The Mountain that Eats Men:

A Visit to John Penberthy’s Potosí

In April 2013, I visited the famous mining area of Cerro Rico above the UNESCO-inscribed city of Potosí on the Bolivian Altiplano, on the trail of Cornish mining engineer, Captain John Penberthy (1839-1914). I had a remarkable opportunity to explore some mine workings that had changed little since his time there in the early 1890s.

© Dr Sharron P. Schwartz

I can scarcely believe my eyes when I peer into the gloom of the small store before me. Amid the clutter on the floor are several plastic bags marked ‘ANFO’ which are bulging with light pink grains. ‘That’s ammonium nitrate!’ I whisper to Martin, who then points out an open box containing sticks of dynamite. We block the doorway staring in wild-eyed bewilderment at one of just scores of potential tinder boxes in this narrow street. ‘Go inside’, smiled Roberto, our guide, ‘you have to buy some gifts to give to the miners we will meet on our tour’.

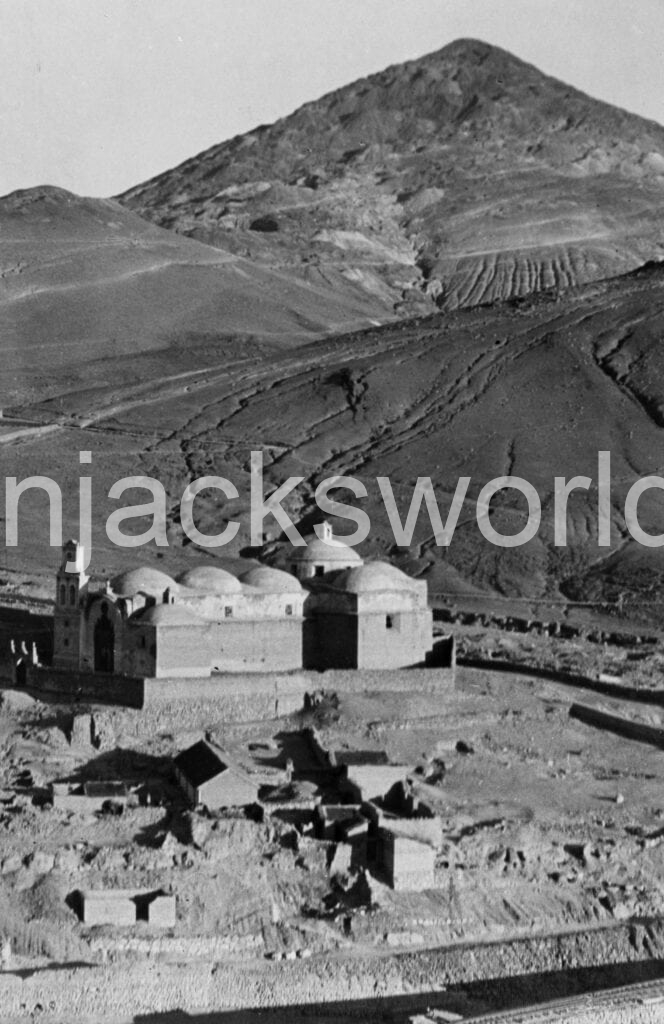

It’s April 2013, and Martin and I are in the city of Potosí, a UNESCO-inscribed World Heritage Site (WHS) at the southern end of the Bolivian Altiplano. It’s impossible not to notice Cerro Rico (Rich Mountain) which looms large over the narrow-cobbled streets of the city. Some 4,090 metres in height, it has given birth to the highest mining city in the world. The silver lodes of Cerro Rico were worked in Pre-Incan times, but were exploited on a grand scale by the Spanish Conquistadores, making the mines of Potosí world famous.

Indeed, novelist, Miguel de Cervantes, placed the words ‘Vale un Potosí’ (It is worth a Potosí), into the mouth of his hero, Don Quixote. The ore derived from these mines bankrolled the Hapsburg Empire for centuries, exciting the envy and suspicion of all other monarchs in Europe. It was said that you could have built a bridge of silver ingots from Potosí to Madrid from the ore mined there.

But this incredible wealth came at a huge cost to human life. Cerro Rico can be seen as a colossal monument to the tragedy of Spanish conquest. Potosí boasts a number of ornate Baroque churches, a virtually intact mint and opulent colonial buildings all raised on the back of slave labour, and was formerly described as ‘a monstrous Babylon’. Some say this city and its mountain represent the largest site of physical exploitation in the world during the colonial period (1546-1825).

Countless indigenous men from across the Andes were press-ganged by the Spanish into servitude to work the mines under the Pre-Colombian mita system. Alongside black African slaves, the miteros toiled in the most appalling and dangerous conditions, often sleeping underground for weeks on end. Many never saw their homes or families again, killed in the mines, literally worked to death or poisoned by the toxic effects of mercury used on the patio (ore processing) floors. Although records of fatalities were not kept, it is estimated that over eight million mineworkers perished in Potosí during colonial times. Never mind a bridge of silver to Madrid, there were enough hapless victims to build a road of bones from Cerro Rico, ‘the mountain that eats men’, all the way there too.

By the early nineteenth century, the output of the Cerro de Potosí began to significantly decline as the silver deposits worked in the rich oxidised zones in the upper part of the mountain were mostly worked out. Compounded by looting during the 1820s Wars of Independence, Potosí’s star began to wane. However, deeper tin lodes (along with other base minerals such as zinc, lead and cadmium) gradually supplanted silver during the turn of the twentieth century.

By the 1930’s, the tin barons who controlled the majority of Bolivian mines were perceived to be exploiting the indigenous labour force. Groups of workers banded together to fight for more autonomy, and the tin barons were eventually marginalized when the mining sector was nationalised and the Bolivian Mining Corporation (COMIBOL), was formed after the revolution of 1952.

The collapse of the tin market in 1985 resulted in massive layoffs of miners and considerable restructuring of the mining sector, including the decentralisation of COMIBOL into five semiautonomous and privatised mining enterprises in 1986. In order to survive in this hostile climate, the miners formed cooperatives which are still functioning today.

COMIBOL still owns Cerro Rico, but licenses its operation to a handful of multinationals and over 200 such cooperatives, who pay to rent an area of the mountain in which they have been granted permission to work, sharing the profits of their labour between themselves. The rise in mineral prices in recent years has witnessed a recovery and expansion of the mining sector. Over 16,000 miners are presently estimated to be at work in the mines of Potosí, most working in cooperatives primarily extracting low grade silver bearing ore from the old workings in Cerro Rico, which is becoming dangerously unstable…

Cornish Connections

It was not just Potosí’s rich colonial past that drew me here, for I knew that the Cornish worked at mines in this area, and that it was the onetime residence of the redoubtable Captain John Penberthy (1839-1914), the former resident mining manager at the Huanchaca Mines in Pulacayo. I have been researching him for years with the objective of writing his biography, and have been travelling through the mining camps of the Altiplano on his trail for weeks.

Some of his countrymen were employed by the Royal Silver Mines of Potosí (Bolivia) Ltd., an English concern set up in 1884, which operated until 1896. This company boasted mining and dressing machinery imported from England to work the low-grade silver ores known as pacos.

There were never large numbers of Cornishmen in Bolivia, and Potosí acted as a magnet for those working in the remote mining camps of the Department of Potosí, while the Tarapaya Hot Springs, some 20km north of the city, which were believed to have had curative properties, attracted those struggling with various ailments in the forbidding high altitude climate of the Altiplano. The favourite haunt of the Cornishmen during Penberthy’s day was the French Hotel. He had this to say of the city:

It at one time contained 100,000 inhabitants, but like all towns whose existence depends on the prosperity of the mining industry, is now in a state of decay. There are probably not more than 10,000 inhabitants, more than one half of the houses are roofless, many of the mills used in the good old days are in ruins, and the inhabited portion of the city seems every year to cover a smaller area. There are some very fine churches and a good mint to be seen. The climate is cold, but healthy, the air wonderfully pure and bracing… The commerce seems to be in the hands chiefly of the Spaniards, and the foreign element is not strong in Potosi, or any other part of the Republic. Potosi mountain was found to be rich in minerals in the year 1545, since when it has yielded more riches than any other piece of ground of an equal area in the world. The hill, looked at from the east, is in the form of perfect cone, and its height is about 3,107 feet above the level of the principal square of the city.

Intrigued by the history of this famous mining area, and keen to imitate Penberthy’s insatiable curiosity, sense of adventure and boundless courage, for a mere US $10, Martin and I have signed up for a half day tour into Mina Candelaria (the Candlemas Mine named for the famous Catholic fiesta in February). Kitted out with well-worn protective overalls, a helmet, battery powered cap lamp, wellies and colourful bandanas, we hop aboard a minibus with several other people.

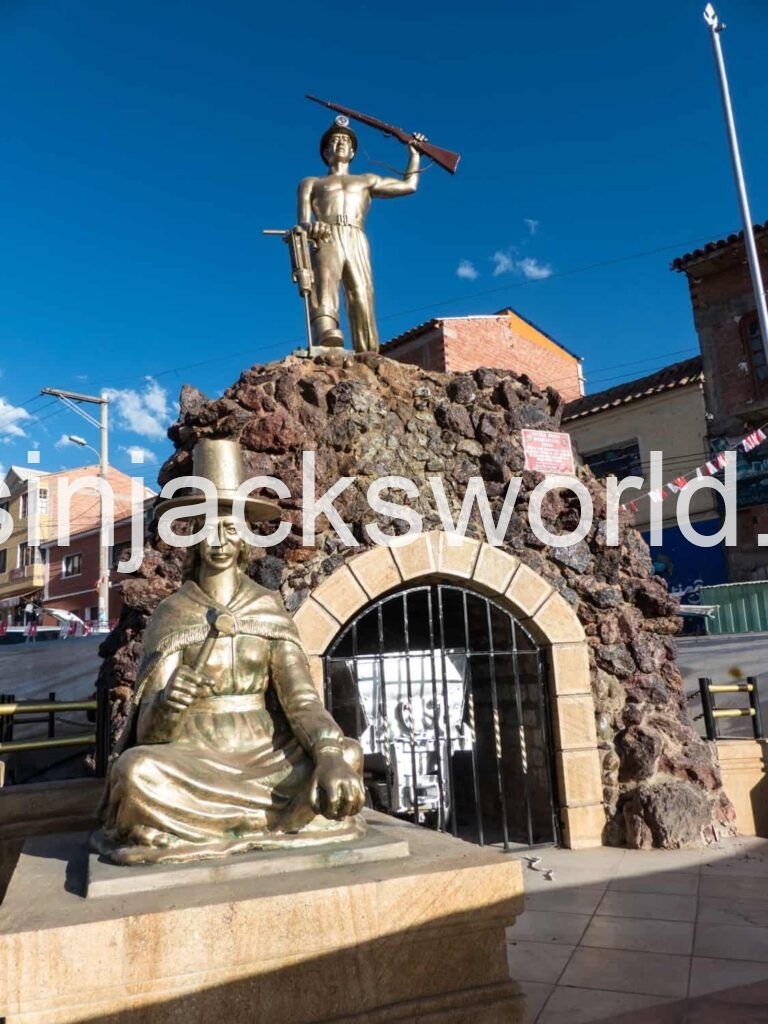

This sluggishly groans up a maze of narrow streets spewing clouds of black fumes, before entering the bustling Plaza del Minero (Miner Square) where it shudders to a halt. At its centre is a huge rocky mound at the base of which is a grilled adit entrance with a mine wagon behind it. Atop this mound, supposedly meant to represent Cerro Rico, is a gleaming golden figure of a miner holding a pneumatic drill in one hand and a gun aloft in the other. It speaks volumes about Bolivian history, and would certainly have drawn a wry smile from Capitán Penberthy!

My eye then catches another resplendent figure kneeling below, a chola woman, complete with characteristic full skirts and bowler hat brandishing a small hammer in her right hand and a rock in her left. She is one of the palliris, female ore-breakers who fossick through the mine dumps of Cerro Rico to grub an informal living to help to maintain their families. Female ore-dressers were common sights on Bolivian mines, including at Huanchaca which John formerly managed. They were expert at sorting the ores, and as skilled at stealing it right from under the eye of the overseer, as the miners were at smuggling it out from underground! As John remarked sardonically in 1895:

Ore stealing from the mines is quite the proper thing to do, and is winked at by the governing authorities. The miners, many of them, would rather work without pay in a rich mine than receive a good day’s pay for working in a poor mine. The only thing to do is to take all the care that is possible, and after that if the robbing still goes on one must say nothing about it and take still more care.

Although it has been a WHS since 1985, to suggest that Potosí possesses a charm comparable to other WHS cities in the Andes is stretching the imagination somewhat. As John Penberthy noted, the climate is cold; indeed, it is bitterly cold at night, and the altitude means you fight for every breath walking up its steep cobbled streets. He noted that the air was wonderfully pure and bracing. Well not anymore! You are choked by sooty clouds of cheap petrol fumes from the incessant traffic and the unavoidable inhalation of the beige haze of fine mineral dust that seems to seep into every nook and cranny. Many parts of the city are gritty working neighbourhoods and numerous buildings in the historic centre look decidedly down at heel; an atmosphere of quiet neglect appears to have settled over the streets along with the fuel soot and mineral dust.

The Miners’ Market which runs higgledy–piggledy up the steep side of Cerro Rico which is thronged with squatting vendors hawking goods from hand carts and fast-food stalls feeding ravenous groups of miners just off-shift, definitely falls into this category! It is in one of the small stores here where we spot the dynamite and ANFO for sale. We find it hard to believe that high explosives are stored so casually in the scores of shops lining this street and are sold to anyone, no licence required, no questions asked. Along with bottles of water and fizzy drinks, we do as Roberto suggests and purchase two explosive kits, each containing a small plastic bag of ANFO, a stick of dynamite, and a coil of safety fuse, for the princely sum of 17 Bolivianos (about 1.50 euro) each!

Almost opposite the mining store, next to a chola woman busily hacking the head off an alpaca’s carcass, is the stall of a coca leaf seller. Prematurely aged, the harshness of life on the Altiplano is etched into the thousands of lines on her brown and wizened face. Roberto explains that the miners do not eat underground, but rely on the stimulating effects of chewing coca leaves to dull their hunger and stave off fatigue during their arduous 10 hour plus shifts. ‘First explosives, now drugs!’ I muse, as we hand over the money for a couple of bags of the pale green, strong smelling leaves, drawing an almost toothless smile from the vendor. Miners have used coca leaves as a stimulant for centuries, and they were mentioned among a list of essential items which included fuel, salt and corn that were regularly transported to the Huanchaca Mine which John managed from 1874 to 1882.

The Rape of ‘Mother Earth’

After a short journey out of the city we stop outside a series of crude hutches above one of around 39 ore treatment plants that dot the mountainside. In these hutches, a cooperative’s ore is stored and assayed before being processed so the group can receive its fair share of the price of the concentrate. The mill is truly primitive and the workers wear no protective equipment. Roberto explains that the ore is processed with various chemicals and reagents to separate the silver, casually waving his hand at an open vat of cyanide nearby: ‘it used to be worse when mercury was used!’ Several of our tour group look horrified and promptly cover their faces with their bandanas! The ore is reduced in ball mills then treated in froth flotation cells.

Base minerals occurring with the silver ore, such as lead and zinc, were previously discarded as it was not considered commercially viable to extract them. The reworking of the dumps around Cerro Rico is nothing new, as John observed with regard to the ‘pacos’ in the early 1890s. Today, rising mineral prices have resulted in an increased recovery of all minerals. We suspect that the untreated effluent from this mill eventually discharges into a local river system…

Behind the processing plant, Cerro Rico rises against the deep blue sky of the Altiplano like a giant ochre-coloured anthill. It contains more than 650 separate entrances and is literally honeycombed with hundreds of thousands of tunnels that follow increasingly impoverished mineral veins. With limited state regulation and little concern for safety, the mine workings are randomly driven and the whole mountain is now believed to be inherently unsafe; catastrophic collapses are predicted.

Indeed, all mining near the peak was suspended in 2009 after the ground there began to subside. Over 500 years of mineral extraction has already decreased the mountain’s height significantly. This epitomises the rape of ‘Mother Earth’ and on a grand scale, for in indigenous Andean culture, Cerro Rico is adjudged to be female and mountains represent Pachamama, ‘the Mother Earth’. This fact was quickly understood by the conquering Spaniards who ensured that she became synonymous with the Virgin Mary to convert the indigenous peoples to Catholicism. This association is especially evident in the anonymous painting of the Virgin of the Cerro Rico of Potosí (1720) on display in the Royal Mint mentioned by John Penberthy. In this image, the Virgin Mary emerges from the mountain which some scholars argue merges her with the Andean mother earth deity, Pachamama.

Cooperative mineworkers can earn three to five times the amount of money made by those in menial service jobs or agriculture, although by western standards their wages are still pitifully low. Moreover, they are not immune to exploitation, and many complain that the managers take the lion’s share of the collective income leaving them with barely enough money to get by on each month. But with Potosí being the poorest state in the poorest country in South America, mining is the area’s lifeblood. The costs to human health or the environment are far outweighed by the driving need to feed large families. More than half of the 240,000 residents residing in the city whose dusty houses creep towards the mountainside as if lured to Cerro Rico by an invisible magnetic force, depend directly on the mines for their livelihoods. It is not hard to see why Potosinos have good reason to thank Pachamama, making daily libations to her for the gifts she has bestowed on Cerro Rico…

Mina Candelaria

Our minibus continues ever higher up the mountainside, lurching over rutted tracks and throwing up clouds of ochre coloured dust, eventually arriving outside the entrance to Mina Candelaria which is over 4,500 metres above sea level. I was struck by the well-built entrance portal to the adit. This was not surprising in the least. John Penberthy marvelled at the skill of the Bolivian pongos, who secured bad and running ground and constructed stullwork from stone to shore up dangerous sections in the mines in lieu of timber, which was scarce in Bolivia.

Possessing four levels and running continuously for over 300 years, Mina Candelaria is one of the oldest mines in the Cerro. Crudely built stone buildings half set in the ground with roofs of galvanized iron and plastic sheeting held down by rocks and bits of old machinery, cluster around the mine’s main portal. An empty wagon rumbles by on a tramway to the entrance portal, pushed by a short, but powerfully built miner who disappears into the darkness of Level One. We follow him in to begin our two-hour tour. I am now literally following in the footsteps of Captain John Penberthy who explored many of these old mines in the early 1890s.

The portal walls are initially coated in fine dust, but as we progress deeper into the mine, blooms of bright yellow sulphur appear on everything. Several miners pass us on the way in to start their shift. Roberto knows them all; he had once worked here as a miner himself. Bent double in places, the high altitude immediately begins to take its toll and it becomes harder to breathe as the temperature inside the level rises uncomfortably.

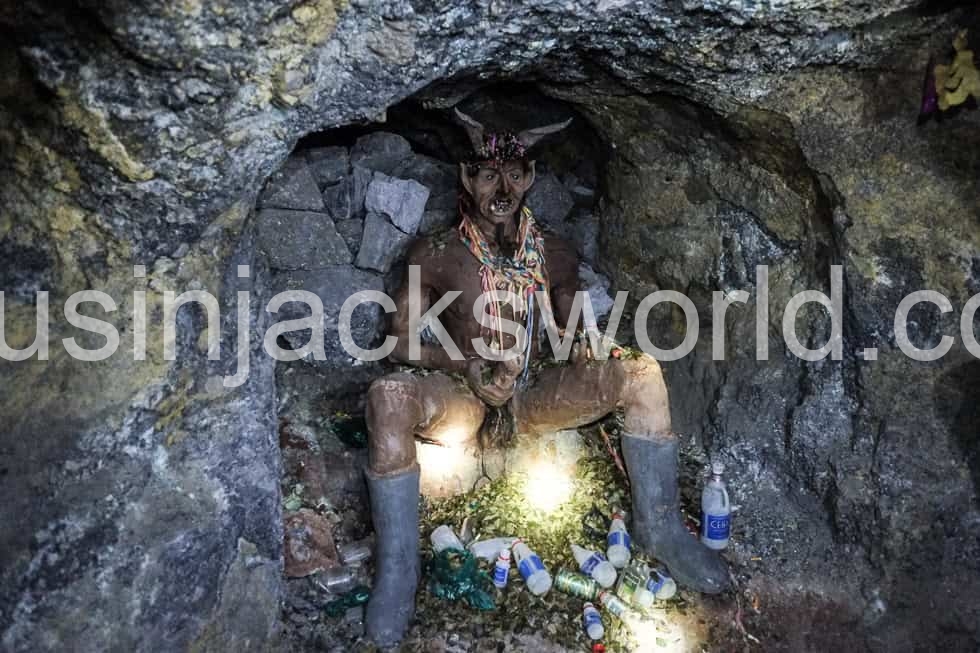

About 400 metres in and close to an ore chute encrusted with sulphur, we stop. Roberto announces that we are going to clamber on our hands and knees over a pile of loose rock to access a short, low drive beyond. Two of our group instantly announce that they are too afraid to continue and head back down the tunnel to the surface. Inside the hot, airless drive, gasping for breath and seeking somewhere to sit, I stagger about like a drunkard. I am suddenly aware of a figure close to me. As I turn my head, my cap lamp illuminates a hideously grotesque horned and moustached clay figure sporting an enormous erect phallus. It is seated amid a heap of empty tin cans, plastic bottles containing ‘aguardiente’ and crumbling cigarettes, garlanded in luridly coloured paper streamers and covered in rotting coca leaves.

‘Meet El Tío, the Lord of the Underworld!’, announces Roberto. Just as local people make daily libations to Pachamama, the miners make offerings each Friday to El Tío (literally ‘The Uncle’), who is associated with pre-Hispanic huacas (revered objects) as well as the Christian Devil. He is a central figure in the ritual life of Bolivian mining communities. Interestingly, John Penberthy makes no mention to El Tío in his reminiscences and neither do any of his contemporaries.

By the late nineteenth century, it seems as if the ancient belief of perceiving the mountains to be sacred spaces which had to be ritually respected had been overlaid and fused with elements of Catholic worship. However, a prominent French writer remarked that although the descendants of the Incas (the Quechuans) were Christian fanatics, he was told by a Bolivian that they kept the spirit of times past under their new faith: ‘The local beliefs have survived, and far from defeating them, our priests protect them and consolidate them.’ This was something that greatly aggravated John Penberthy, who had no time for the Catholic faith. Indeed, his clamping down on the time wasting involved in myriad daily rituals at the Huanchaca Mine almost led to his assassination in 1874! I wonder what he would have to say now that Amerindian beliefs have once again come to the fore as Bolivia has undergone an awakening and resurgence in its indigenous identity and customs? I think I can well imagine…

As there is no state enforced health and safety regimen in the mines of Cerro Rico, and cost cutting by the cooperatives sees little attempt to shore up tunnels or replace failing timberwork, the miners place their faith in Tío, presenting him with gifts of alcohol, coca leaves, cigarettes and llama blood in return for his goodwill and guarantee of health, safety and good fortune in the mines. Judging by the state of the level we have just traversed, despite what John Penberthy might have thought, I half wish I had brought along something to placate Tío myself!

Returning to the tunnel on Level One, we then began the hellish descent down through ancient workings via Level Two to Level Three. Used nowadays only as an access route for the levels above and below, the air in Level Two is foul and thick with dust. The way on involves crawling on all fours in places under rotting stulls holding up large quantities of deads and through tunnels barely large enough to permit an adult to pass. Squeezing through partially collapsed raises and shimmying down dodgy stull-work within a winze which bottoms out dangerously close to an open stope, are indelibly etched on my memory. Standing next to an old windlass above this winze, Roberto explains that before an electrical winch was installed a few years ago to raise the ore from Level Three to Level One, the miners had to carry over 40 kg of ore up through these tight rocky passageways in bags slung over their backs.

By now my face is beaded with perspiration and my heart thumps incessantly against my ribcage as I fight for every breath in the impossibly hot, dry and foul air. The acrid sulphurous taste of the dust catches in the back of my throat and makes me cough till I gag. ‘I’ve been in safer abandoned mines in Cornwall,’ I say to Martin, as we clamber down another horrible raise, only to arrive on a narrow rocky shelf where I light-headedly gaze into a deep stope that promptly swallows the light from my cap lamp. One slip here…

It is with considerable relief that we finally emerge into a tunnel in which it is possible to stand upright. ‘This is Level Three, the “Gringo Level”’, Roberto says with a laugh. A low hiss from ventilation pipes bringing clean air down from the surface fills the tunnel. It is now far easier to breathe. This is the main haulage way where ore from Level Four is raised and trammed along in wagons to be sorted before being hauled to the surface. We follow the tram tracks for some distance before ascending a short ladderway into a rock-strewn drive. A hammering sound greets us and in the gloom a miner appears at the forehead.

Alone in this airless drive, one cheek bulging with a wad of coca leaves and drenched in perspiration, he is single jacking a bore hole with a drill steel for an explosive charge. It is a scene with which John Penberthy would have been familiar in the 1890s. I confess to being moved as I shake this man’s hand and give him our gifts of explosives and coca leaves.

We then return to the main haulage way where several men pass us, straining to push heavily laden wagons of ore which constantly jump the tracks. Some don’t look old enough to shave. They are conveying the ore to their colleagues who are shovelling it into rubber kibbles to be hauled up a shaft by the electric winch. Most are working, red eyed, amid clouds of choking dust without masks. It unsettles me to think that these young men, who stop work to greet us and humbly accept our gifts of coca leaves, fizzy drinks and water, are unlikely to reach middle age. Indeed, life has ever been this way in Bolivian mining areas. Of the Bolivian miner, John Penberthy had this to say in 1895:

But a result of bad systems, ill-treatment, liquor, a total disregard of the laws of health, and kindred vices, he is degenerating… Generally speaking, they receive their money in advance, the truck system is rampant, with the result that the miner is ever in debt, loses his self-reliance, self-esteem, and dignity, and is little better than a slave seeing that he serve no other master until the debt has been paid off. An old miner is a ‘rara avis’ in Bolivia. He starts to act like a man while still a boy, drinks all he can, lives badly as a rule, and at thirty years of age is an old man.

We are not taken to Level Four, currently the main work area, where the horrors of the working conditions may be left to the imagination. The climb back up through the old men’s workings of Level Two is even more arduous, stifling and airless than the descent, and I am mightily relieved to see the bright pin point of light of the entrance portal appear in the reeking sulphurous darkness.

Cerro Rico is no model of operational safety and its mineworkers toil in shocking conditions that lag way behind the rest of the world. And this mountain is still eating men. On average, life expectancy among the miners is less than forty years and several men die each week from silicosis or through mining related accidents. Countless women in Potosí are widows or widows in waiting, and most face an uncertain future of bringing up large families on their own. Again, nothing new here, for John Penberthy recalled that he knew a woman in the mining town of Machacamarca, south of Oruro, who had been married fourteen times and was, when he last saw her, waiting to accept the next offer.

However, it might be somewhat disingenuous to see these men and their families purely as victims. They value their independence, are proud of their work in the mines, and receive better pay for their efforts than they could obtain if employed in menial jobs outside the mining sector. Although he got off on the wrong foot in Bolivia with the indigenous miners which almost cost him his life, John Penberthy came to have a deep respect for them:

The Bolivian miner is good workman, and when treated fairly and justly is a hard-working, long-suffering man, and will compare favourably with the miners of any other country.

I do, however, question the wisdom of allowing hundreds of tourists each day to enter workings that are unregulated, inherently unsafe and, quite frankly, a death trap. I can very easily imagine the choice words Capitán Penberthy would have uttered!

Given that the current high price of minerals has stimulated mining activity and the fact that the whole of Cerro Rico has been rendered so fragile and unstable because it is literally riddled with mine workings, ‘the mountain that eats men’ could soon find itself feasting on unsuspecting tourists.

The Mountain that Eats Men: A Visit to John Penberthy’s Potosí

Dr. Sharron Schwartz

Specialist in Cornish Mining Migration and transnational communities

Pingback: A Cornishman in Chilecito, Argentina - Cousin Jacks World

I was doing a bit of genealogy today and found a few Cornish who were in Bolivia. Thus far I don’t know who Mr. KEMP the father was or the mother, more research to do. However I have the following KEMP children born in Bolivia:

William – 1900 not sure if he was born in Bolivia, but in England he was listed as either William or Guillermo. On his WW1 papers he was Guillermo. Sadly he died at just aged 19.

Samuel – 1902 Beni, Bolivia (as listed on the 1921 census for Truro)

John – 1903 Beni, Boliva

Harriett – 1907 Beni, Bolivia

Catherine – 1910 Santa Cruz, Bolivia

Lola – 1914 Para, Brazil

The family was back in Cornwall in Truro by 1921, well the children were. They were all living with Williams young widow aged just 19 with her 2 babies as well as William’s 82 year old grandmother!

I will update as I find more.

If you run across any KEMPs in Bolivia I would like the information.

Oll an gwella,

Jim

Sorry I had not seen your message earlier; I have been away on a research trip to Mexico and the US.

Here’s what I know about the Kemp family of St Day and Bolivia.

William Kemp, a (mine) blacksmith form Pink Moors, St Day, married Catherine Mitchell from Vogue at St Day on 22 June 1861. He was aged 26 and the son of miner, Samuel Kemp. Catherine, aged 21, was the daughter of miner, John Mitchell.

On the 1871 Census, Catherine is shown living at Vogue near the Star Inn with her daughter and mother, Mary Mitchell, a 59-year-old widow. Catherine has a 7-year-old son named Samuel. William Kemp is not enumerated with them. The family is obviously struggling financially, as Mary is described as a pauper and Catherine is working as a charwoman.

Samuel was born in 1864 (June quarter, Redruth RD). The transcription for his baptism seems incorrect, stating he was baptised in the Primitive Methodist circuit at St Day in June 1863. This must surely be 1864. His family were then living at Salem in Kenwyn.

A daughter named Elizabeth Jane was born in the March quarter of 1865. She was baptised on 27 March in the St Day Primitive Methodist Circuit. The family was then resident at Chacewater, Kenwyn, where William was noted as a blacksmith.

William seems to have migrated sometime between 1864/5 and 1871, and his wife and children went to live with her mother at Vogue. Elizabeth Jane died at Vogue aged three years nine months old on 2 October 1868 (Royal Cornwall Gazette, 8 October 1868). She was buried at St Day. The family are not on the 1881 census as far as I can tell, so they had probably migrated to join William. It seems likely that he had gone to Bolivia, given that his family were later definitely there.

Where William went cannot be nailed down with any certainty, but there was a ‘Mr Kemp’ associated with the silver smelting works at Huanchaca, Bolivia, in 1883. This mine was the largest and most important silver-producer in the Americas and had been managed by Cornishman, Captain John Penberthy (I am currently writing his biography), for the previous eight years. This might be William, as there were so few Cornishmen in Bolivia at this time.

In the West Briton of 11 May 1916, it states that Mr William Kemp of Baldhu died at the Redruth Hospital of an intestinal complication. Moreover, it adds that he had returned to Cornwall from Bolivia with his aged mother, wife and large family some two years previously. I believe this to be a newspaper error. The man who died was actually Samuel, hence he returned with his wife, aged mother (Catherine) and large family. Indeed, the civil register records Samuel’s death in the Redruth RD aged 63 June quarter, and he was buried at Baldhu on 10 May 1916, with the parish register noting he died at the Miners Hospital Redruth.

In September 1916, Magdelena Kemp, aged 37, was buried at Baldhu. She was undoubtedly Samuel’s South American-born wife. It seems her maiden name was Urdininea. Their daughter Catalina was born on the 9 January 1910 and baptised at the Inmaculada Concepción, Concepción, Santa Cruz, Bolivia on 14 July 1911.

Catherine died aged 87 in 1927 in the Truro RD. I imagine that William Kemp died out in Bolivia. But it’s hard to get quality information about the whereabouts and fate of Cornishmen in the country, as mining company records have not survived, the newspapers have not been digitised, rites of life records are sketchy to say the least and there was no British consular presence in the country ensuring that records were maintained. The only one I could find of the family in Bolivia was that of Catalina’s baptism. I am still looking for records on Penberthy after around 30 years!

Hope this is helpful! Good luck with the research and if I come across anything more of interest, I’ll give you a shout.