São Domingos, Portugal

Unless otherwise stated, all content is © Sharron P. Schwartz and may not be reproduced without permission

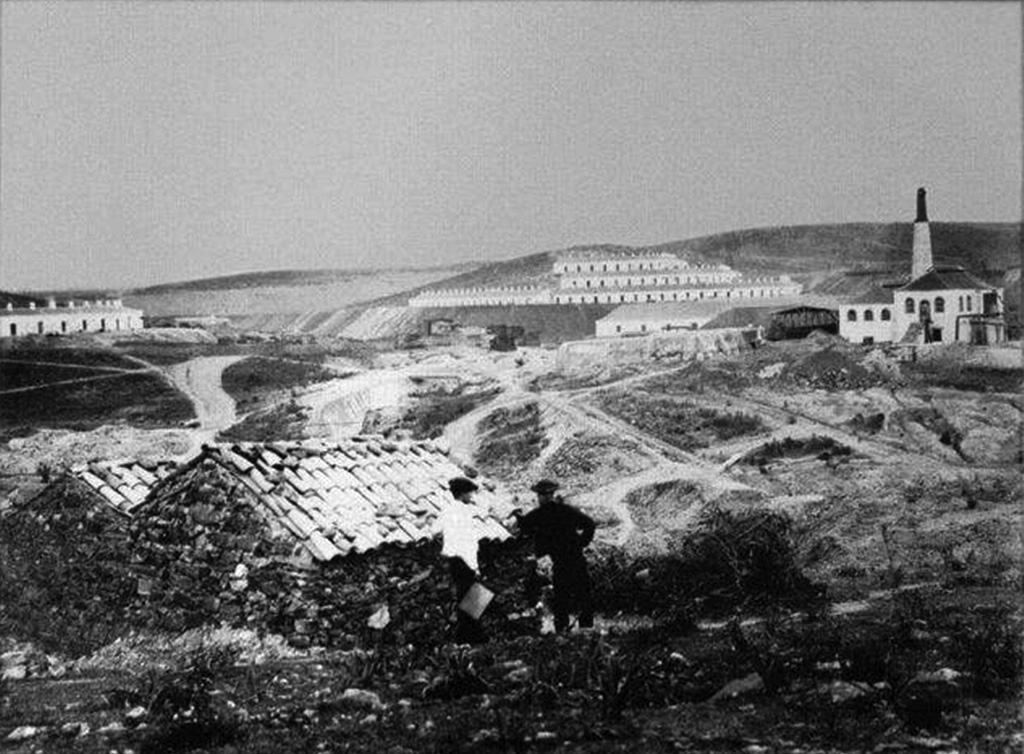

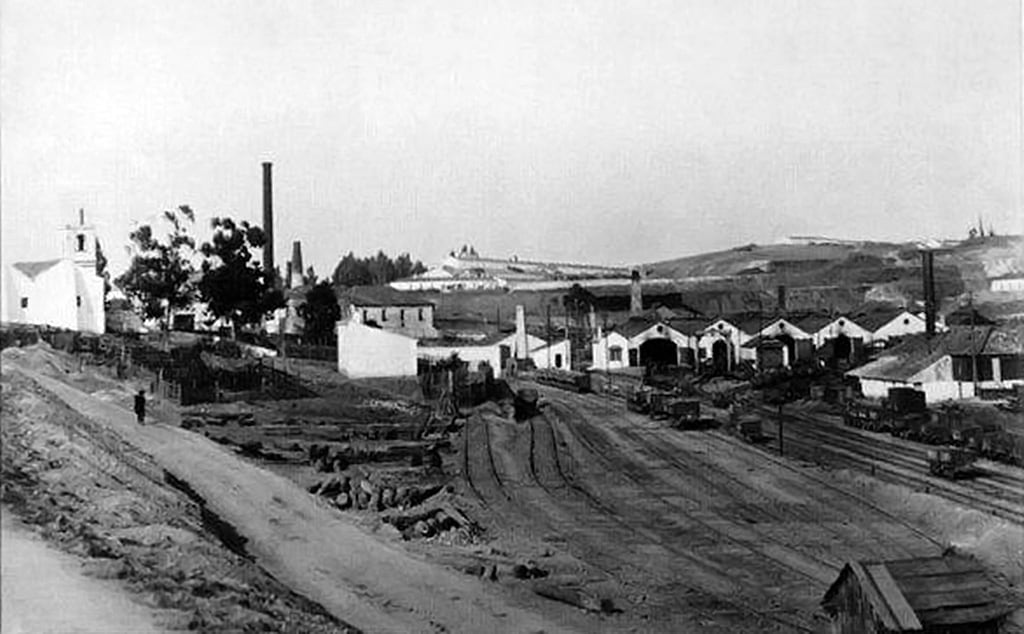

Cornish mineworkers at Mina de São Domingos, in the ‘Iberian Pyrite Belt’

The São Domingos mine is located in a hilly part of south Alentejo about 20km to the east of the nearest large town, Mértola, and is some 3km from the Spanish border. Some 18km to the west is the River Guadiana which, after the port of Pomerão, forms the border with Spain as it flows south into the Atlantic Ocean. The settlement of Mina de São Domingos that served the mine is over 250km to the south east of Lisbon along the A2.

The mine lies on an outcrop of the polymetallic Iberian Pyrite Belt (known in Portuguese as the Faixa Piritosa Ibérica), a geological feature some 30-60km wide located in the southwest part of the Iberian Peninsula, which runs roughly east-west for 300 km from the River Guadalquivir at Seville in Spain, to Águs de Moura in Portugal. This globally significant region held the greatest massive sulphide deposits in the world.

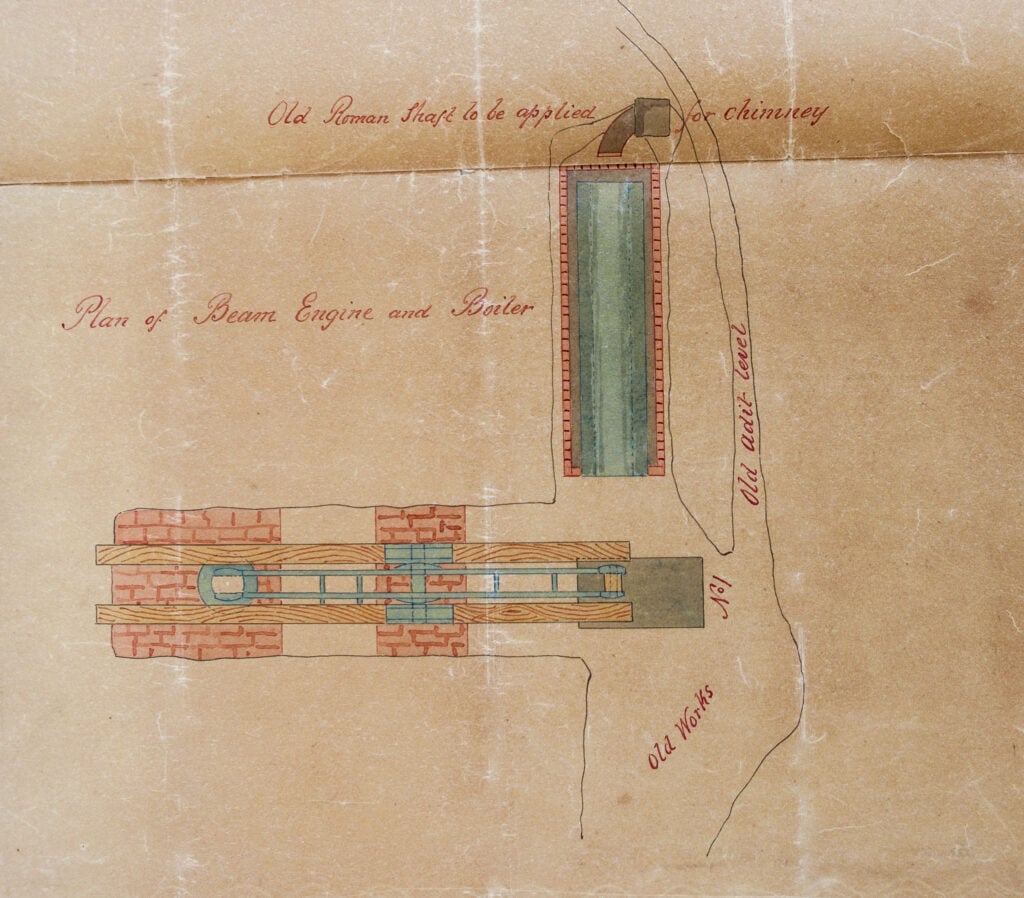

Various mines within it were worked from antiquity for gold, silver and copper, including Rio Tinto, Tharsis and São Domingos. Indeed, a drawing for the installation of an underground beam engine at the ‘Santo Domingos Mine’ dated in 1871 that is archived at Kresen Kernow, Redruth, depicts Roman workings at São Domingos.

It is believed that the mines were wrought to a depth of up to 40 metres, and a waterwheel used in the Roman drainage system was later taken from the workings and is now exhibited in the museum of the École des Mines in Paris. At the International Exhibition in Porto in 1865, a number of Roman coins found in the mine dating from the rule of Tiberius (AD14-37) through to Arcadius (AD395-408) were exhibited, as well as finds from the Islamic period.

The Iberian Pyrite Belt was also among the largest sources of European copper into modern times. From the mid-nineteenth century, they were also the main source of sulphur for the burgeoning British chemical industries.

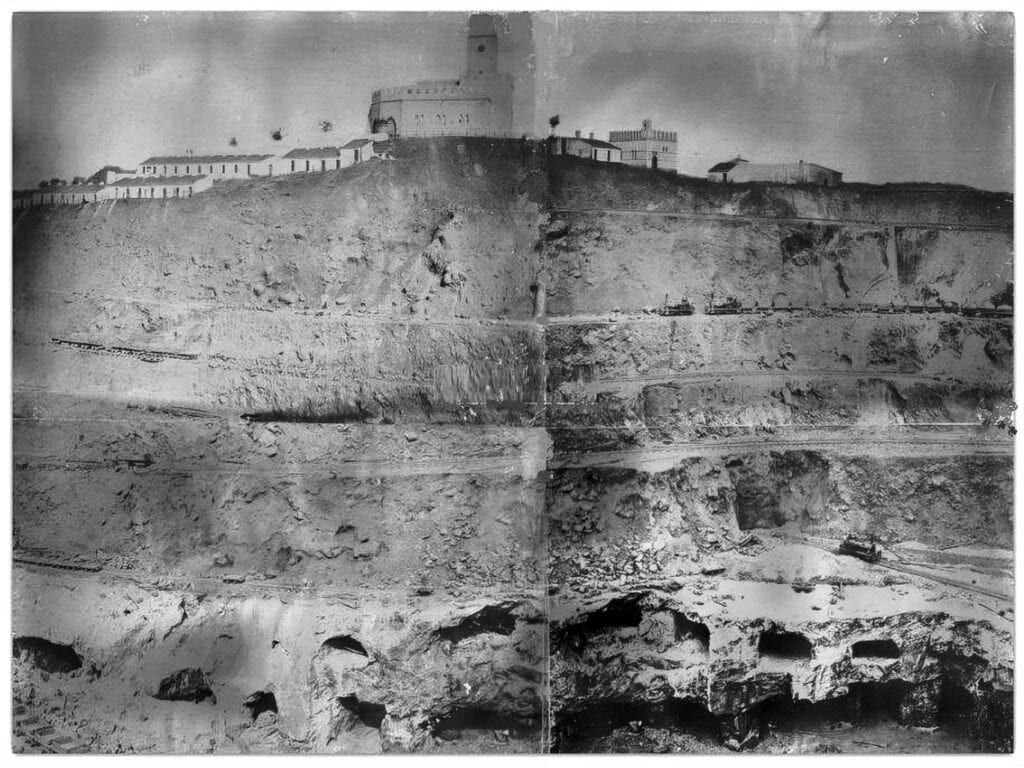

The village of Mina de São Domingos grew up around the mine from the late-1850s to house a workforce that averaged around 3,000. From 1867, the mine was exploited not just by underground levels, but by opencast methods. When it closed in the 1960s, it left a remarkable industrial landscape with an enormous flooded opencast at its heart, as well as a number of surface buildings.

Over its 112-year working life, São Domingos produced about 25 million metric tonnes of copper ore which was primarily sold in Britain. It was without doubt among the most important industrial ventures ever undertaken in Portugal. Today, in common with other mining communities along the Pyrite Belt, the local population struggles to confront a legacy of contamination and acid mine drainage. It is hoped to stem the tide of post-industrial decline through heritage tourism.

Getting There

The mine was opened in a blood red hill surrounded by ancient slag heaps, the detritus of the ore smelting process. Atop the hill was a hermitage to São Domingos (St Dominic). This hermitage was sited in a very wild and remote region of Portugal that has an arid climate and poor soils and was badly served by roads. A road to the nearest large town, Mértola, was not built until the last decade of the nineteenth century.

In 1862, an 18km narrow gauge railway was constructed to link the mine to the River Guadiana and a port, Pomerão, was developed on it from whence the ore was shipped downstream to the Golfo de Cádiz and then to Britain. Migrating miners would have taken ship to Pomerão from British ports such as Bristol or Swansea where the ore was shipped to be sold/smelted, and then travelled by mule along the ore cart road to the mine. Some might have hitched a lift on the railway.

Later travellers could travel from on a river steamer up the Guadiana to Mértola, which took a day. After this they crossed the river by ferry, then took a horse and carriage along the new road built to the mine, which took another day.

The British Development of São Domingos

By the mid-nineteenth century, Britain’s insatiable demand for raw materials to power its industrial revolution, especially with regards to minerals and metals, meant that ore deposits worldwide were being prospected and developed. In Portugal, João Maria Leitão published a series of articles in 1850-51, focusing attention on mineral deposits in the country that had been worked in antiquity.

Interest was piqued, and in 1852 the Portuguese government took a lead from the government of neighbouring Spain, and granted permission for foreign enterprises to exploit Portuguese mineral deposits. French mining engineers had been the first out of the blocks in seeking to develop Spanish mineral properties, and in 1853, French mining engineer Ernest Deligny, the manager at Tharsis in the Iberian Pyrite Belt who was seeking to expand operations from the great Rio Tinto mines, rediscovered ancient workings at Calañas and Vuelta Falsa, close to Tharsis.

In 1854, an Italian named Biava employed as an undermanager at Tharsis, was dispatched by Deligny to search for possible workable deposits on the Portuguese side of the border. Biava found a number of ancient workings which he registered in his own name, two of which were at São Domingos, with the proviso that work had to begin within six months. In 1855, Deligny bought the registration from Biava along with land surrounding the registered concession.

Deligny lost no time in setting up a mining company in Seville named La Sabina, becoming one of its three French directors. On 12 January 1857, the concession to work the São Domingos mine was granted to La Sabina and there were soon 50 Spanish and Piedmontese day-labourers working at the site. However, Deligny found that his duties at Tharsis did not permit him to work two major deposits simultaneously, so in May 1858 he let the mines to British company, Barry and Mason Ltd., for 50 years on a royalty basis, renewable forever.

The managing director and chief mining engineer was Essex-born James Mason (1824-1903), who had been educated at the École des Mines in Paris. Following his graduation in 1848, Mason gained practical experience as the chief mining engineer at a collection of silver-lead and copper mines near Bilbao and Burgos in Northern Spain operated by three interconnected British-owned entities: The Peninsular, Iberian and Castilian Mining Companies. These companies had Cornish involvement in the shape of Calstock-born consultant engineer, Captain Jehu Hitchens of Tavistock, who inspected the various mines on behalf of those companies. Indeed, Mason nurtured links with the Tamar Valley mining area, acquiring shares in Devon Great Consols in 1856. The three companies were unsuccessful and wound up in 1858, with the Peninsular being particularly problematic as it resulted in the lessors taking out a lawsuit against Mason.

Francis Tress Barry, born in 1825 in London, had become Vice Consul for the province of Biscay in Northern Spain at the age of just 21. At 22 he had become Acting Consul for the provinces of Biscay, Santander and Guipuzcoa. The two men had founded Mason and Barry Ltd. in London in 1855, and in 1856 were partners in F.T. Barry and Co, which dealt with the import of industrial goods and machinery from England.

Following the collapse of the trio of mining companies in Northern Spain, Mason had moved south to work for Deligny at the Tharsis and Calañas mines. In 1860 he married Barry’s sister, Isabel, thus further cementing their relationship. The two men set about creating a modern, state-of-the-art mining enterprise at São Domingos.

The effect this had upon the immediate area and the wider region was truly transformative, and attracted the attention of Portuguese King, Pedro V, who visited the mine on 29 October 1860. This industrial complex with its model village was held as an example of technological and industrial progress, and a shining example of British civilisation. Mason was honoured by the Portuguese government, which made him Comendador da Ordem de Cristo.

In 1866 he was made Barão de Pomarão and in 1868, Visconde de São Domingos (for two lives). In 1897, the title, Conde de Pomarão, was bestowed upon him. The coat of arms he chose on his elevation to Conde de Pomerão were Non vultus instantis tyranni, (Not the face of an overbearing tyrant). Barry was also honoured by the Portuguese state, being appointed Comendador da Ordem de Cristo in 1876, and in the same year, Barão de Barry.

Mason and Barry’s success undoubtedly lay in their access to British capital to develop the property, but also in their ability to open a cheap and efficient export route which guaranteed the mine’s future. The mine was run on the Cornish system of tribute and tutwork and the language of the management was English.

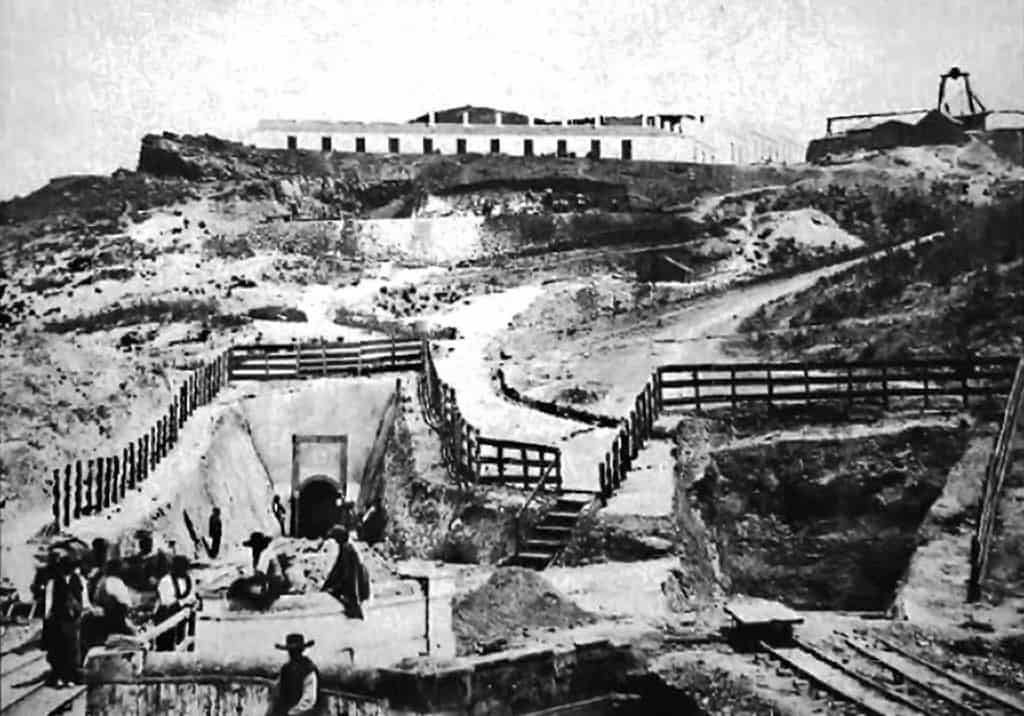

Twenty-seven Roman shafts and an adit were cleared out, enlarged, deepened and timbered, and two new levels were exploited below the Roman adit. Steam engines soon replaced manually operated pumps and horse drawn malacates. This solved the issues with flooding, as the mine had been forced to suspend operations in the rainy season, meaning it could only work for nine months of the year, meaning all the workers had to be paid off on 31st October.

The engines were imported from Britain to drain the deepening workings and to haul the ore to surface. Reservoirs to store both sweet water (for the steam engine boilers and domestic use) and acid water for industrial purposes (ore dressing etc.), were built, and hundreds of hectares of pine and eucalyptus were planted in compliance with the terms of the lease to ameliorate the devastation caused by the mining operations.

An 18-kilometre railway designed by Ernest Deligny was constructed to link the mine to Pomarão (Pomaron), the nearest navigable point on the Guadiana River, which opened to traffic amid much pomp and ceremony on St John’s Day (24 June) 1862. The line, which presented an engineering challenge on account of the mountainous terrain, replaced the need to convey the ore to Pomarão by road in carts drawn by 1,500 mules, which was both slow and costly.

Mason then applied for and received permission to import a steam locomotive from Tharsis. While this locomotive was being trialled, the railway was worked by mules which was highly expensive, involving the wages of scores of mule drivers as well as the cost of feeding and housing the animals. Mason was well ahead of the curve in putting into place a continuous and cost effective transport system for the exportation of his ores, and by 1864, São Domingos was the most productive copper mine in Europe and was employing some 900 people.

Pomarão rapidly became the fourth most important port in Portugal. The river was dredged between there and Vila Real de Santo António, the port located at the mouth of the river, to facilitate the conveyance of boats of greater capacity. Many vessels were engaged in conveying ore down river to Vila Real de Santo António where the cargoes were transferred to ocean-going ships destined for British smelters.

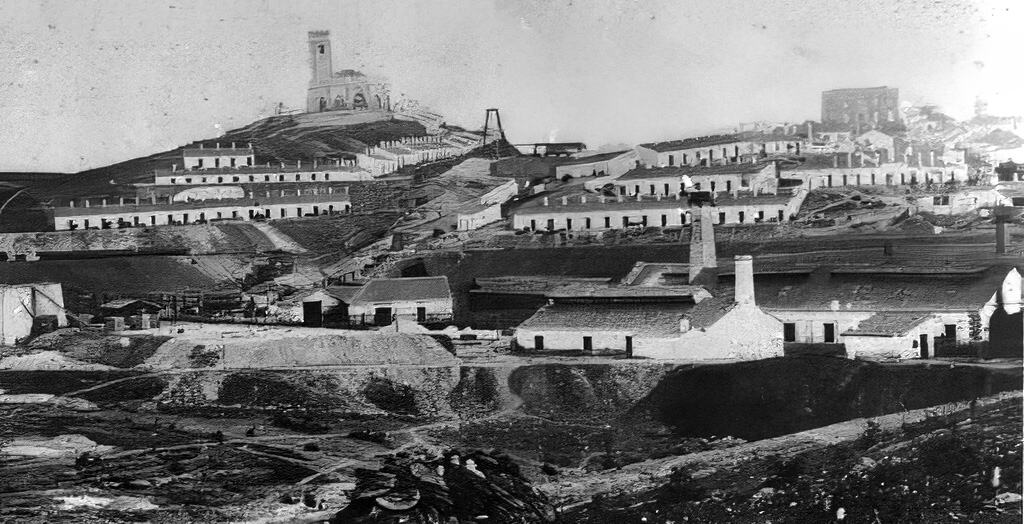

A village named Mina de São Domingos, soon mushroomed around the mine workings, as the once remote and uninhabited hill became a hive of activity. Within five years of the mine’s reopening, the company had constructed 275 one-roomed cottages on the hillside around the old hermitage to house its Iberian workforce, plus 14 management dwellinghouses and a two-storeyed house for the managing director, which was dubbed the Palácio. The foreign management lived in a separate district (see below) provided with leisure and sporting facilities. A British Consul was located Vila Real de Santo António, and he maintained vital rites of life registers.

The mine proved to be a dividend concern in its first five years, its profitability aided considerably by the British demand not only for copper ore, but also sulphur, which had been monopolised by the Sicilian government. Prior to this time, the massive amount of sulphur produced at the mine was an unwanted by-product which was dumped in huge piles in the countryside. Only a small percentage was calcined to produce a copper-rich calx for export. The São Domingos ores contained relatively high amounts of pyrite (about 49-50%) and the mine rapidly displaced the Avoca Mines in Ireland’s County Wicklow, which was then Britain’s chief supplier of pyritic ore.

A significant metallurgical advance was made when Glasgow chemist, William Henderson, discovered a method to recover copper from pyritic residues. São Domingos found itself at a distinct advantage, for the Spanish mines lagged behind implementing the process. Mason thereby monopolised the supply of sulphur to British alkali makers until at least 1866.

It was not until a group of Alkali manufacturers led by Charles Tennant of the St Rollox Chemical Works on the north bank of the Monkland Canal in Glasgow bought Henderson’s patent, that São Domingos’s hegemony in the market was challenged. They leased the Tharsis Mine, founding the Tharsis Sulphur Company. In 1873 another giant emerged in the shape of the Rio Tinto Mines, which halved the price of sulphur to the British chemical industries.

In order to respond to the chill winds of competition, Mason sought to make the operation of the São Domingos mine as efficient as possible. To this end, he obtained permission to begin opencast operations in 1867. He utilised rock drills in the seven underground levels opened into the side of the cutting, and seven stationary engines were erected for pumping and winding. In 1868, locomotives were deployed to convey the ore from the workings and to remove the overburden, and from then onwards, the whole of the hill covering the mine workings made way for a huge open pit.

The old hermitage was demolished and the mine offices and workers’ housing were torn down. A new model village for the Iberian workers was constructed in terraces further away from the mine, which was completed by 1880. The company had erected a new Catholic Church in this village by 1867, with bells cast in London from the mine’s copper ore. New management offices, which included residential quarters for the mine manager, were constructed in 1874 at a distance from the workings.

The pit was excavated to a depth of 32m, and the work to remove 45,000m³ of overburden continued until 1880. By then, the 40m hill had completely disappeared. The open pit eventually reached a depth of 122m, and the underground workings went down by a further 280m.

Metallurgical advances were made in the treatment of low-grade ores, and between 1864 and 1870, Mason experimented with a method of extracting copper from such ores. This necessitated the construction of a crushing plant, calciners, cementation tanks and dams. The machinery was imported from Britain. The resulting operations caused significant pollution to the air (through calcination) and watercourses (due to the leaching of the ores leading to acid mine drainage).

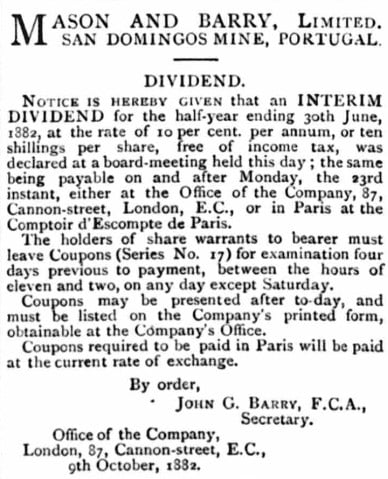

In 1878 Mason and Barry, who had acquired a number of shares in La Subina, was converted into a limited company. At this point, the whole of the shares were held by the founders and a few friends. Mason handed over the directorship of the company to his son in 1880. In 1881, it was noted that the nominal capital was £2,100,000 in £10 shares of which 185,164, representing £1,851,640, had been issued. The debenture debt having been all paid off, the lessees had recently disposed of a portion of the shares, representing £600,000, which were placed on the London and Paris market; but as more than two thirds were still held by Mason and Barry, they could not obtain an official quotation on the Stock Exchange list. The profits of the last year (1880), after paying expenses, were stated to have been £336,878, of which £200,790 were paid in dividends and £60,000 carried to the rest account. In 1881, the company declared a handsome dividend.

The São Domingos property eventually extended 20km from north to south (from Cerro do Ouro to Pomarão), and the company´s eventual land holding had a surface area of more than 6,000 hectares. About 20 million tonnes of material were removed over its life, of which nearly 15 million tonnes lies in spoil heaps around the mine.

The Cornish at São Domingos

Naturally, with his extensive links to British mining regions, particularly the Tamar Valley area, Mason employed Cornishmen at São Domingos from the very beginning, although their numbers were never great. They formed part of a discrete British community comprised of Welshmen, Scotsmen and Englishmen. In April of 1860, Plymouth newspaper, the Western Morning News, carried a report about the mines:

“A miner, employed at his mine, writes home that a magnificent lode of copper, silver, lead, &tc., is being cut, 60 fathoms in width, and it is anticipated that in the course of the month no less than between 2000 and 3000 tons of ore will be sampled. This extraordinary mine was formerly worked by the ancients, and it is calculated from the amount of scoria, that they took upwards of 250,000 tons of ore. In the course of the excavations, three complete water wheels have been discovered in a good state of preservation, made entirely of wood and beautifully finished. This valuable property is now being worked with great spirit, under the management of an English gentleman, of considerable mining ability, assisted by an efficient staff of Cornish miners.”

One of these men was Thomas Roskrow of Buller’s Row, Redruth, who had worked with Mason in Northern Spain. He had previously been employed in Brazil where his wife, Mary (née Moore) gave birth to a son named Thomas in 1837, so he therefore had some knowledge of Portuguese. He worked as a captain at the mines until his death sometime prior to that of his youngest son, Vanancia William Roskrow, at Redruth in December 1884.

Other Cornishmen included Captain James White of Marazion and St Ives, whose wife gave birth to a son at the mine in 1864, and Joel Lucas (1824-1901), a native of Virginstow just over the border in Devon, who married his Cornish-born wife, Jane Eggbeer, in Tavistock in 1846. He was the Mine Agent from sometime after 1860 when his daughter Elizabeth was born in Tavistock, up until the years before 1878 when he returned there. Thomas A. Down returned to Calstock from São Domingos in 1889, to marry Anita A. Lakeman of Callington.

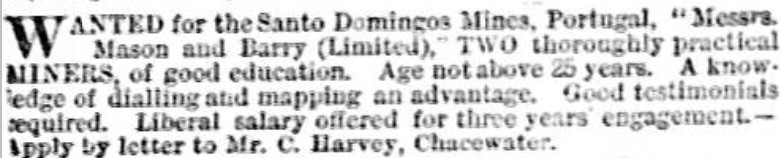

Another stalwart was Charles Harvey of Chacewater, who served as Mine Captain throughout the 1860s and 70s, until he left to manage the Twin Lake Mine in Colorado, USA in 1882, but not before he had acted as recruiting agent for the company in October 1881, prior to his move across the Atlantic.

He was replaced by his younger brother, Fred Harvey, who had arrived at the mine as a draughtsman along with another brother, Louis, who was a mechanic, and his unmarried sister, Marion.

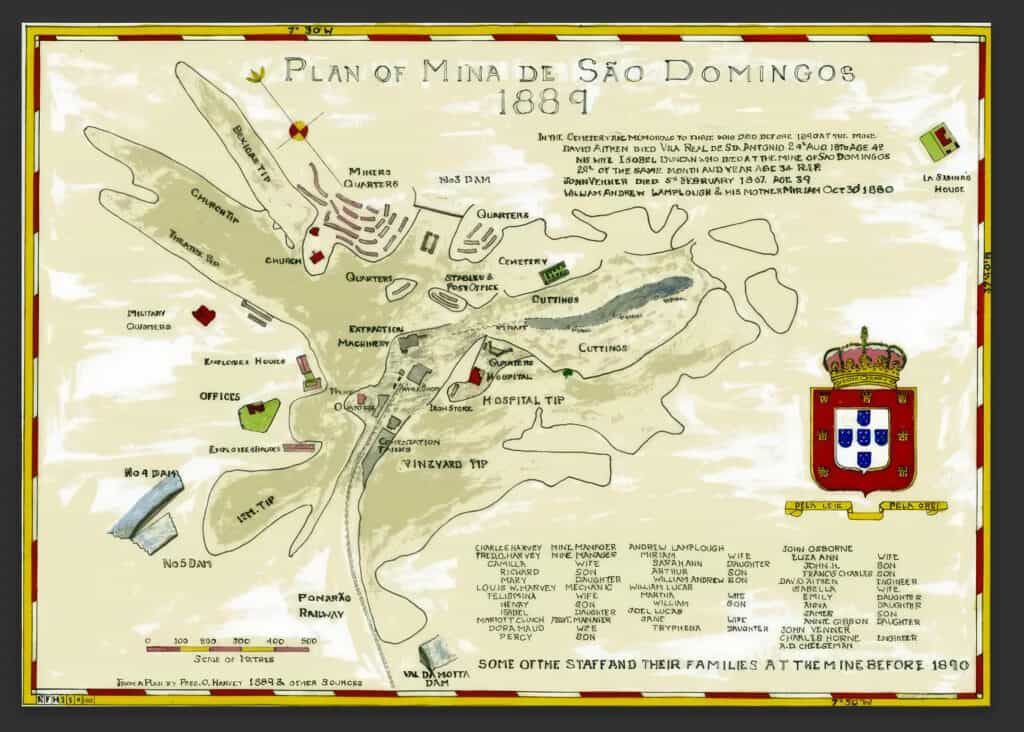

That the ‘Cousin Jack’ network was at play at São Domingos is evident due to ties of kinship and marriage depicted on a plan of the mine drawn by Fred Harvey in 1889, recording the surface features and listing the Cornish families working there. In 1873, Captain Charles Harvey married Joel and Jane Lucas’s daughter, Tryphena, who had been born at Gunnislake in 1854. There was no issue of this union and the couple lived apart for the majority of their married life. The plan also mentions William Lucas and his wife Martha, and John Osborne and his wife Eliza Ann. They and their children had joined Joel Lucas from Calstock in the 1860s. John Osborne returned to Britain and died aged 45 at his brother’s residence in Pensilva, Cornwall, in 1882.

The sons of some of these Cornishmen worked at the mine too, with John Henry Osborne serving as a chemist in the 1880s after an apprenticeship in Edinburgh, while Richard Harvey, Fred’s son, was employed as a mining engineer from 1915-18. Redruth ties were maintained with the migration of Frederick J. Rich, son of Captain William Rich of Pednandrea House. A graduate of the Redruth School of Mines, following his marriage to Redruth-born Josephine Sara, Rich had worked at mines in Tasmania and Cuba before he and his wife arrived in Portugal. The family advertised for a general servant in Redruth newspaper the Cornubian in 1908, and in 1913 Mrs Rich gave birth to a son there. The family was still at the mine in 1921. The Rich family had prior links with the Iberian Pyrite Belt, as Frederick’s older brother, Captain William Rich, had served as the Manager of the famous Rio Tinto mines.

Francis Tom Roskrow, the son of Thomas Roskrow of Osaka, Clinton Road, Redruth, became the chief engineer of the mining department. Roskrow had formerly worked for John Taylor and Sons Ltd. at the Ooregum Mine in the Kolar Goldfields, India, and had married a neighbour, Agnes, the daughter of mine stockbroker James Wickett of Penarth, Clinton Road, at the Redruth Wesleyan Chapel in 1909. In 1920, Agnes’s parents were looking forward to meeting her in Lisbon.

However, life was not easy for the Cornish at the mine. The climate was gruelling, particularly in the dry, dusty, suffocating heat of summer. In June 1912, a British employee remarked: ‘The heat is fearful tonight. Candles will not stand upright and butter and lard are liquid.” The atmosphere was frequently blighted by toxic fumes from the calciners, and contemporary documents make reference to the strange appearance of the mine which was enveloped in black smoke with a red dust rising from the ground.

The hot, moist air underground was not conducive to good health, as it was impregnated with sulphuric acid which quickly rotted clothing and footwear and damaged the lining of the lungs. Many mineworkers were afflicted by an ailment called gorrotilho, caused by excess inhalation copper droplets, which caused the throat to swell and close up, which inevitably meant a tracheotomy had to be performed. As at the Cobre Mine in Cuba which shared a similar geology, in 1878 the company installed baths at the surface, so miners coming off shift from the unbearably hot workings could bathe and become acclimatised to the difference in temperature.

Malarial fevers were commonplace, and bedbugs were also thought to be responsible for spreading fevers. Some of the British employees succumbed to disease in the early decades of the enterprise, making it difficult to secure labour. In 1864, Captain Roskrow was instructed to impress upon his workforce that anyone who absconded from the mine prior to the termination of his contract would face prosecution. Intemperance was commonplace among some of the expatriate British, leading to fights between the men, and accusations of being unkind to the Portuguese and Spanish workforce.

The simmering resentment was exacerbated when the Iberian miners compared their living conditions to those of the British. While they lived in a one-roomed 14m square windowless room built of whitewashed taipa (rammed earth) in a terraced block, and had to share a water supply, ovens and privies, the British resided in a separate barrio akin to a colony, as was common at mines such as Morro Velho and Gongo Soco in Brazil and at Tharsis and Rio Tinto in neighbouring Spain.

Their two or three-roomed cottages each with a toilet and gardens, were built in the Violeta district away from the Iberian miners’ accommodation on a higher level close to the brick-built Palácio, surrounded by gardens and a bandstand. For every three months a British employee spent at São Domingos, they enjoyed a two week period of leave.

They had exclusive access to facilities such as a lake with sandy beaches (Tapada Grande), tennis courts, a cricket pitch, a billards room, and a reading room and library. A walled and gated Protestant Cemetery (O Cemitério dos Ingleses) was built at São Domingos in 1860 for their exclusive use. The surviving headstones include a Purves from Scotland and a Clinch from Witney, England. Iberian miners and their family members had to be interred at Catholic cemeteries in the nearby villages.

Operating loosely along the lines of benign paternalism, the company built a hospital and dispensary, a church, a school, a theatre, the first electricity station in the province, the first telephone exchange, and sponsored two football sides, São Domingos and Guadiana. Both were founded in 1922, but only the former survives today.

However, the ill-feeling, undoubtedly fuelled by the demolition of the Iberian mineworkers’ housing and old Hermitage to make way for the opencast, first boiled over on setting and payday on 3 June 1865, an event that came to be referred to as the ‘3rd June Riots’ or ‘Revolution’. Two hundred miners had assembled for the distribution of the bargains at the usual auction on setting day.

However, they appeared to have been concerned that they would be cheated by the takers of the month’s bargains and demanded to be allowed to attend the measuring of the pitches. When the manager Joel Lucas refused, they tried to force entry into the main drive, causing two of the Cornish captains, Tom Roskrow and Charles Harvey, to draw their pistols and open fire, which resulted in injuries to some of the local men.

A tumult ensued when 400 enraged miners rioted. Captain Lucas was caught and severely beaten, causing his hospitalisation. His health was so adversely affected that he was obliged to return to England for a while. Captains Roskrow and Harvey fled into the mine, where they remained hidden at the bottom of the workings until the following day. The company took decisive action. Many of the rioters were imprisoned and punished, and a military unit was permanently stationed at the mine for over a decade until the company set up its own corps. Tribute and tutwork contracts were no longer auctioned in public and the employees were paid on the completion of their task, not at the beginning.

The relations between Captain Harvey and the Iberian mineworkers remained strained, and further tension occurred in 1875 when more of the mineworkers’ housing was demolished. His unbearable temper and general manner irked them in the extreme. He allegedly dared not set foot out of doors after dark, and went in fear of his life. Only when he had learned the hard lesson, that the locals would be led but not driven, did relations improve.

As they occupied senior management positions, the Cornish were no doubt in the eye of the storm when there were strikes at the mine in 1907 and 1911 over rates of pay. The company succeeded in reducing the mineworkers’ hours from 12 to 10 a day in 1907, and and reduced them still further to eight in 1911.

Over the course of the first decades of the twentieth century, the numbers of Cornish at the mines fell away as scientifically educated Portuguese managers, engineers and metallurgists were elevated for the first time to top managerial positions. Although they were only ever a small percentage of the British workforce at the mine, in terms of numbers, it is fair to say that the Cornish punched above their weight. An fictional historical novel set at São Domingos named Summer Lightning, by Pamela Oldfield (Severn House, 2006), explores some of the tensions within the expatriate community.

Decline, Closure and Legacy

Between 1859 and 1965, São Domingos produced about 25m tonnes of mineral, and in 1965 there were still 866 employees. However, the deposit was exhausted by the mid-1960s and Mason and Barry Ltd. stopped paying royalty to La Sabina. The company went into voluntary liquidation on 25th April 1968.

The departure of the company from São Domingos caused considerable acrimony among the workforce and local people. Employees had not been paid their wages and pensions were not honoured. According to the terms of the agreement between La Sabina, the owners of the concession, and Mason and Barry Ltd., the licensees, the whole of the property reverted to La Sabina, thus exonerating Mason and Barry of any problems associated with the mine and its post-operative remediation. La Sabina quickly moved in to asset strip the property of anything of mercantile value. It also inherited the miners’ housing in the model village, but failed to maintain it adequately, causing much ill feeling.

The environmental burden was also a heavy one, and acid mine drainage and contamination at the lunar-looking mine site remain largely unresolved. There has been little attempt at landscape remediation, although endemic plant species have successfully colonised the acidic post-industrial landscape, which offers fascinating opportunities for biological studies.

Attempts have been made to replace the mining industry with tourism, but this is nowhere near as advanced as at the Spanish mines of Rio Tinto and Tharsis.

Further Reading on São Domingos

Alves, H., Minas de S Domingos, Génese, Formação Social

e Identidade Mineira, 1997.

Booker, P., ‘The British Mine at São Domingos’, 48th Annual Report, British Historical Society of Portugal, 2021.

Ramos Pinheiro da Silva, Maria João B, ‘Narrating Personal and Collective History in Heritage Tourism: Conflicting Representations of the São Domingos Mine and Community’, Material Culture Review 71 Spring 2010, pp. 24-38.

Ramos Pinheiro da Silva, Maria João B, ‘São Domingos Mine’s English and Cornish Connections,’ in P. Claughton and C. Mills (eds.) Mining Perspectives: The Proceedings of the Eighth International Mining History Congress 2009, Cornwall Council, 2011, pp. 187-193.

Ramos Pinheiro da Silva, Maria João B, Mason & Barry e a

construção da Mina de São Domingos, Indústria, Turismo,

Globalização, 2021.

Visit São Domingos

Attempts have been made to turn the abandoned mine site into a tourist attraction with the creation of a walkway round part of the flooded opencast and the installation of interpretation boards in English and Portuguese. There is a mining museum in the village founded in 2004 by the Câmara Municipal of Mértola and operated by the Fundação Serrão Martins.

A four-star hotel now occupies the converted mining headquarters (the Palácio), with manicured grounds and a high-powered telescope for astronomy enthusiasts. The model village is well preserved and many of the houses are inhabited by families with a connection to the mine which closed over 50 years ago.

More online information about the mine and its community can be obtained from the excellent São Domingos Mine Studies Center (CEMSD). Visit it here

© Sharron P. Schwartz 2024

Pingback: 'Roman' through Kresen Kernow to a mine in South West Portugal - Cousin Jacks World