Cornish mineworkers in South Africa

A talk to the Toronto Cornish Association

“When the button is pressed in South Africa, the bell rings in Cornwall”

© Sharron P. Schwartz

I recently gave a ‘zoom’ lecture to the members of the Toronto Cornish Association, entitled, ‘The Cornish Experience of South Africa in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries.’ Drawn from my own family history, my extensive research on the Cornish overseas, and a visit to Southern Africa in 2012, the lecture focussed on three areas: the copper fields of Namaqualand, the diamond mines of Kimberley and the Transvaal gold mines centred in the Johannesburg region. The talk explored the ways in which Cornwall and South Africa became inextricably intertwined, politically, socially and economically. This made it the word on everyone’s lips throughout Cornwall, especially in the decades either side of 1900, so it was said ‘when the button is pressed in South Africa, the bell rings in Cornwall.’

The story of the Cornish in Southern Africa began in the mid-1840s in Little Namaqualand on the fringes of the Kalahari Desert. By the mid 1850s, a copper rush was underway spearheaded by Cornish labour and mines were being worked at Springbok, Concordia, and Spectakel. By the 1860s, only two companies remained – the Namaqua Copper Company and the Cape of Good Hope Copper Mining Company. The latter worked mines at Nababeep, O’okiep, and Spektakel and the former worked in the Concordia area. Both companies employed significant Cornish labour, and Cornish steam engine technology graced some of the mines, particularly O’okiep. The copper ore was transported along a 92-mile railway from O’okiep to Port Nolloth, engineered by Cornishman, Richard Thomas Hall. Today, little remains of the once thriving communities, bar one or two sand-blasted headstones to Cornish people at Spectakel and the cemetery at O’okiep. However, the industrial landscape is superlative. The jewel in all of Africa’s crown is undoubtedly the Cornish-type engine house at the O’okiep Mine containing its 50-inch engine designed by Hocking of Redruth, built by Harvey’s of Hayle, and installed by engineer, Edward Hodge, in the early 1880s. The engine is the only vertical Cornish manufactured beam engine in situ in its purpose-built engine house in the Southern Hemisphere.

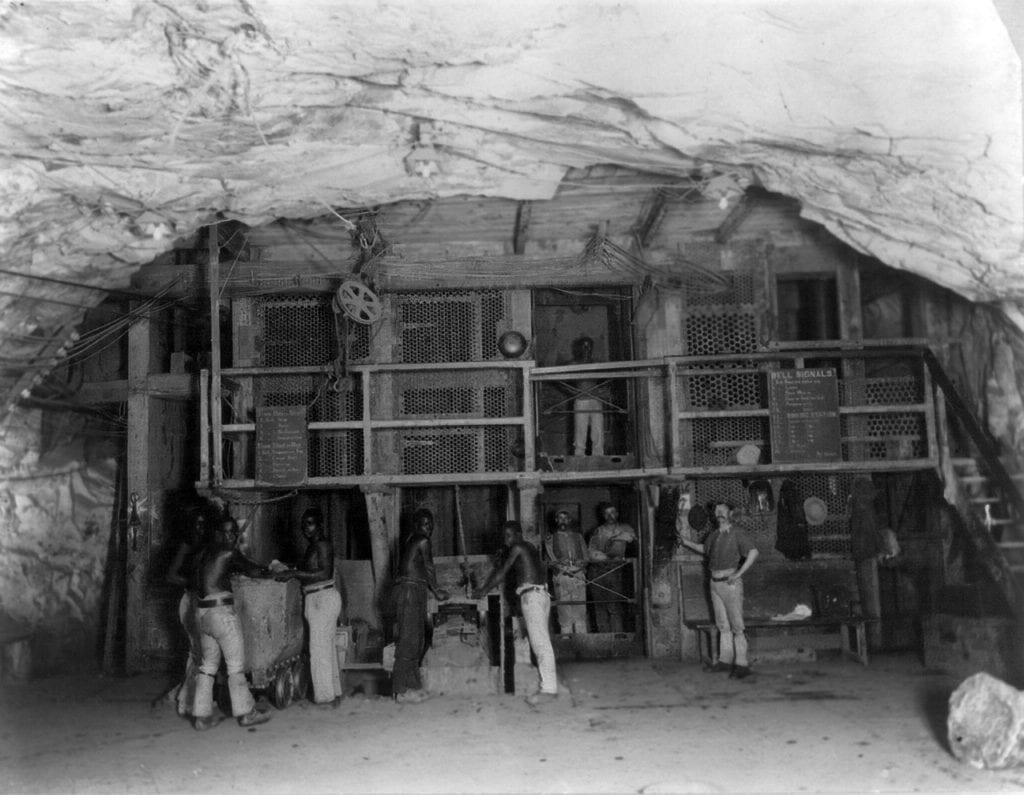

Diamonds were discovered in the mid-to late-1860s in West Griqualand, and by 1871 a diamond rush was underway on farmland brought from the De Beers brothers. The Cornish, who were already mining copper in South Africa, rushed east. They bore witness to the earliest days of diamond mining, when over 30,000 men toiled in an area roughly 300m by 200m which resembled a giant ant heap and lived in tents and tin shacks in a shanty town on the diggings named New Rush. This was renamed Kimberley in 1873. The history of diamond mining was inextricably linked to two figures: British Jew, Barney Barnato, and the controversial British imperialist, Cecil Rhodes. Rhodes eventually brought out his rival Barnato for a sum of over £3,300,000, and came to dominate the diamond mining industry as Chairman of the De Beers Company. Rhodes was responsible for bringing Cornish steam engines from Harvey’s of Hayle to the Kimberley Mine to unwater the workings which were at risk of flooding as the open cast pits were deepened. Industrial order and discipline became necessary and Cornish mine captains were recruited. One of the most famous Cornish names in South African diamond mining was that of Captain Francis Oats of St Just, who eventually took over the Chairman’s position at De Beers from Rhodes.

When the workings by necessity went underground, the Cornish truly came into their own, as their hard rock mining skills were vital, and Captain Oats saw to it that many Cornishmen found jobs with De Beers. However, conditions there were far from prefect and in 1888 a fire ripped through the workings claiming the lives of seven Cornishmen, three from St Just. The miners formed friendly societies to mitigate their poor wages. Oats did his best for his kinsmen. He insisted that De Beers give each miner a yearly paid holiday in Cornwall. He also forced the adoption of water hydrants to lay the dust created by the rockdrills, the main cause of miners’ phthisis. He became president of the Cornish Association at Kimberley and was elected to represent Namaqualand in the South African parliament, holding office until 1907. By the late 1880s, many Cornish moved east to the South African Republic (ZAR), an independent Boer state, where gold had been discovered in the Witwatersrand in 1886, ushering in a gold rush like no other.

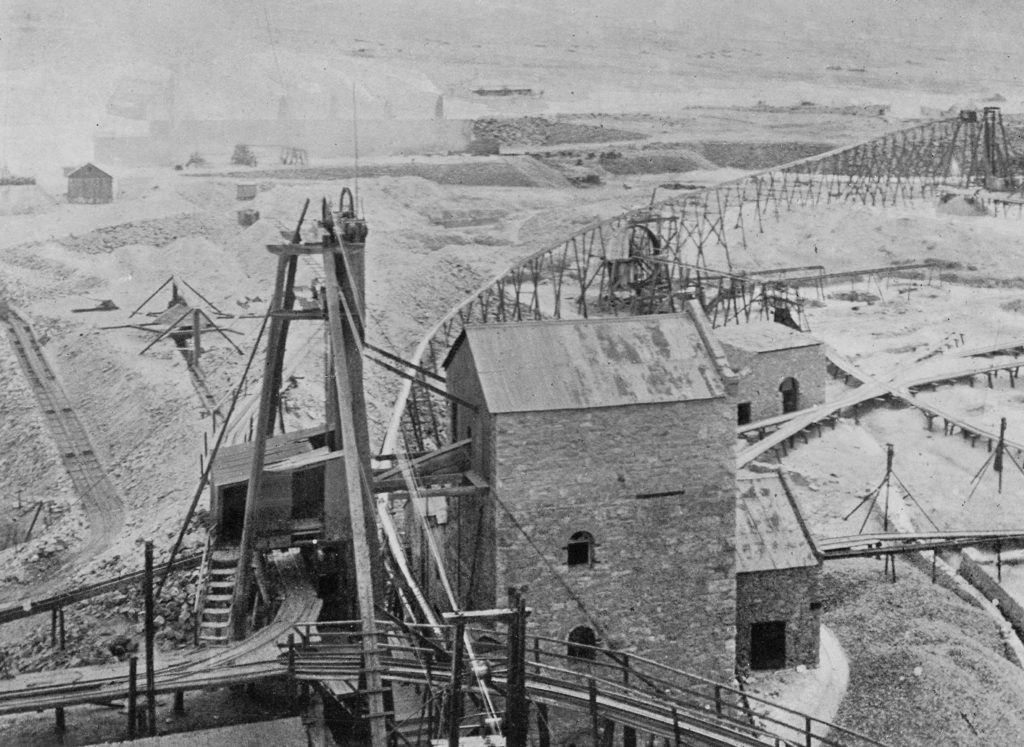

There were Cornish miners at Johannesburg when that great metropolis of over 6 million was just a couple of tin shacks and half-a-dozen tents, and the people braved enteric fever, unsanitary conditions and violence. In the two decades that followed, South Africa became one of the most popular migration destinations for Cornish mineworkers, who commuted back and forward to work ‘on the Rand.’ Aided by faster and cheaper methods of travel, with road and sail making way for steamship and rail, people were able to migrate to the Rand from Cornwall in about a week and a half. Wages were good and vital to a mining region witnessing an inexorable decline, as the first the copper industry collapsed, then tin mining entered upon its downward trajectory.

These were the heady days of migration, when Johannesburg, a city of 100,000, had a ‘Cousin Jack Corner’ at the junction of Prichard and Von Brandis Streets, and was considered to be but a suburb of Cornwall. Small wonder, as one in four white miners was Cornish. Cornish carols sounded in the streets of Johannesburg at Christmas; Fanny Moody, ‘the Cornish Nightingale’ sang to thousands of her countrymen in 1896; the Cornish Association of the Transvaal boasted a large membership; and rugby and wrestling clubs were formed. Mines such as Simmer and Jack, Randfontein, Robinson Deep, Wemmer, Crown Reef, Langlaagte, Nourse, and City and Suburban, were household names back in Cornwall, and special weekly trains were laid on to take the migrating mineworkers to Southampton for passage to Cape Town. Whole communities across the Duchy came to rely on remittances, and families eagerly awaited the banker’s drafts headed with the magic words ‘Standard Bank of South Africa.’ The shops did a roaring trade after the weekly South Africa Mail came in, prompting a local newspaper to remark, ‘We are living on South Africa.’

However, remittances, or ‘migrapounds’ as I have dubbed them, were a divisive factor in communities, as they highlighted the differences between the haves and the have nots. Miserly saving or mad spending occurred. Many families made showy displays of their new found wealth, by purchasing pianos, expensive furniture and tea sets, elaborate hats and clothing, and flaunted fine gold broaches and other jewellery. Chapels became a tournament of fashion. In South Africa too, remittances became divisive. It is said that the scale of miners’ home pay to Cornwall, which amounted to around a £1 million per annum in the 1890s, forced Boer President, Paul Kruger, to raise taxation on ‘Uitlanders’ (foreigners), thus exacerbating the tense situation between Boer and Brit, as the British paid tax without representation in the Volksraad, which became something of a running sore.

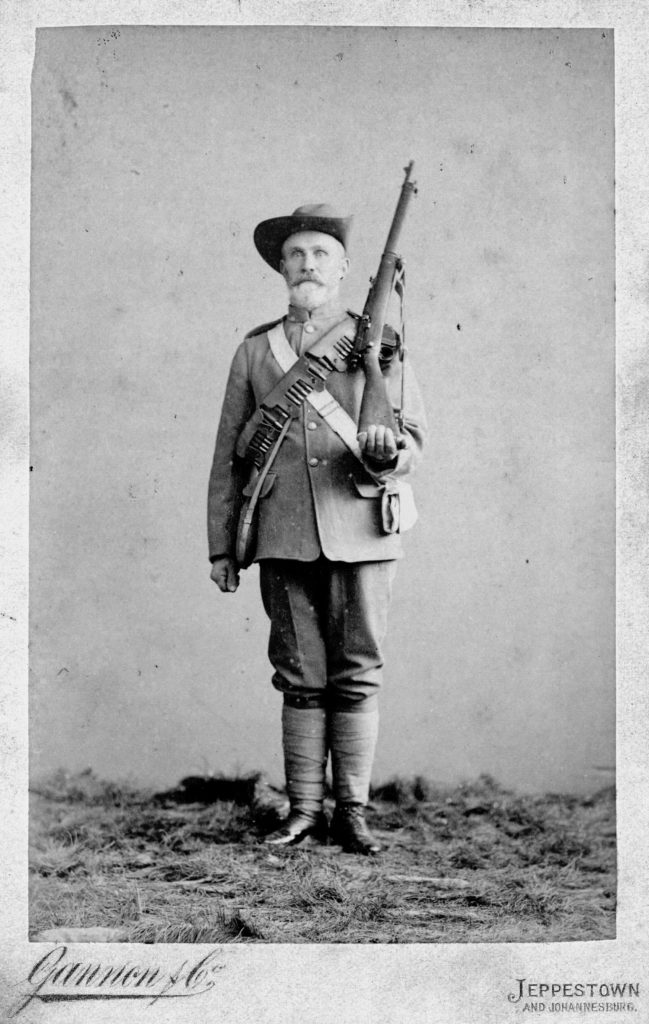

Imagine the shock in Cornwall when the political situation which had been balanced on a knife’s edge since the ill-fated Jameson Raid of late 1895-early 1896 resulted in the Boer War of 1899-1902. The Jameson Raid had thrown up divided loyalties when some Cornishmen refused to take up arms against the Boers who had welcomed them. Some of their fellow Brits were appalled at their cowardice and showed them the white feather. A group had ‘Coward’s Van’ chalked on the side of the railway carriage conveying them to Cape Town. Those who left did not deny that they refused to fight, but deplored the way they had been maligned for cowardice. They claimed the whole movement was the work of influential capitalists, whose ultimate object was simply to obtain complete control of the Transvaal goldfields, and to convert them into a Consolidated Corporation similar to the Kimberley diamond mines.

Only about 10 percent of men returned home to Cornwall. Others remained to fight, setting up for example, the 400-strong ‘Cornish Brigade’ which drilled in front of the Cornish Association buildings and at the back of the Wemmer Mine. It paraded through the principal streets of Johannesburg accompanied by the One and All band playing Trelawney. The men wore a white ribbon with the 15 balls on their right arm. However, it soon became clear that trouble was brewing once again. British desire for further influence on the African continent and its resources led to operations aimed at expanding their territory into the independent Boer republics of the ZAR and the Orange Free State. This culminated in the Anglo-Boer War which broke out in 1899 and lasted until 1902. The Cornish were once again stuck in the middle, caught between favouring the Boers, or supporting the wider imperial interests of Britain. The Boer War split Cornish communities and also families in a manner much like Brexit has done today.

This cruel war culminated in concentration camps and genocide and served as an augur of the horrors of war that the 20th century would present. Almost 50,000 innocent people lost their lives in concentration camps due to overcrowding, malnutrition and rampant levels of diseases. The shining light of the conflict was Emily Hobhouse, a descendant of Sir Jonathan Trelawny (of 20,000 Cornishmen fame). She visited the camps and was appalled by the treatment of captives. She created the South African Women and Children’s Distress Fund, and initiated a campaign to bring awareness about the conditions.

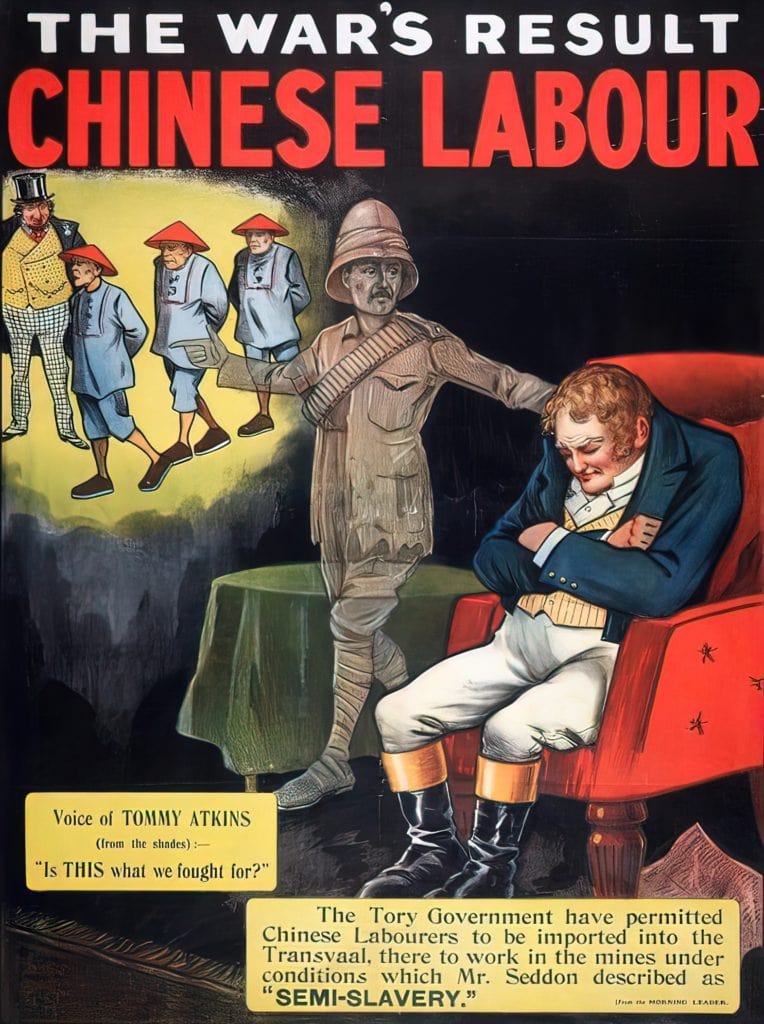

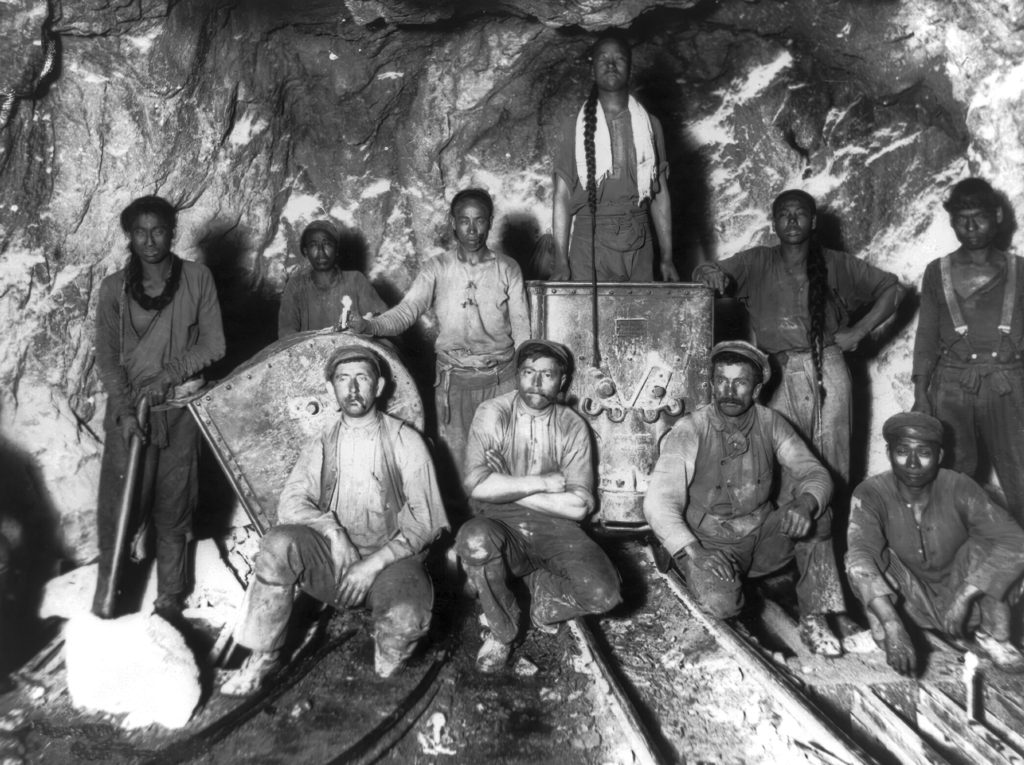

The unsettled political situation sounded alarm bells when unemployed Cornishmen returned home from South Africa, for the remittances that flowed back to Cornwall from the land of gold were seen as vital to a region in the economic doldrums. It is no surprise to learn that South African affairs came to dominate local politics for several years, with general elections in the early 1900s being fought over issues occurring thousands of miles away on another continent. These included allowing indigenous men to work rock drills which forced the Cornish into supervisory positions, and particularly the introduction of Chinese labour on the Rand. This latter issue split the Mining Division in the years 1900 and 1903, with the Radicals supporting a ban on Chinese labour and the Unionists supporting it. It is fair to say that these elections, with their overtly racist overtones against the ‘Coolie’ Chinese, kaffirs (indigenous blacks) and ‘Peruvians’ (the Jewish ‘Randlords’), were not the Mining Division’s finest hour.

By the first decade of the twentieth century, it became apparent that many Cornishmen had paid a terrible price for those Standard Bank of South Africa remittance cheques, as many who had operated rock drills came home afflicted with miners’ phthisis, caused by inhalation of the hard quartz dust which ravaged the lungs. Miners operated rock drills often without a water jet to dampen the dust. The rock drill became known as the ‘widow maker.’ In 1912 the average working life on the Witwatersrand gold mines of a rock driller was seven years, and the average age at death was 33 years. This led to legislation in South Africa which eventually allowed for compensation to the men and their families who had been affected.

The First World War interrupted migration flows worldwide and claimed many Cornish lives. After the war ended, things were never quite the same again. It was clear that the glory days in South Africa were over. A series of labour strikes, a fall in wage rates, declining job opportunities, and a belated recognition of the dreadful price paid to miners’ health due to phthisis, gradually saw the umbilical cord to the land of gold wither away.

Overall, the Cornish links with South Africa are less tangible than those in parts of Australia, Mexico or the USA for example. The O’okiep engine house, Cornish pasties in a halal bakery in Johannesburg, a handful of cemeteries, the Baragwanath Academic Hospital near Soweto (named after a Cornishman), and the smattering of house names that still embellish the transom windows and gateposts of houses in the old mining Cornish districts, bear witness to this remarkable era in Cornwall’s history. But perhaps the links that persist the most, are those that remain carved deep into the hearts of Cornish families like mine. Two of my great great uncles perished in South Africa in 1907 within six weeks of each other: John Michael Harvey from enteric fever in Randfontein Hospital, and his brother Bill, blown up in an underground explosion in the Dreifontein Mine. They lie buried in Randfontein and Boksburg respectively. It is vital to remember and celebrate this important and at times complicated and troubled relationship with South Africa, as it did so much to shape both nations.

My thanks to the Toronto Cornish Association for inviting me to give this presentation. Follow them at: https://www.facebook.com/TorontoCornishAssociation/