Cornish Mining Migration: Cornwall’s Great Migration

Unless otherwise stated, all content is © Sharron P. Schwartz and may not be reproduced without permission

Cornish Mining Migration: A Global Phenomenon

“Some say of the Cornish miner

His home is the wide, wide world,

For his pick is always ringing

Where the Union Jack’s unfurl’d.”

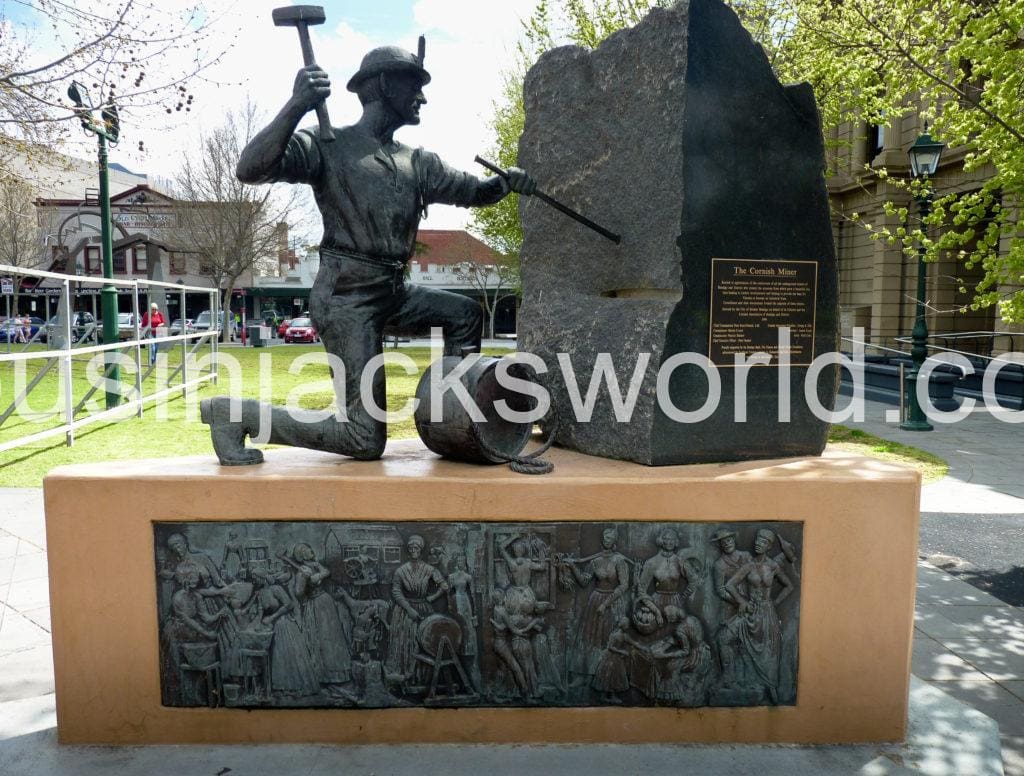

These triumphant lines of verse, written in 1896 by St Day journalist, Herbert Thomas, illustrate the sense of pride Cornish people take in the worldwide travels of the ‘Cousin Jacks’, an affectionate term for our mineworkers who conquered the global hard rock mining industry in the century from 1815. This is the period we call ‘Cornwall’s Great Migration’, and, according to Cornish mining lore, there wasn’t a hole in the ground anywhere in the world that didn’t have a ‘Cousin Jack’ working away at the bottom of it.

By the turn of the twentieth century, in communities the length and breadth of Cornwall, virtually everyone from a mining background had a relative, or knew of someone, who had gone overseas or ‘up country’ to work. For in the century after 1815, Cornwall was one of Europe’s great emigration regions. About a quarter of a million people left Cornwall for overseas (with a similar number migrating within the British Isles). Many of these migrants were connected to the mining industry.

For a region that covers less than 1,400 square miles and a population that never exceeded 375,000 in the 1800s, it is remarkable that we have stamped our mark so visibly on one industry, and spread our mining culture worldwide.

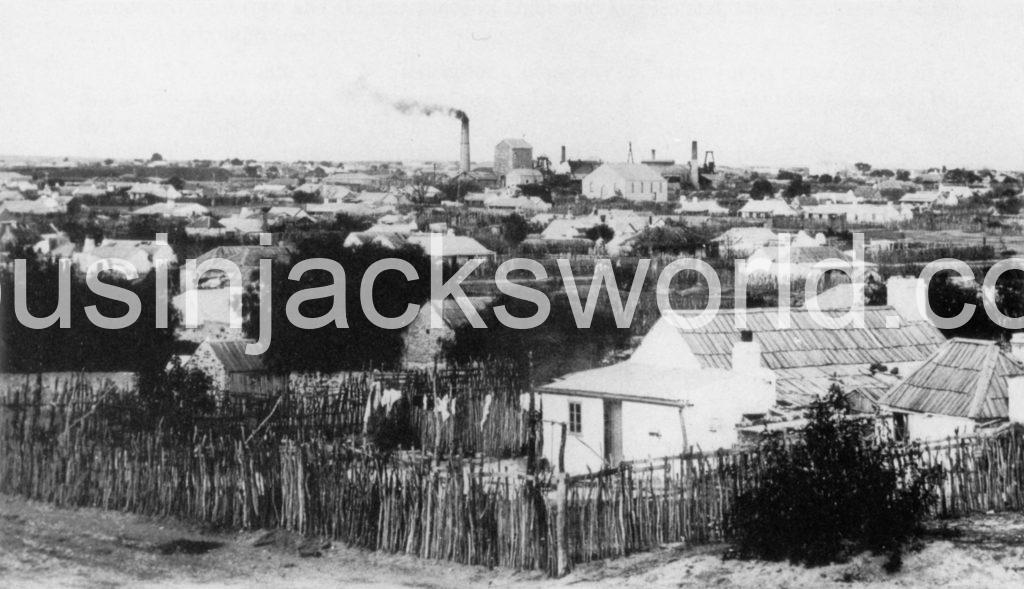

Today, you can buy an authentic version of a Cornish pasty in Real del Monte, Mexico; Burra, Australia; Johannesburg, South Africa; or Grass Valley, California. Methodist chapels grace the skylines of Moonta in Australia, Pachuca in Mexico, and Wisconsin, USA, and Cornish-type engine houses face majestically seawards at opposite ends of the earth, at Allihies in west Cork, Ireland, and at Kawau Island, New Zealand. Traces of our culture are everywhere, and the stories of our overseas experiences are the very stuff of Hollywood and run the gamut of human emotion.

Cornwall: Engine House of the Industrial Revolution

The Cornish mining industry is thousands of years old and by the mid-1700s, as Britain began her rise to prominence as the world’s foremost industrial power, we had solved the problem of flooded workings, mastered mining deep underground via shafts, and ensured a constant supply of the minerals, particularly copper, required to fuel the British industrial machine.

The Silicon Valley of its day, Cornwall was a region at the forefront of mining engineering and cutting-edge technology and gave the world the high-pressure Cornish steam engine, a true giant of the industrial landscape. Accommodated in its characteristic masonry house, this type of engine was used for pumping, winding and crushing operations. It came to mark strange and exotic landscapes worldwide, enabling underground mining on every habitable continent.

As the British hard rock mining industry began to gather pace in the mid-1700s, so the first trickle of mineworkers began leaving Cornwall. This was a migration stream of the highly skilled who initially moved about mainly within Britain and Ireland, helping to develop various mining enterprises.

Trevithick and the Transatlantic Migration of the Industrial Revolution

But it was an 1814 transatlantic agreement, the first of its kind, spearheaded by the brilliant Illogan-born engineer, Richard Trevithick, that was pivotal. His innovative high-pressure engines successfully unwatered abandoned silver mines at high altitude in the Peruvian Andes, a feat that was thought to be scientifically impossible. Trevithick was responsible for the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in Latin America. He created a fertile seed bed which nourished our reputation as a hard rock mining and engineering centre of excellence, which ensured the future migration of tens of thousands of Cornish mineworkers.

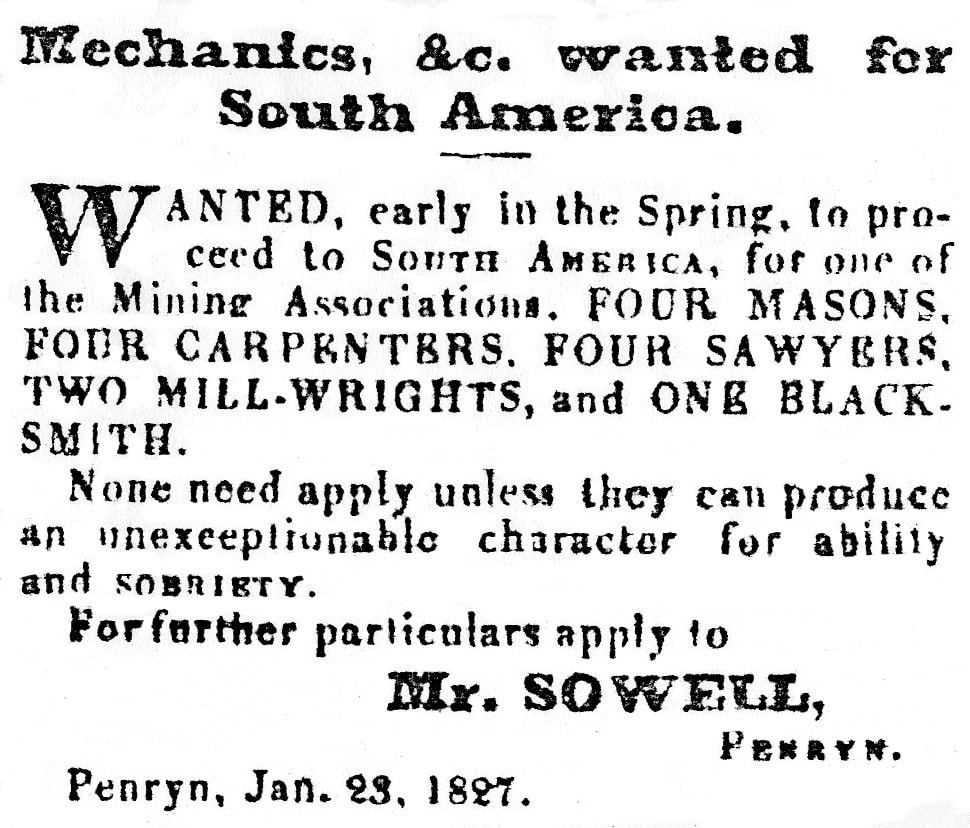

Indeed, this reputation was cemented during the mining craze of the mid-1820s. This had been stimulated by the London Stock Market boom which saw British capital penetrate the markets of the newly-independent nations of Latin America for the first time. One third of the British mining companies to emerge at this time had Directors who were either Cornish, or who were intimately connected to the Cornish mining industry.

These factors ensured that Cornish mineworkers took ship with their mining technology and equipment for mines in Chile, Peru, Brazil, Colombia/Venezuela, Mexico and Argentina. At a time when our copper mining industry was at its zenith, they could only be enticed overseas with offers of far higher wages than those they received at home, or by promotion to a higher rank. Some of the earliest expatriate Cornish communities – Real del Monte in Mexico and Gongo Soco in Brazil – date from this time.

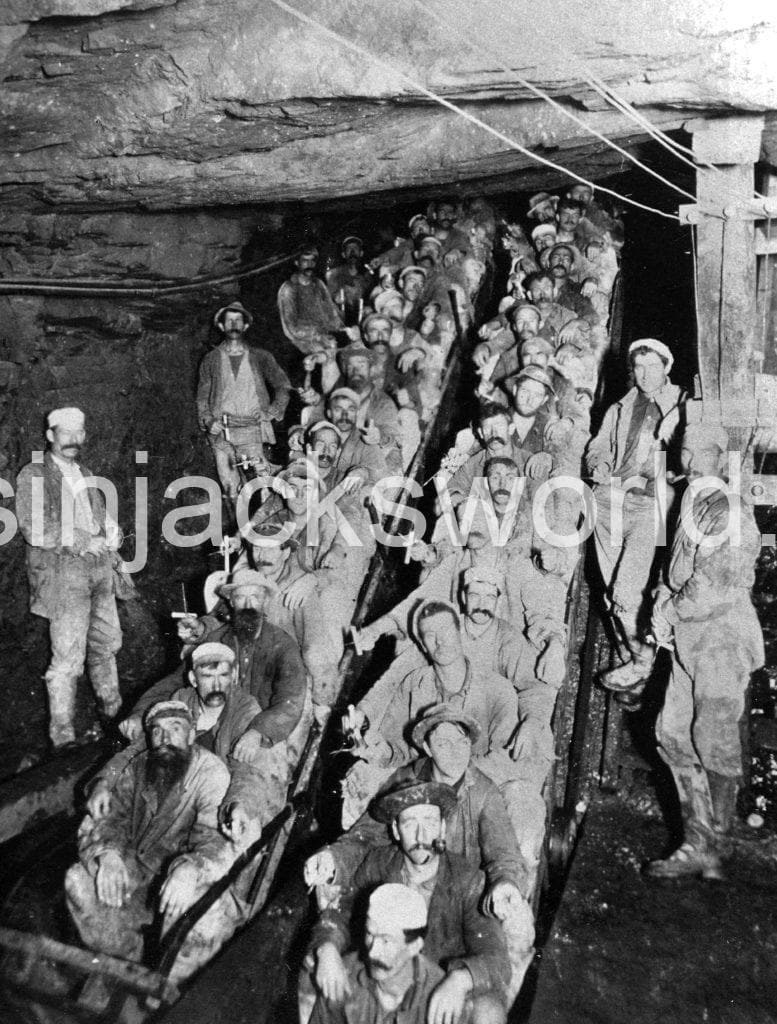

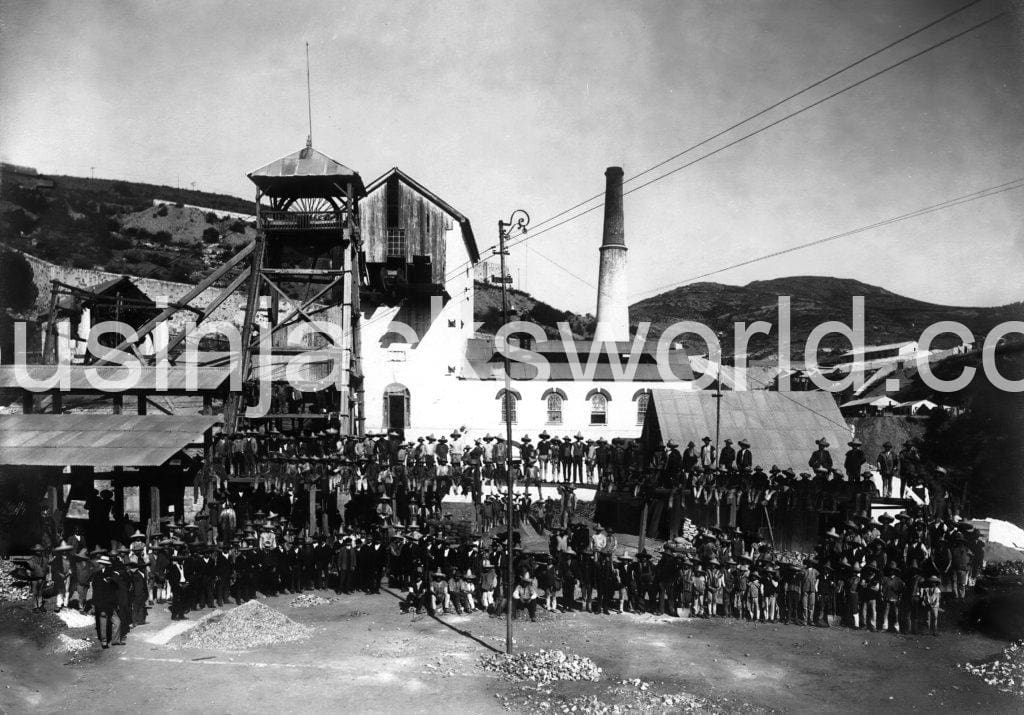

In the mines of Latin America, Cornish mineworkers added a knowledge of the geology and mineralogy of gold and silver ores to their considerable skills in the locating, mining and dressing of tin and copper ores, and came to be viewed as the world’s finest hard rock miners. This status was jealously guarded and relentlessly promoted by us, thus ensuring that we dominated the emerging international mining labour market.

In the 1830s the copper mines of the Caribbean, especially Cuba, were attracting Cornish attention, and the lead regions of the Upper Mid-West in the United States were drawing in many more who settled towns like Mineral Point, Wisconsin. From there, and from the mining fields of South and Central America, Cornish miners rushed to California when surface gold was discovered in 1848. But underground mining along the famous ‘Mother Lode’ was only made possible by the application of our pumping technology, and towns soon mushroomed along its length including Grass Valley, which quickly became a ‘Cousin Jack’ town.

Changing Patterns of Cornish Mining Migration

During the economically depressed years of the ‘Hungry Forties’, a decade of food shortages, high prices and unemployment, Cornish families made use of government-promoted free and assisted passage schemes targeting the able-bodied poor. Although some of these migrant families were undoubtedly from a mining background, they declared themselves to be agriculturists or craftsmen, trades which the fledgling colonies in Canada, Australia and New Zealand required.

However, the discovery of copper in Kapunda and Burra in South Australia in the mid-1840s signalled the development of commercial mining in Australia. Cornish settlers eagerly swapped their pitchforks for picks as the mining industry took off. Gold was soon discovered in Victoria and New South Wales, ushering in frenetic gold rushes. This was followed by further mineral strikes across this continent and in neighbouring New Zealand. Over the coming decades some of the largest and most visibly Cornish expatriate communities in the world emerged ‘Down Under’. These included Burra and Moonta, dubbed ‘Australia’s Little Cornwall’, in South Australia.

The outbreak of revolution in Europe in 1848 led to a collapse in mineral prices, mine closures and widespread unemployment in Cornwall. Added to this was the misery caused by potato blight. As the potato harvest failed, tenants who relied on this as a cash crop were unable to pay their rent and were evicted from their smallholdings. Enclosure acts and the amalgamation of smallholdings by landlords made things worse, as access to land for producing food, grazing livestock and gathering fuel to supplement mine wages was becoming more difficult. All of these factors fuelled Cornish mining migration. Going overseas to work began to change from being an advancement strategy to one of necessity, or survival.

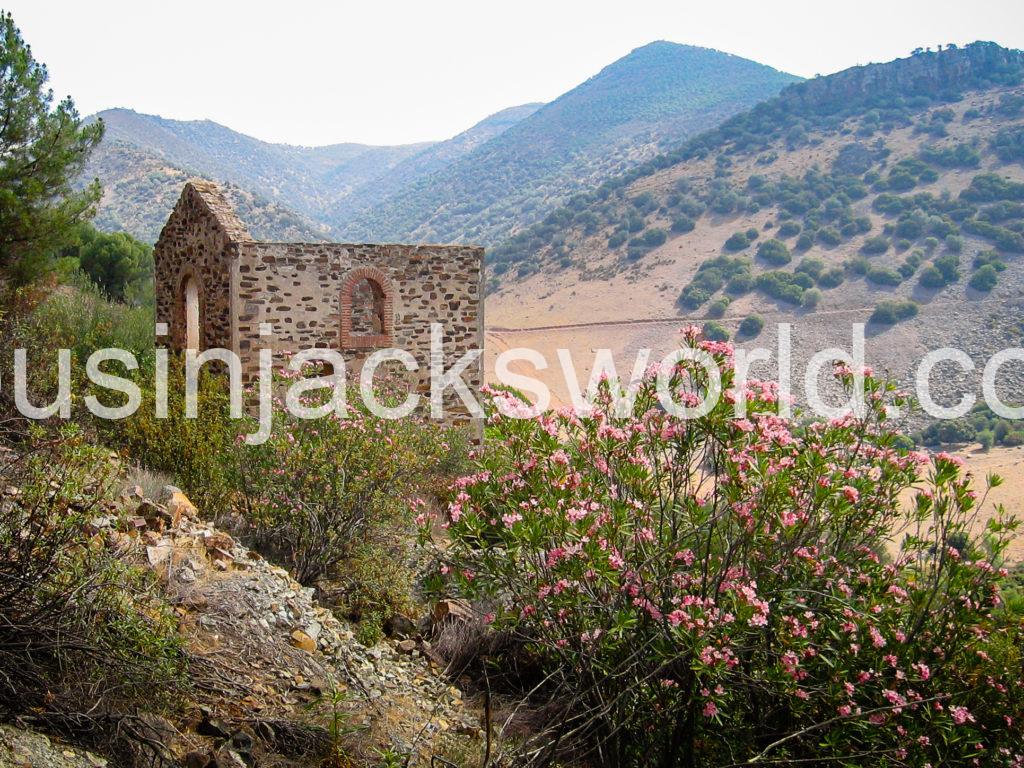

By the 1860s, mineral strikes were underway right across North America, drawing our miners to the Comstock silver mines, the gold mines of Colorado and the rich copper mines of Ontario, Michigan, and Montana. In southern Africa, Cornishmen were mining copper in Namaqualand, and diamonds in Kimberley. Throughout Britain there was scarcely a mine without its Cornish ‘Mining Captain’, and the iron mines of North West England became a magnet for Cornish labour. Across the Irish Sea, mining entrepreneurs, the Williams of Scorrier, were making a fortune from their Wicklow copper and pyrites mines and ‘Cousin Jack’ could be found throughout Europe: from copper mines deep inside Norway’s Arctic Circle, to the lead mines of Linares in sun-parched Andalusia, Spain, home to scores of Cornish-type engine houses.

The Collapse of Cornish Copper and the Rise of Remittances

Economic hard times returned to Cornwall with a vengeance in the mid-1860s, as many famous old copper mines closed following the financial shock-wave caused by the collapse of bankers, Overend and Gurney in 1866. But the writing had been on the wall for years. Cornish mining was lagging behind its competitors. Mining ever-deepening and lower quality ore deposits through crooked shafts with cumbersome pitwork meant that productivity levels were falling. Moreover, a glut of rich copper ore from shallower and less expensive to exploit deposits in Australia, Cuba and Chile, had driven down the market value of ore. This had already pushed many Cornish copper mines to the brink.

Things would have been considerably worse in Cornwall had our towns and villages not been linked to overseas mining communities connected by migration chains forged by the ‘Cousin Jack’ network, and social linkages within Methodism and Freemasonry. This gave employment opportunities not just to mineworkers, but also to those who serviced these burgeoning new mining settlements. People left Cornwall in droves.

Cornish tin mining rallied in the early-1870s, during which time the old copper mining town of Redruth began to reinvent itself as Cornwall’s business and financial hub and a residential centre for ‘new money’. Neighbouring Camborne rose to prominence as the tin mining and engineering capital of Cornwall as the Cornish mining industry contracted to a nucleus of activity centred on the Camborne-Redruth area, with outliers at St Just and St Agnes.

But this was only a temporary reprieve from the inevitable downward spiral of Cornish mining following the development of extensive tin deposits in Australia, the Malay Peninsula, and Bolivia. Many of these could be exploited using opencast methods with cheaper labour, conferring a clear advantage over the mining of Cornwall’s far deeper tin deposits.

Some of the wealth on display in our mining communities in the closing decades of the 1800s came from overseas investments and remittances flooding home from US mining camps, Western Australia, the Kolar Gold Field in India, the Gold Coast in West Africa, and the tin mines of Malaya. Cornish stockbrokers had large investments in the Malay Peninsula, and Redruth was rivalled only by London in terms of raising share capital for the Malay tin mining industry.

But it was South Africa which provided the lion’s share of remittances in the two decades before WW1. Cheaper and speedier passages by rail to English ports and steamer to Cape Town, meant that thousands of ‘Birds of Passage’ could commute to and from the gold mines ‘on the Rand’ (Transvaal). In the Transvaal, wages were higher, even if the cost to miners’ health was high due to the devastating lung disease, phthisis. This was caused by boring into the hard quartz reef with compressed air drills that became known as ‘widow makers’.

People rushed to the post offices of their local towns and villages to cash their remittance cheques after the weekly South Africa Mail arrived, and the tills rang loudly as businesses did a roaring trade. Some families had never had it so good and spent as never before, widening the income gap with non-migrant families who stoically resorted to ‘getting by and making do’. ‘We’re living on South Africa,’ sounded a Redruth newspaper. Indeed, South Africa was viewed almost as the parish next door.

Post WWI Decline in Cornish Mining Migration

But this was not to last. World War One marked a watershed. Many of our countrymen were conscripted only to perish in the trenches of Europe, sundering those migration networks that had long been the lifeblood of Cornwall. Cornish mining engineering was increasingly viewed as outdated and antiquated, its cutting edge long-blunted by emerging industrial giants, the USA and Germany, that were embracing new technologies and machinery.

The decline of British capital and influence on the world stage was matched by America’s ascendancy. In the inter-war period, our highly-skilled, practical ‘rule of thumb’ mineworkers confronted a perfect storm of factors. They were being displaced by progressive working practices that included the decommissioning of steam engines in favour of electrically driven pumps, cyanidation for treating ores, and open cast mining operations.

American capital meant American college-educated managers, engineers and geologists, who hired men from their own country. This left no room for the ‘Cousin Jack’ Mine Captains who had ensured the Cornish domination of the labour market for decades. Finally, men from competing nations who might never have worked in the industry could up-skill quickly using modern machinery.

Cornish mining migration continued, but by World War Two had been reduced from a flood to a trickle. In the decades that followed, a shortage of skilled local miners resulted in men from England, Europe and further afield coming to work in our mines.

A Living Legacy

Today there are estimated to be in excess of six million descendants of those ‘Cousin Jack’ miners and their families worldwide. Cornish societies are thriving in many countries and several overseas mining settlements have twinned with ones in Cornwall. The global influence of our Cornish mining culture, in the shape of Cornish-type engine houses, chapels, houses, and gravestones is evident. It is also recognisable in place names and surnames, cuisine such as pasties, and in music, dialect, folklore and sport.

Our incredible contribution to the global mining industry has been recognised through the inscription of the Cornwall and west Devon mining landscapes as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This highlights the achievements on the world stage of our great little nation, marked as much for our migration, as for our skills in hard rock mining.

My family went to South Africa from Cornwall in about 1897 to stake a claim in Kimberley. I am writing a book about our recent immigration to Canada and am writing chapters about how our family came to South Africa. I have a photo of the layout of the Kimberley Big Hole, showing where the two James claims were.