economy. This resulted in several British-backed companies being floated on the London Stock Exchange, including the Real del Monte, Anglo-Mexican and Bolaños. These companies naturally looked to Cornwall, then the world’s foremost hard rock mining centre, to supply the labour and technology required to revitalise the Mexican silver mines. The year 1824 marked the arrival of the first Cornish mineworkers to various mining centres across Mexico, including Guanajuato, Zacatecas, and most importantly of all, Real del Monte-Pachuca.

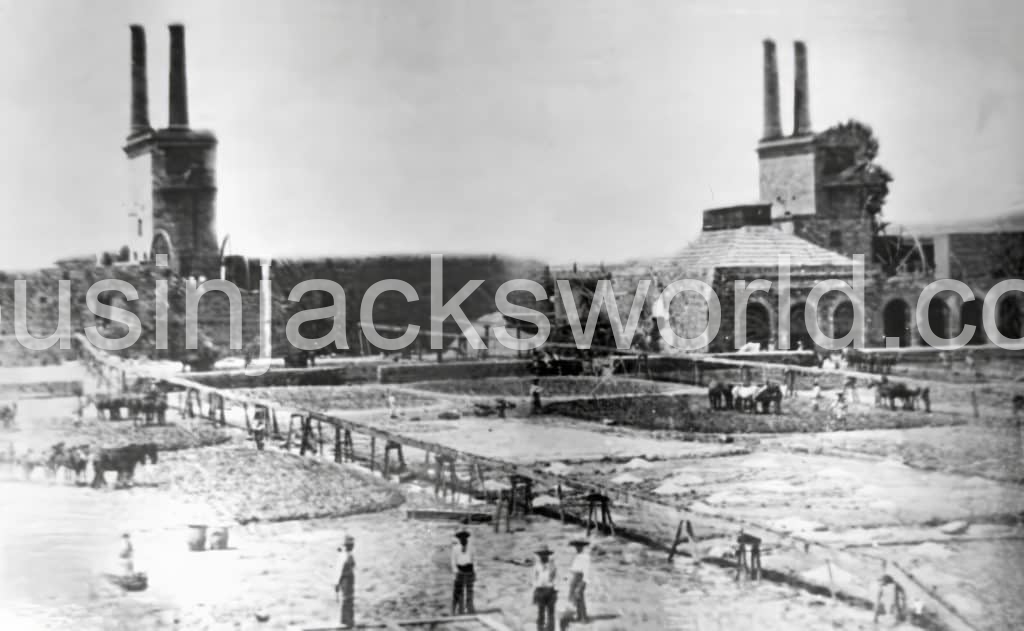

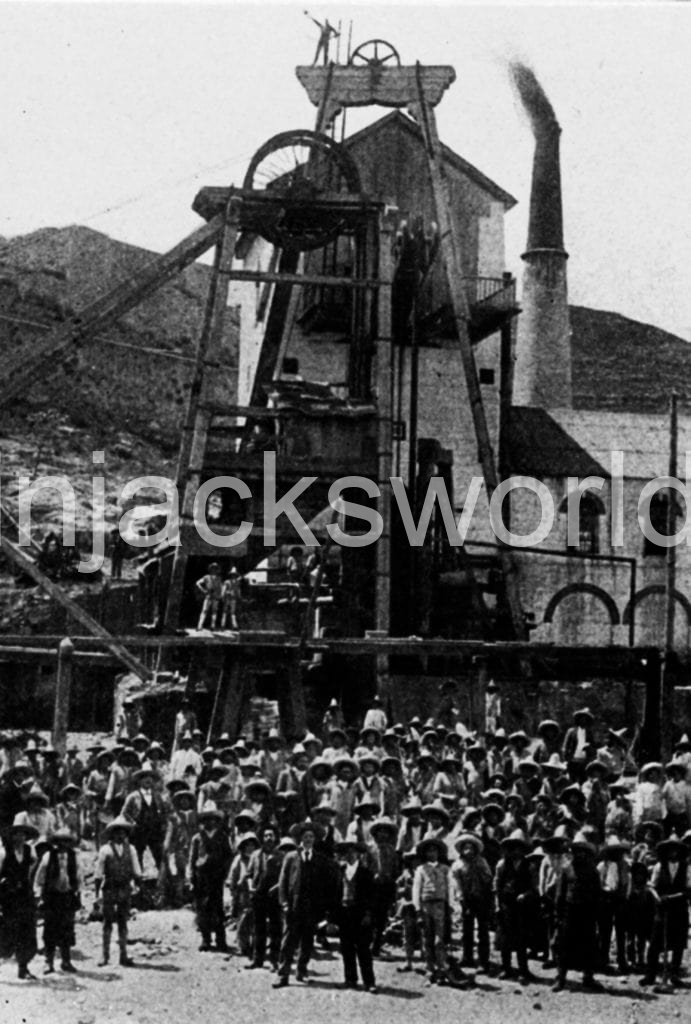

It was to the latter mineral in the Sierra Madre Oriental that the Cornish brought not only their mining knowledge, but also their steam engine technology. The mining village of Real del Monte was depopulated and partially in ruins, resembling something that had been sacked by the Cossacks, according to one of the first party to arrive there in 1824 to a rapturous welcome. The following year, the first mining machinery arrived. It was no mean feat to transport heavy, bulky steam engine parts, pitwork and other mining equipment by mule-driven carts from the coast inland to the mines located at over 2,000 feet above sea level. It came at a shocking cost to life, as roads had to be built through horrendous terrain, and the men fell victim to political in-fighting, climate, flooding and disease. Many never made it off the beach at Mocambo, having been felled by vómito (yellow fever).

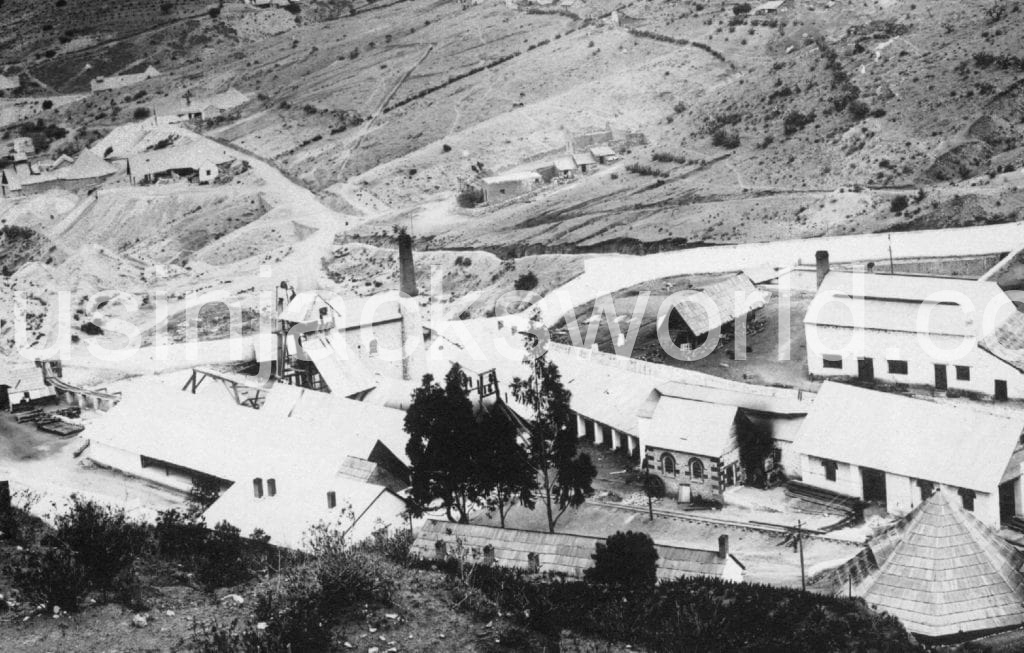

Despite these logistical problems, the Cornish succeeded in bringing the machinery of the industrial revolution to the mines of Real del Monte and Pachuca, and their steam engine technology would dominate the industry there for the next century. This mineral boasted the first engine to be installed underground in the republic (in the Rosario Mine) and in 1859, the erection of the largest single acting engine in the country: the Santa María, manufactured by Harvey’s of Hayle in Cornwall. Indeed, Harvey’s of Hayle supplied engines and other equipment to numerous mining companies throughout the Republic during the nineteenth century, including a pair of 40-inch rotative engines for the patio floor operated by the Fresnillo Mining Company in the Cerro de Proaño.

Real del Monte-Pachuca boasted the first Cornish colony in the Spanish Americas, beginning a history and shared culture that has lasted for 200 years. Even when the British mining company passed into Mexican ownership in 1848/9, the Cornish remained. As Giles Paxman LVO, the former Ambassador to The United Mexican States (2005–2009) stated, ‘ this is a tale of endeavour, fortitude and optimism to rival those of the other British explorers who fanned out over the globe throughout the nineteenth century.’

The First Transnational Community in the Spanish Americas

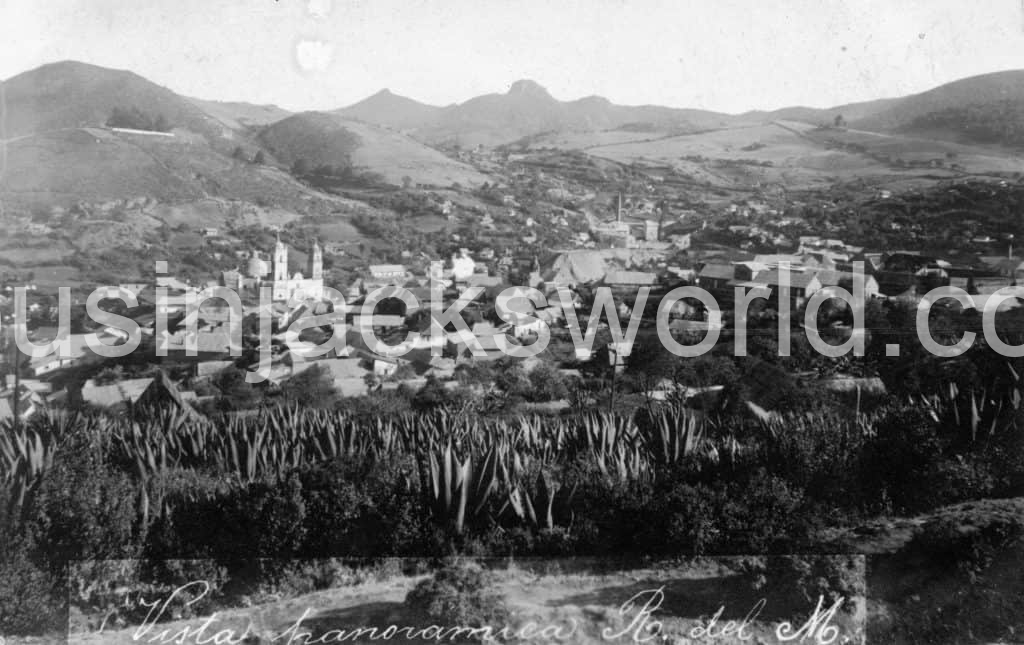

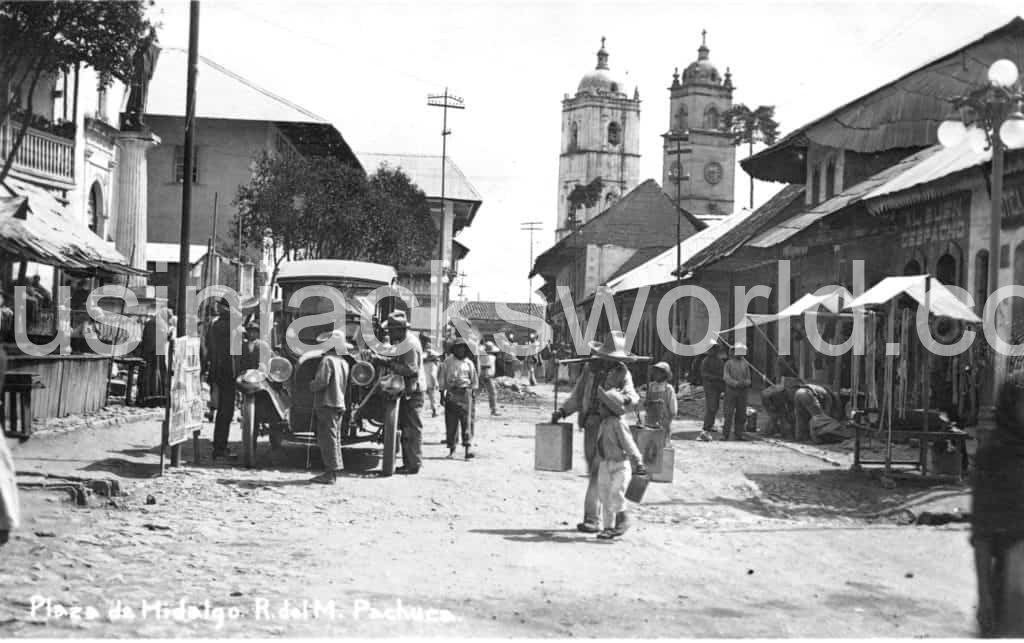

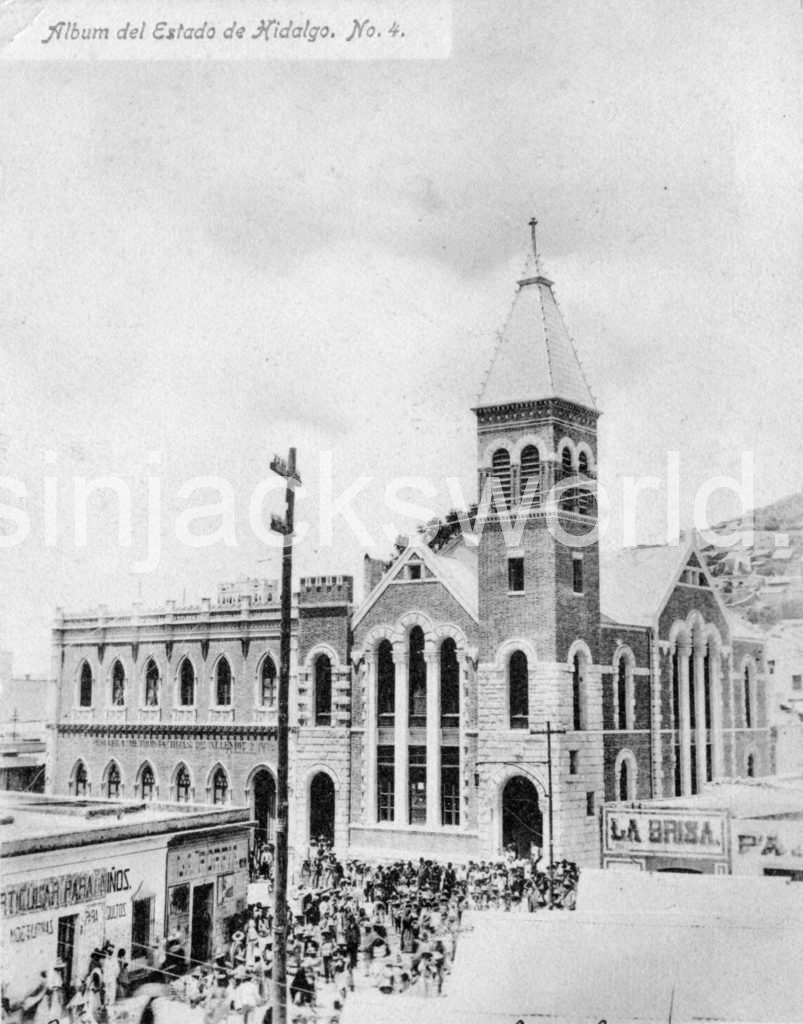

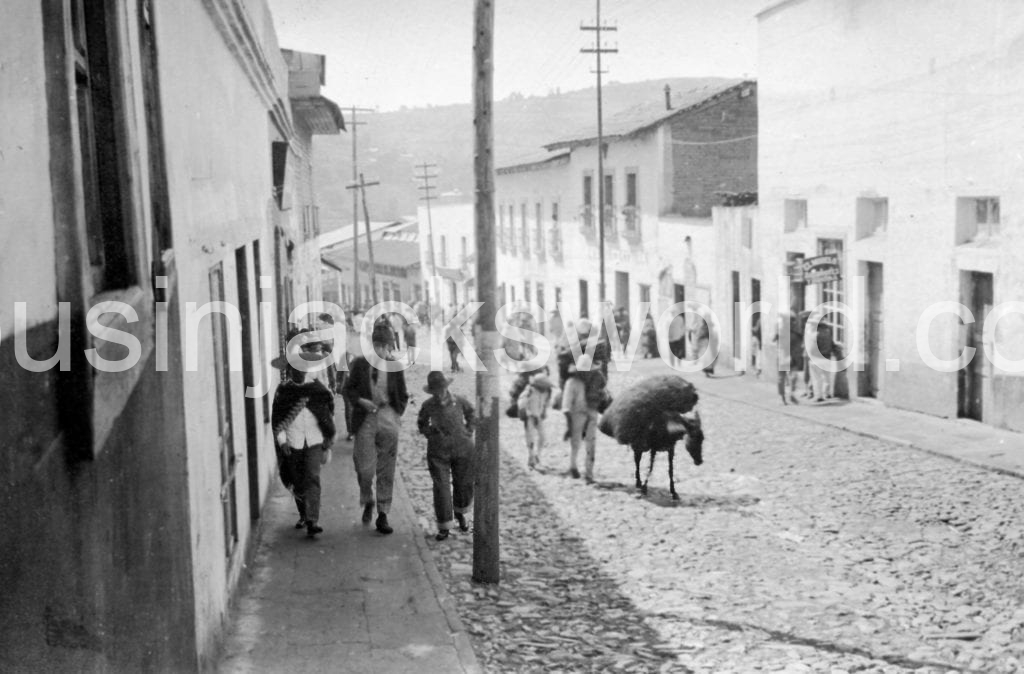

The Cornish presence remains indelibly stamped on the landscape of Pachuca and Real del Monte (now in the State of Hidalgo), in the shape of numerous Cornish-type engine houses, but also through places of worship, cemeteries and vernacular architecture.

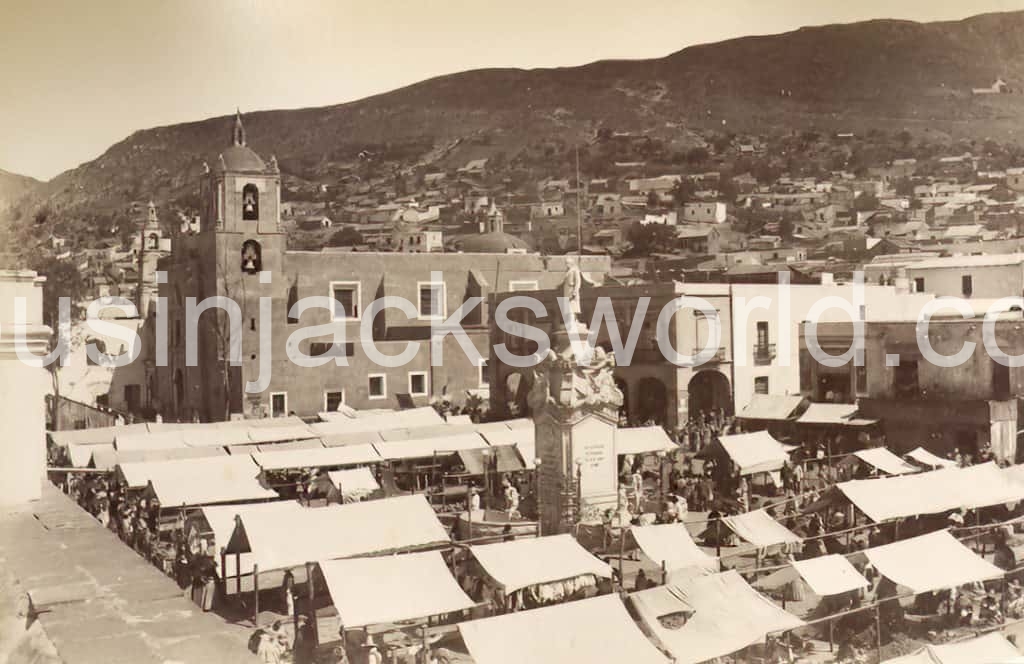

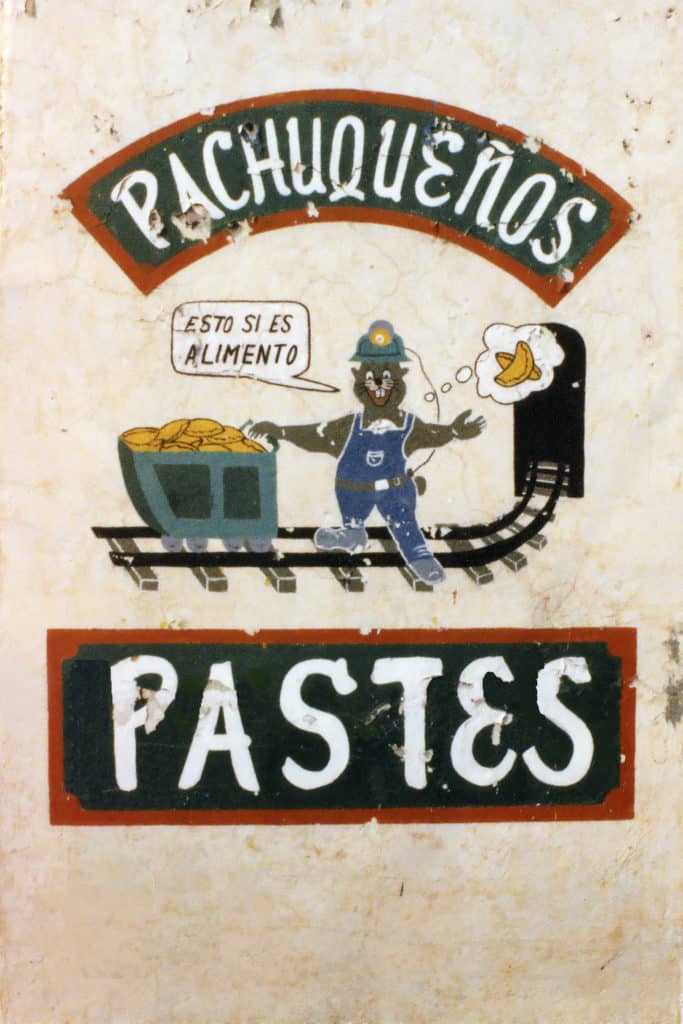

These twin settlements are also famous for their love of football and pasties (pastes), introduced by Cornish mineworkers. For well over a century, a permanent colony of a few hundred Cornishmen, many with their families, lived through epic times, as a series of mighty revolutions swept the nation and the countryside was disturbed by various factions of bandits loyal to either the conservatives or the liberals. Ladrones customarily held up and robbed the diligences travelling to the City of Mexico and Vera Cruz, and bandits thought little of shooting extranjeros, or kidnapping them for ransom. For several years following the fall of the Emperor Maximillian, there was no British consular presence in the country, which made life challenging for the Cornish who had no legal authority able to intercede on their behalf as before.

At one point, the state governor was forced to take refuge in the Company’s House in Pachuca, as the city was overrun by bandits and renegade soldiers, and the Cornish miners were involved in a shoot-out from the roof of the building which came under attack. Little wonder that they quickly learned the use of a pistol and Sharp’s rifle, and rode about armed to the teeth for their own protection. Mexico was arguably the most dangerous country in the world for a Cornishman to work in for large parts of the nineteenth century, as numerous headstones in the English Cemetery at Real del Monte attest, with the word ‘murdered’ and ‘assassinated’ etched in stone. As one Cornishman quipped, ‘So rapid were the changes of Government in those days, that when we went down the mine in the morning, we did not know what regimé we should be living under when we came up at night.’

But the wages were good enough to attract thousands of Cornishmen over the course of a century, despite the strike action the Cornish participated in during the unsettled years of the early 1870s, which caused considerable ill feeling due to poor working conditions, high taxation and an unwelcome reduction in the wages of the engine drivers. Many left the company and set up their own mining concerns. Several enjoyed great wealth and influence, including Francis Rule and Richard Honey, who left their mark on the Mexican economy in the shape of silver mining, iron founding and railway construction. Francis Rule’s elaborate private residence (now owned by the municipality and known as Casa Rule) is one of a number of elegant civic buildings he financed in late-nineteenth century Pachuca.

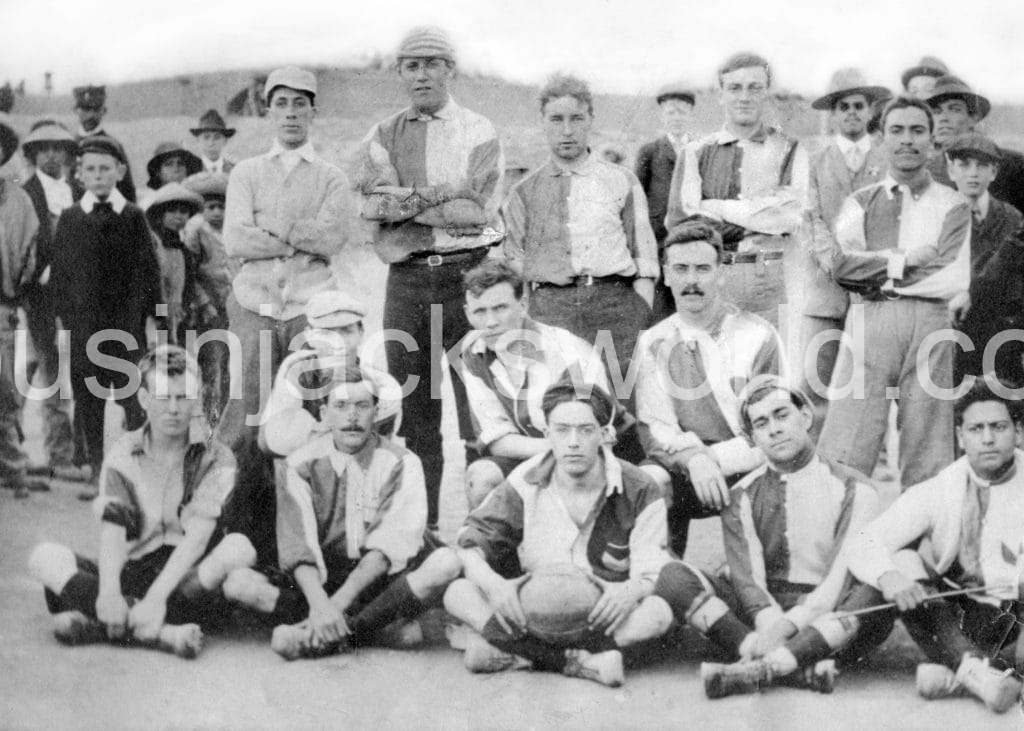

The Cornish community created its own entertainment, focused on the Men’s Institute, the Methodist Chapel, the Hidalgo Lodge (freemasons), and the Miner’s Arms in Pachuca. Cricket and football leagues were instituted, and today Pachuca prides itself as being the spiritual home of ‘the beautiful game’ in Mexico, a sport popularised by the Cornish, which led to the formation of Club de Fútbol Pachuca in 1892, nicknamed ‘Los Tuzos’ (The Gophers).

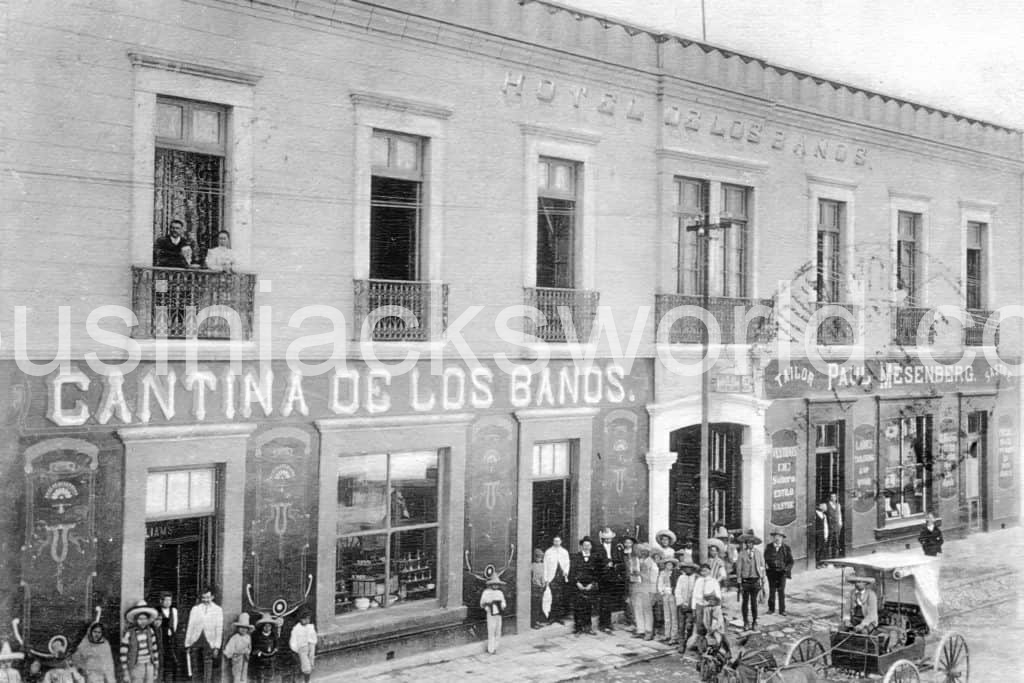

Annual events like Queen Victoria’s birthday and tea treats complete with saffron buns, were enlivened by the strains of brass band and choir. There were always a significant number of Camborne people in the Cornish colony, due to strong migration chains linking Pachuca and Real del Monte to this town and the constellation of mining villages (Beacon, Brea, Tuckingmill, Knave-go-by, Troon) surrounding it. So, it is not surprising to learn that Camborne Feast was celebrated! It was said, ‘A Camborne man feels as much at home as if he were again at Troon or Tallywarren Street.’ Some Cornishmen like Guillermo Pascoe, William Phillips, and Charles Grenfell, opened thriving stores and hotels, which became important social features of the colony.

During the heady days of migration, Camborne newspaper, the Cornish Post and Mining News, published a ‘Letter from Pachuca’ and items of interest were shared in the Cornish press from English language newspapers such as the Mexican Herald. Monies were donated back to Cornwall for a variety of good causes, and many families lived on remittances earned in Mexican mines. It was not uncommon to see return migrants wearing Mexican sombreros and serapes in towns like Camborne and Redruth, or to hear Spanish spoken in the streets and bars of both. Returning migrants celebrated their Mexican links by bestowing names on their homes such as Velasco House, Acosta Villa, Hidalgo, Zimapán, Pachuca House and Dolores House. For a while in the early twentieth century, there was a Cornish Association in the City of Mexico, which celebrated the Duke of Cornwall’s birthday, and customarily ended its proceedings with a rendition of Trelawney.

Decline and Revival

However, the arrival of the Americans to the Pachuca region in the early twentieth century, signalled the inexorable decline of the Cornish presence there. Steam technology was replaced by electrically driven pumps, American engineers replaced those from Cornwall, and the Americans sought to hire men from the USA rather than from Cornwall. Some of the Cornish returned home or drifted away to other mining areas such as El Oro or the southern USA, while many settled in the City of Mexico. Things worsened after the mines were nationalised in 1947 which placed restrictions on other than Mexican citizens.

The Cornish were not apt to change their nationality, and this was compounded by a dramatic ethnic deflection of many second or third generation men and women who found more appeal in the opportunities to integrate into Mexican society than to retain links with a homeland few had ever seen. Some of these people bore Cornish surnames which live on in Mexico today. But by the early 1970s, there were only a handful of Cornish people left in the Pachuca region.

However, following the 1977 publication of Dr A.C. Todd’s book, The Search for Silver, which sparked curiosity about the Cornish in Mexico, there has been an explosion of interest in the links that bind our two nations closely together. This resulted in the twinning of Redruth with Real del Monte and Camborne’s friendship treaty with Pachuca in 2008. An account of the visit which culminated in the signing of those ties, is recorded in my book, Mining a Shared Heritage: Mexico’s ‘Little Cornwall’ which is beautifully illustrated with historic and modern images and testimonies. It is in both English and Spanish. Buy a copy here. Today, there is a thriving muti-million peso ‘paste’ industry in the old mining towns of Hidalgo to rival that in Cornwall, and the area celebrates this heritage with an annual ‘Paste Festival.’ The beautiful mining towns of Real del Monte and Mineral del Chico are Pueblo Magicos, due to their significant silver mining heritage.

This year we will hopefully be writing an exciting new chapter in the continuing history of our two nations, as we celebrate two hundred years of the Cornish in Mexico. For my part, I am planning a return to Mexico later this year. Perhaps an exhibition and a book, based on over quarter of a century of my extensive research, will be a fitting gesture to mark this important bicentenary?

Follow the first Cornish miners in Mexico through my series of three films celebrating their epic journey to Real del Monte in 1824

First of three films Celebrating 200 Years of the Cornish in Real del Monte-Pachuca, Mexico

Second of three films Celebrating 200 Years of the Cornish in Real del Monte-Pachuca, Mexico

Third of three films Celebrating 200 Years of the Cornish in Real del Monte-Pachuca, Mexico

Were your Cornish ancestors migrants to Mexico?

I have a special interest in Mexican mining, as one of my ancestors, Captain John Veall Inch, the son of Captain James Inch of Wheal Buller, lived in Real del Monte for twenty years, where he managed the San Jose de los Dorodores and Gran Tenochtitlán Mines. But so far, I have not been able to pin down the precise dates of his journeys to and from Cornwall. I discovered that this is by no means uncommon among the Cornish who migrated to Mexico, so I have devised a novel way of trying to do so by using lists of ‘pasajeros’ published in the Mexican press. Find out if your ancestor appears in my new database: Cornish Migrants to and from Mexico

“Mexico’s Little Cornwall”

Dr. Sharron Schwartz

Specialist in Cornish Mining Migration and transnational communities

Pingback: Bicentennial between Cornwall and Mexico