Brazil’s most Significant Cornish Community

Morro Velho

Unless otherwise stated, all content is © Sharron P. Schwartz, 2021, and may not be reproduced without permission

Brazil’s most Important Gold Mine

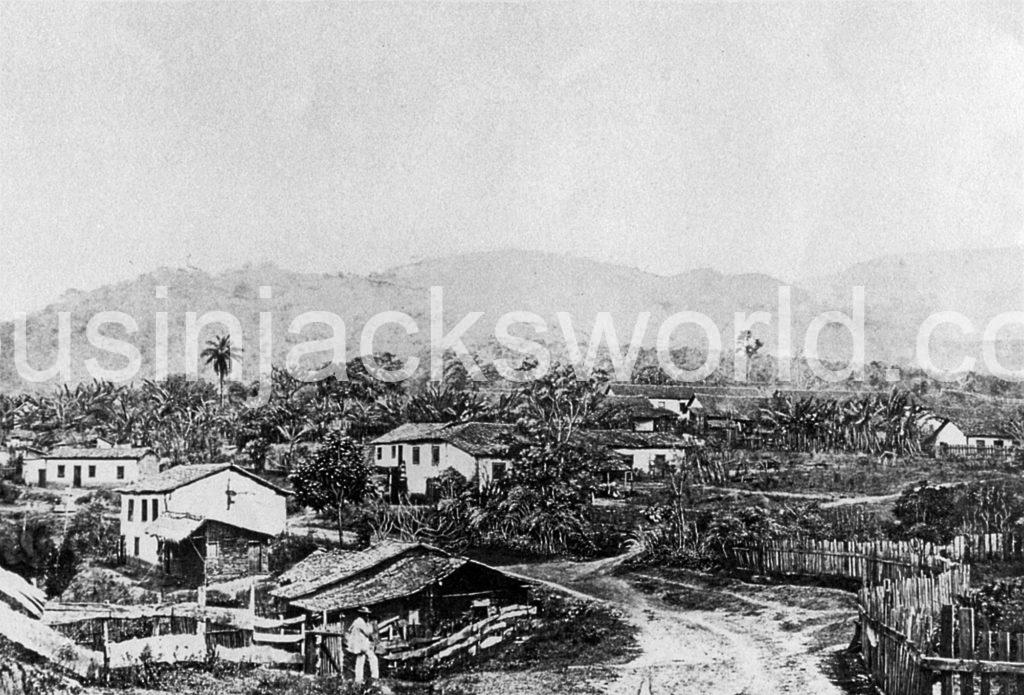

Morro Velho, in the State of Minas Gerais, is situated in a low valley in the northern suburbs of Nova Lima, a city formerly known as Congonhas de Sabará. Belo Horizonte is about 20km away and Rio de Janeiro, over 320km.

Gold mining in Brazil has a long history. The world’s first gold rush occurred in Minas Gerais over 100 years before that of California, and mines in this state have been in operation since 1725.

In 1834 Morro Velho came under the control of the St John d’El Rey Mining Company, a British enterprise which was established in April 1830 as a joint stock company. The company’s beginnings in Minas Gerais were less than auspicious. It obtained a lease from three British merchants and a German physician to work the São João del Rei Mines, and in the summer of 1830 a group of Cornish miners were sent out to commence operations.

However, the venture was mired in legal disputes, and the poor quality of the ore saw its abandonment within two years. But with their acquisition of Morro Velho, a mine that had been worked for up to half a century, the company literally struck gold.

The company also acquired additional mines in the vicinity: Raposos; Morro das Bicas (just south of Raposos); Bella Fama (about 2 kilometres southeast of Nova Lima); Gaia, Faria and Gabirobas (southwest of Honório Bicalho), Bicalho (Honório Bicalho) and Urubu (3 kilometres south-southeast of Honório Bicalho).

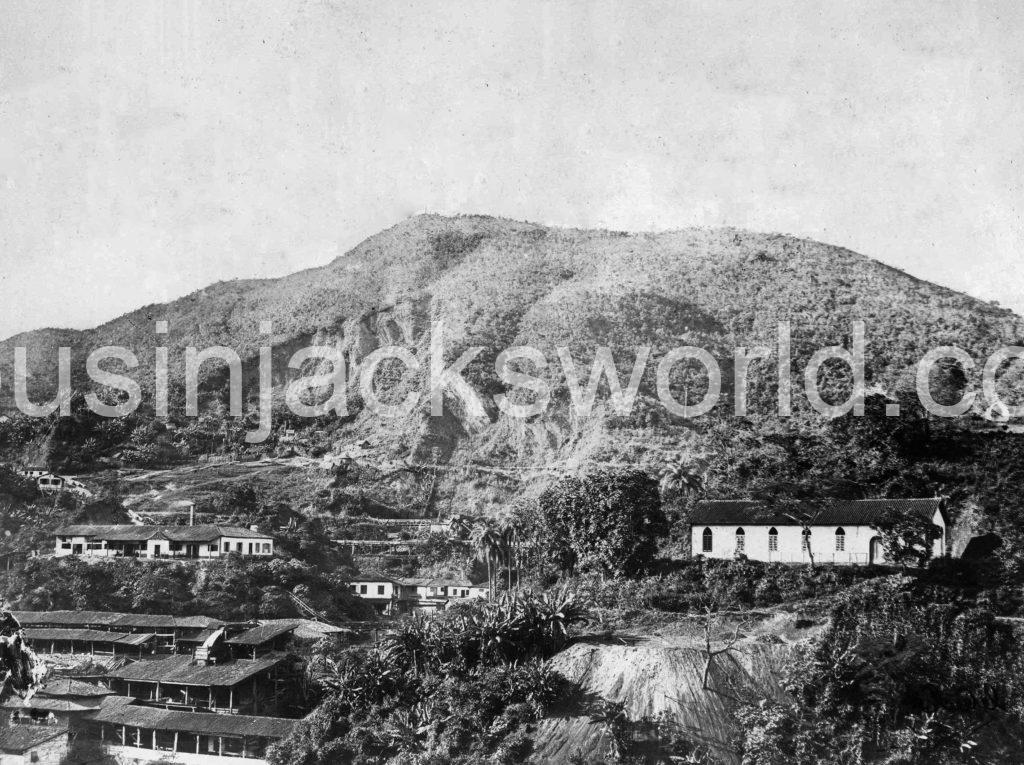

In 1915, Morro Velho was the deepest gold mine in the world, its air-cooled shaft attaining a vertical depth of 5,824 feet (about 1775m). Today, it is part of the AngloGold Ashanti company.

Brazil’s most Significant Cornish Community

Morro Velho is situated at an altitude of about 600m above sea level. Hemmed in at the top of a low valley impedes the circulation of air, and it was not considered to be as healthy as other British mining establishments in Brazil. Hot by day and chilly at night, people complained that the four seasons of Europe could come and go in a day. The dry season lasts from April to October, with average temperatures of 16-22C. Thick fog and drizzle often characterises the hours of dawn, which burns off by mid-morning.

Around midsummer are showers called the Rains of St John, followed by heavy downpours in August. The tropical rainy season is heralded by immense thunderstorms of hail and rain in November. At the end of January or early February, a fair-weather interval arrives called the veranico (little summer) a dry period accompanied by intense heat, strong sunlight and low humidity.

Although the village of Gongo Soco was the first Cornish community in Brazil, that of Morro Velho was larger and existed for far longer. The St John d’El Rey Mining Company actively encouraged the migration of mineworkers’ wives and children, and a thriving community developed close to the mine workings.

Although the Brazilians failed to make any distinction between the Scots, English, Welsh, Irish or Cornish, referring to them all as o inglês (the English), the Cornish were by far the largest ethnic group at Morro Velho, numbering some 350 in the 1860s. It was remarked that the men preserved their ‘peculiar accent’ and their superstitions, giving this mining community a real Cornish character.

Numbers of Cornish present at Morro Velho fluctuated in the late-nineteenth century, particularly in the aftermath of major mine collapses in 1867 and 1886, when many repatriated. But the Cornish presence at Morro Velho persisted well into the 1930s and beyond.

Getting There

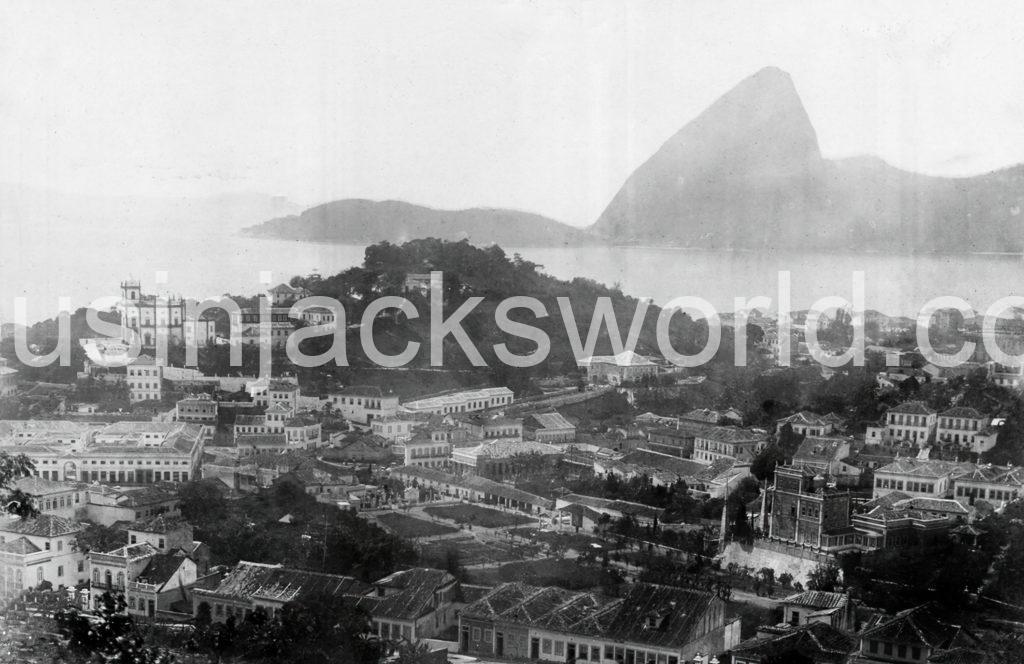

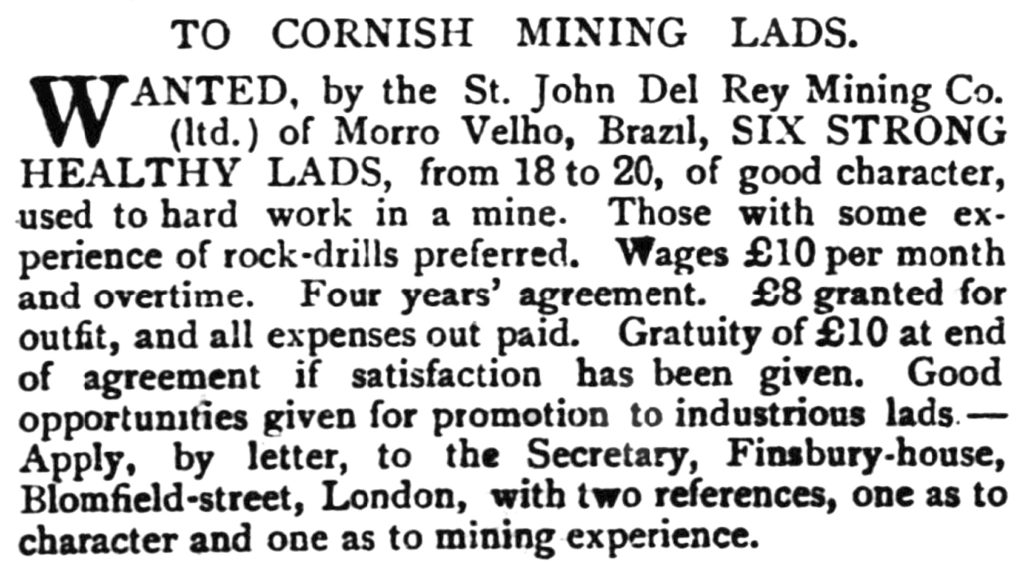

In the early- to mid-nineteenth century, the majority of mineworkers left Cornwall for Rio de Janeiro aboard a Packet ship from the Port of Falmouth. The journey took up to two months. In 1850, Falmouth lost most of its Packet trade to Southampton, so after that time most ships to Brazil left from there, or from the Port of Liverpool. Improved railway links from Cornish towns made the journey to these English ports easier as the century wore on. By the early-twentieth century, the Transatlantic crossing by steamship to Rio de Janeiro could be made in around 17 days.

In the mid-nineteenth century, after clearing customs in Rio, Cornish migrants faced a month-long journey to the mine. There were two routes. The first entailed a boat journey across Guanabara Bay and then up the Rio Estrela which meandered through swampy terrain, to the Porto da Estrela (58km north of Rio). This was then an important port and the gateway to the rich mines of the interior. From there, the journey inland was continued by mule. The ascent of the Serra da Estrela (a prominent mountain range) via a zig-zag road which had been paved at great expense by Emperor Dom Pedro I (1822-31), took 2-3 days.

After crossing the River Parahiba by ferry-boat into the Province of Minas Gerais, travellers proceeded to Barbacena where the alternative land route joined the road to the mines. This second route from Rio was far longer, and traversed the towns of Vassouras, Valenca and Rio Preto. From Barbacena, the road continued through Ouro Branco, Ouro Preto and Marianna, before swinging northwest to Gongo Soco which was, until 1856, the largest British mining settlement in Brazil.

From Gongo Soco the road led westward over a very high hill to the village of Caethé. From there it went to Sabara, one of the largest settlements in the mining district, where goods such as candles and blankets were manufactured for the mining companies. Morro Velho lay just under 20km away from Sabara, the route traversing very bad, hilly countryside.

The Cornish didn’t like the river route from Rio. The boats which carried four people, their luggage and three or four mules, were easily capsized and there was the added danger of contracting yellow fever in the swampy terrain. By the late-nineteenth century, improved roads and facilities meant that the journey from the coast to the mines was safer, speedier, and more comfortable.

The Morro Velho Mine

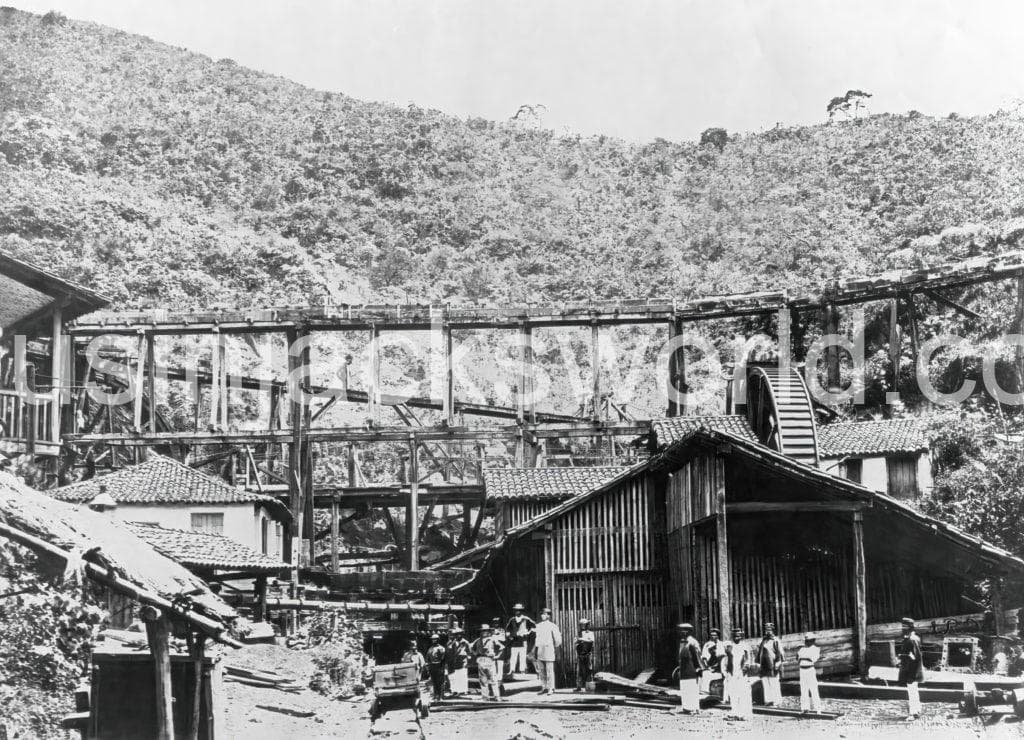

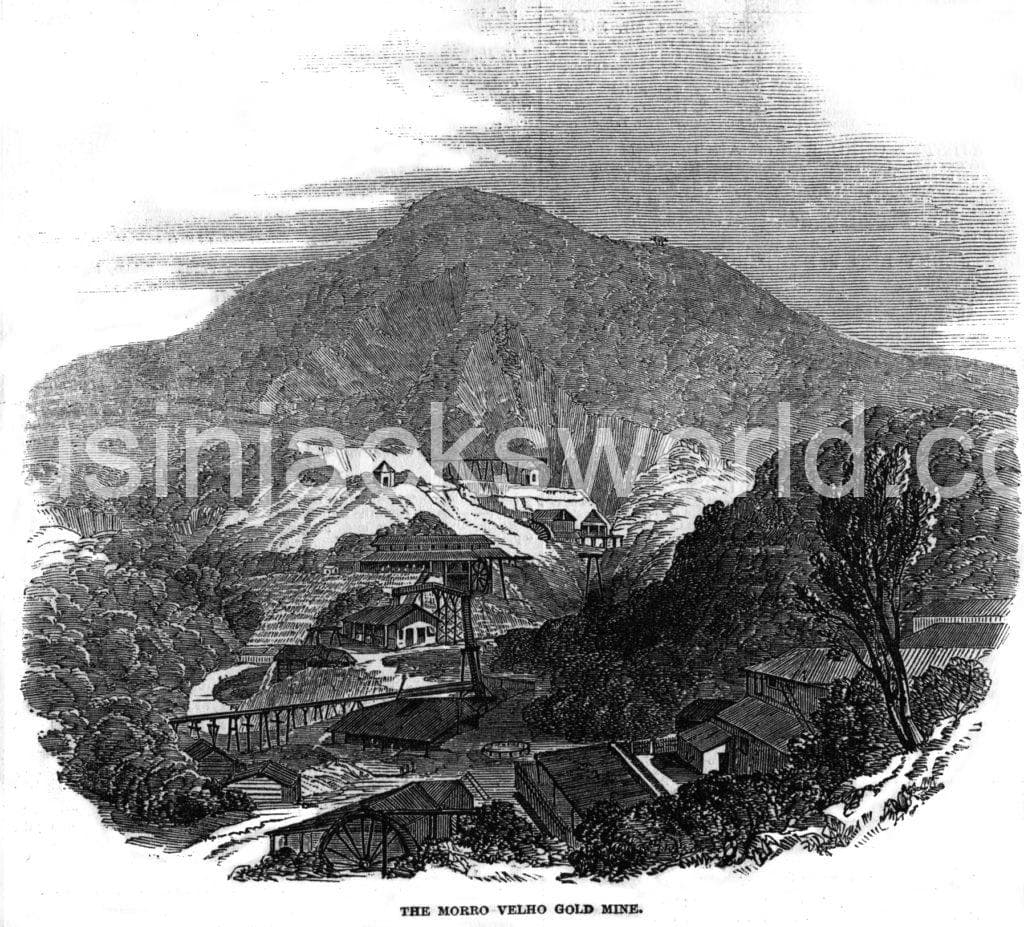

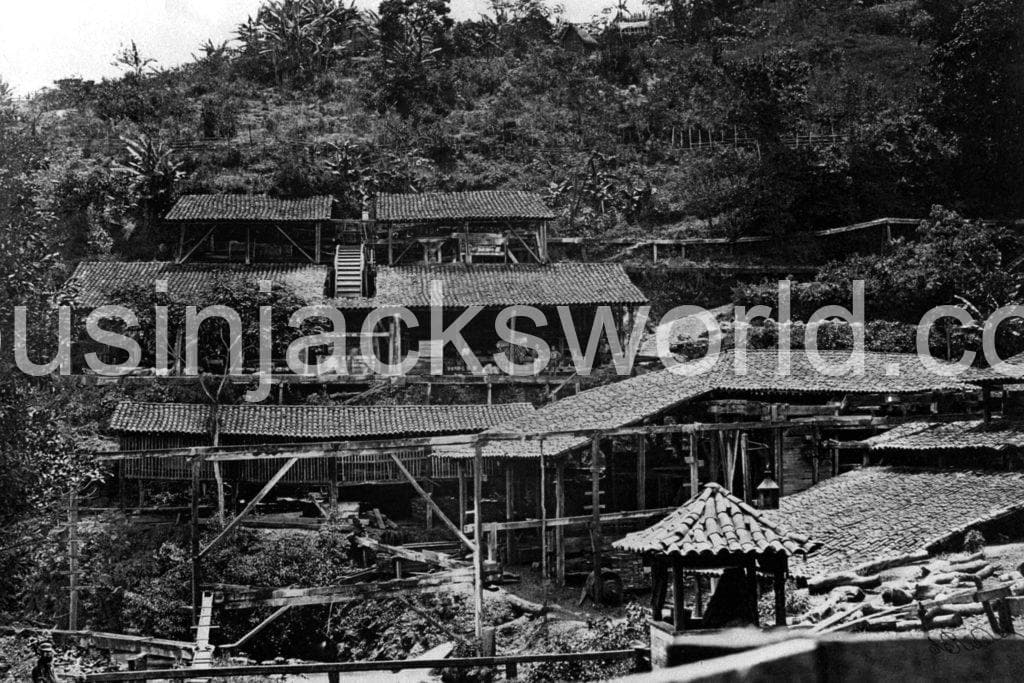

The former owners had worked the mine as a talho aberto (open cast), but the St John d’El Rey Mining Company soon extended their property and drove a deep adit to facilitate deep lode mining. The river that formerly flowed through Nova Lima was diverted to power the water-driven machinery at the mines, to wash the ore, and to conduct the tailings away through launders.

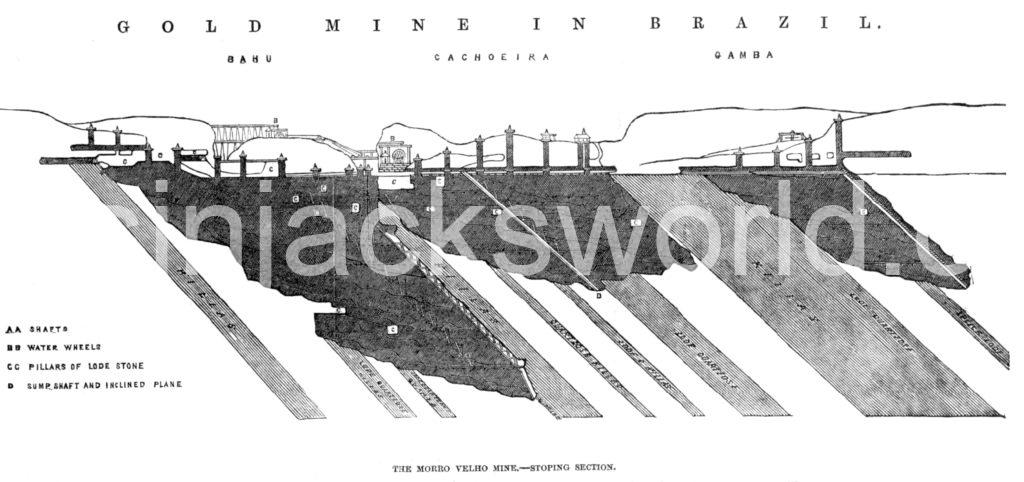

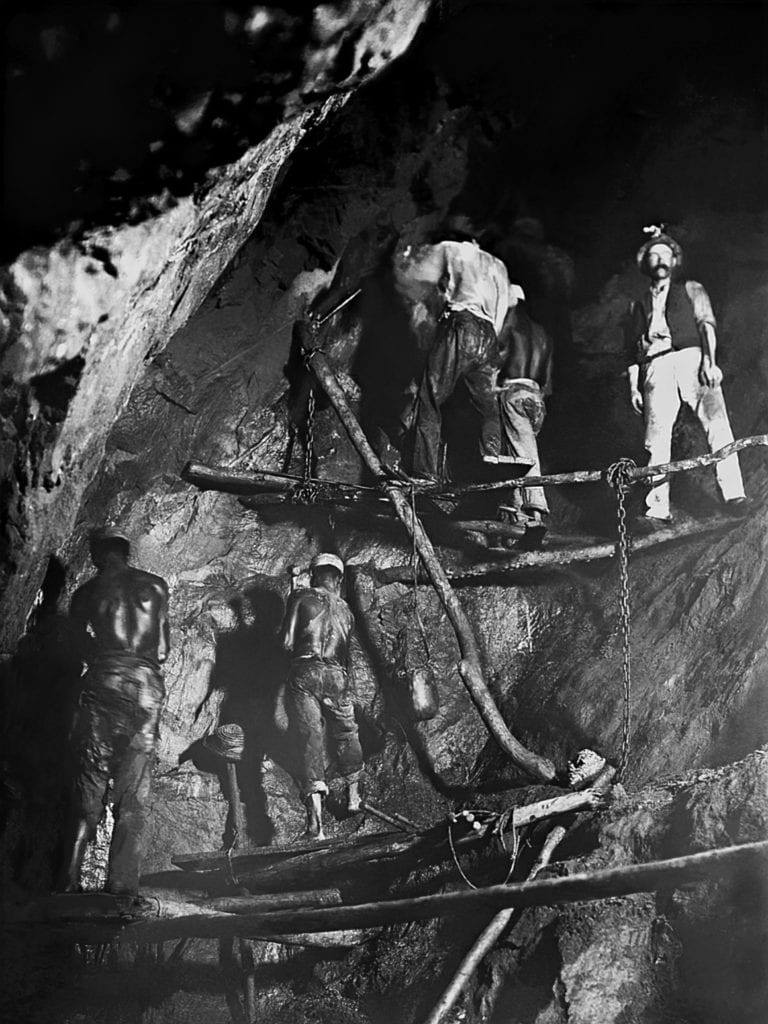

The nucleus of the mine was located on the western slope of the valley above the Ribeirão do Morro Velho which acted as a drainage channel. The mine consisted of three workings contiguous to each other: Bahu, Cachoeira and Gamba. These were drained by the same large waterwheel. As the lode dipped at an angle of 46 degrees, the main haulage and pumping shaft were on an inclined plane.

There were two waterwheels for drawing stuff; one for the saw-mill; one at the reduction works for working the amalgamation barrels, and six others working 96 head of stamps. The pounding of the stamps echoed round the valley continuously. Dotted amid the waterwheels were small whitewashed kiosk-shaped buildings which accommodated the brakemen who controlled the stuff being conveyed up and down the shafts. There wasn’t much timber in the vicinity of the mines, but the nature of the geology (quartz rock) meant that the mine workings did not need to be supported by as much timber as was required at Gongo Soco.

On the northern bank of the river, which was little more than an industrial drain thick with mud and arsenical slime in the dry months, and a furious torrent in the rainy season, were the mine entrances. Below these lay the smithy, spalling floors and mining office. A whitewashed kitchen for the black workers stood out. Higher up, and safely away from the mine workings, stood the powder house (where the explosives were stored), and close by was the Protestant cemetery.

A small bridge crossed the river to the southern bank where the amalgamation house was. Further up, and accessed by a great ramp, were the stables. Above this was the Casa Grande and the Venda (company stores) beyond which stretched the Colônia Inglêsa (English Colony) where most of the company’s British employees and their families lived.

In 1849 the company was employing about 1,200 people and 6,000 tons of ore were stamped. As the ore was pulverised by the stamps it was washed by a stream of water. The resulting slurry passed out of the stamps’ boxes through a fine copper grate. Here it was carried down into a strake – a slightly inclined plane covered with hides – which trapped the gold and the heaviest particles of sand. The lighter, earthy material was carried away. The hides were taken up every two hours and washed in separate boxes. The sand of the three hides closest to the stamps was taken straight to the amalgamation house. The material from the skins further away was once more passed over the strakes.

The amalgamation process was simple. The gold-bearing sand was put into barrels with mercury, and revolved quickly by a waterwheel for 20-30 hours until all of the gold was amalgamated with it. The contents of the barrels were then poured into a ‘saxe’ (a long, inverted box moving horizontally in a trough) into which the amalgam was deposited, and the sands washed away at either end.

Every 10 days the ‘saxe’ was opened and the amalgam passed through a chamois leather to squeeze out the mercury, which could be re-used. The content of the chamois leather was then burnt off in a furnace, and yielded from 25-30 per cent of gold. The gold dust was placed into leather bags and taken under armed guard to Rio de Janeiro, where, in the early days, it was transported by Packet ship to Falmouth.

For around a decade after the commencement of operations, the company achieved little. The ‘quinto’ (royalty or tax) was lowered from ten to five per cent in 1845 and was eventually abolished in 1859. After this time the company’s fortunes began to improve.

A calamity befell the mine when, during the night of 21 November 1867, a fire broke out in the lower levels, setting fire to the timberwork holding up the cavernous stopes which tore through the workings. After fruitlessly fighting the fire for days, the Superintendent ordered the shafts to be sealed to starve it of oxygen. The fire was eventually extinguished, but not before it had consumed the timber stull-work holding up the workings, which then caved in.

Many Cornish were laid off after this disaster. The next seven years were spent raising capital and sinking two new vertical shafts with improved haulage arrangements which cost in the region of £50,000. Fortunately, the shareholders and the Board of Directors kept faith with the project and the company limped on by working the upper levels of the mine, re-working the dumps, and exploiting a small venture nearby.

But the relief at being able to re-open the mine in 1870 and a return to profitability was marred by the unwelcome news of the fraudulent activities of the superintendent, James Gordon. In his 20 years at the helm, he had been diverting resources from the mine to benefit personal mining ventures. Worse still, he had been ‘picking the eyes’ out of the mine by working only the best parts of it, much to the dismay of his Cornish mining captains, who blew the whistle on his mismanagement. He was dismissed in 1875.

For five years the mine passed through a period of flux, as superintendents came and went, and the ad hoc administration and lack of morale meant the company’s fortunes continued to wane. All that changed in December 1884 with the appointment of a brilliant young Cornishman named George Chalmers. He proved to be the right man in the right place. No sooner had he begun to get to grips with the many problems besetting Morro Velho, disaster struck.

On the night of the 10 November 1886, the Cornish timbermen raised the alarm by noting that a timber cut specially to fit into the stull-work was too large. The ground had moved. By the time any remediation work could be undertaken, this ground gave way burying 10 men. The catastrophic subsidence continued for weeks, closing the mine and sending the company into liquidation. A skeletal Cornish workforce was kept on, but the majority returned home to Cornwall, or migrated elsewhere.

The disaster was a unique opportunity to completely modernise a mine that Chalmers believed to be one of the most promising enterprises in the mining world. He proposed radical plans to salvage the company by sinking a new mine in the same lode through vertical shafts at unheard of depths (700 m from surface). He also planned a completely new and modern mill.

At first the Board of Directors were unconvinced and baulked at the depth of the shafts. Eventually they were won over and Chalmers returned to Brazil in 1887 to restore Morro Velho. Reconstruction of the mine began in the 1890s. Within three years production exceeded the 200,000 metric tonnes of raw ore occasionally attained in the mid-nineteenth century. By 1910 that figure had doubled. Within five years of opening the new mill, gold bullion production had surpassed the record level of the 1860s and continued to grow.

Chalmers’s later projects included the electrification of the works using hydroelectricity, a plant to deliver cool air into the incredibly deep workings, and an electric tramway opened in 1913, which connected the mine with the station at Raposos. A plaque to this tenacious Cornishman was placed over the entrance to the Main Adit in 1901. After 40 years with the company, Chalmers left his position as superintendent in 1924, leaving his son in charge, and served as a consulting engineer until his death in 1928.

The Brazilian revolution in 1930 marked a watershed, for this significantly changed labour and currency exchange practices. The advent of unionism led to strikes between the primarily European supervisors and the Brazilian labourers, and by the Inter war period the Cornish involvement at Morro Velho was largely over.

In 1957, the controlling interests of the company were bought out by a group of investors primarily interested in the iron ore of the area. The investors sold the company’s iron lands to the Hanna Mining Company, based in Cleveland, Ohio, and the 130-year tenure of the Saint John d’El Rey Mining Company came to an end.

The Colônia Inglêsa (English Colony) at Morro Velho

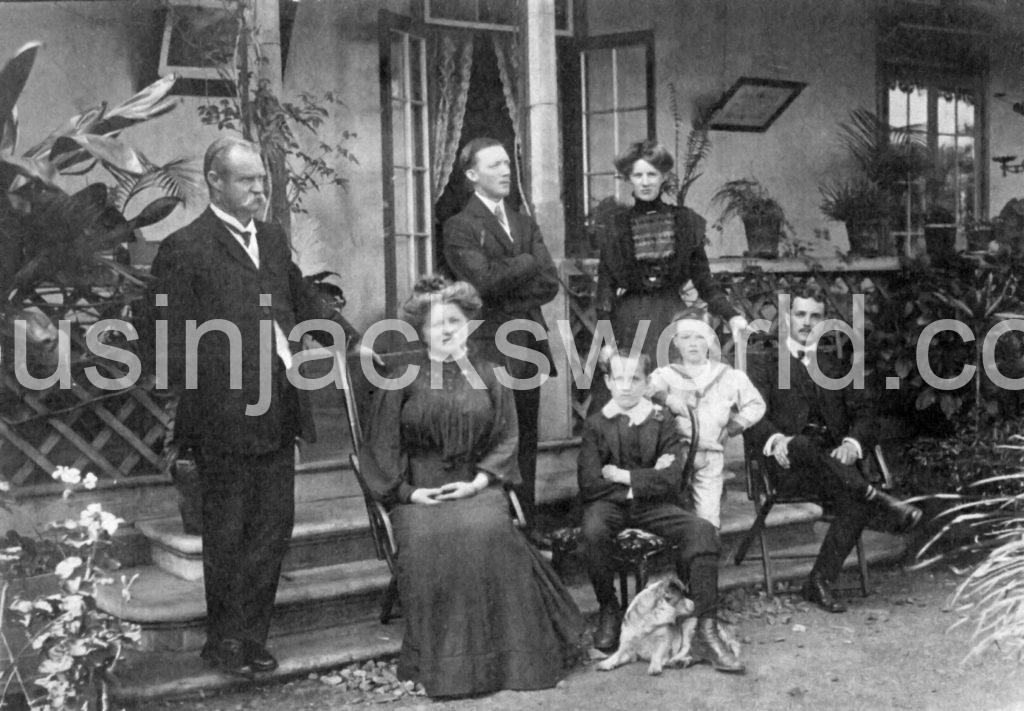

The British resided in a purpose-built village named the Colônia Inglêsa. This was sited to the south west of the hill around the Casa Grande (Count House or Mine Office) in a well-drained area that became known as the Retiro. The Colônia Inglêsa eventually encompassed the Bairro das Quintas where the British Club was located.

The Casa Grande was a long, vine-covered single storey building painted an official yellow with a red tiled roof. It was fronted by a veranda that had been built to receive the Emperor of Brazil, which opened out onto an immaculate English-style law set with gravel pathways. To the west and at right angles to it was the Sobrado, a guesthouse where visitors to the mine received legendary hospitality.

Separate living quarters for labour from other parts of Europe, such as Germany, were constructed beyond the Retiro by the late-1860s. This was of a standard that fell below that provided to the company’s British employees. The European labour-force was separated from the black slaves who resided in well-defined areas named Timbuctoo and Boa Vista, and the majority of the Brazilians who resided in the nearby town of Vila Nova de Lima. There were, in effect, two separate communities: the town itself and the ‘village’.

The well-built housing of the Colônia Inglêsa resembled the whitewashed single-storey local architecture, but had a definite British aura which was evident in the railed flower-beds, neat lawns, and cottage-style gardens boasting varieties of plants introduced from Britain. British notions of class were apparent in the Colony’s housing. Those with a veranda were reserved for senior management. The houses were rented from the company, the tenant paying in the region of R$500 to R$1,500 a month (Brazilian Real).

The three-acre hospital garden was said to have been particularly well stocked with peas, beans, potatoes, turnips and cauliflowers, as well as many indigenous vegetables, and included orange and banana trees. For several years a horticultural society thrived. An octagonal whitewashed and tiled building housed a library with 920 volumes, 800 of which were for loan, the remainder for school purposes.

The growing population of miners and their families from Britain resulted in the company’s decision to allow a small chapel to be built in the 1840s. An even larger one with a schoolroom was constructed in the 1850s to coincide with the arrival of an Anglican chaplain who was to administer the rites of life and to instruct the children in Christian principle, as well as to institute an acceptable British curriculum. After years of lobbying by the company’s directors, the British Government passed the Morro Velho Marriage Bill in 1867. This Act legalised marriages consecrated by Anglican clergy at Morro Velho.

Morro Velho: A Cornish Community in the Tropics

The Church at Morro Velho was said to have been fairly well attended in dry weather. The congregation numbered about 100 souls, the miners sitting on the left side and the mechanics on the right. But the Cornish, who were mainly followers of Wesleyan Methodism, infrequently attended this church. In the mid-1840s, the Mine Superintendent, George Keogh, actually fined the ‘English’ miners for non-attendance. Indeed, it was noted in 1867 that ‘Tregeagh’ sometimes complained that he had ‘lost all relish for his prayers’.

The Anglican arrangement collapsed at Morro Velho in the late-nineteenth century, mainly due to the cave-in of the mine and the repatriation of the mine’s employees to Britain. By this time occasional visits, chiefly to perform the rites of life, were made by Anglican chaplains from Rio, although the school did manage to keep going. These visits eventually ceased, and calls were instead made by American missionaries.

In 1910, George Chalmers arranged for the Chaplaincy to be re-opened, and the school was moved to the church. In 1914 a new church was built away from the noise of the quartz crushing mills. The congregation was said to have been regular and faithful, rather than large.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the Cornish were very involved in the provision of Sunday Schools for their children. One of the most well-known Sunday School teachers was Henry Davey Cocking of Camborne. Although he was a Methodist, he wasn’t a strict Teetotaller, as he brewed his own beer (which had not been forbidden by John Wesley) using imported hops! As at chapels in Cornwall, the children looked forward to the annual tea treat.

That of 1857 involved around 100 company employees and their families, including scholars from as many as three Sunday Schools. In the afternoon, headed by the minister, some 60 children brandishing banners and flanked by their Sunday school teachers and two Head Mining Captains, paraded around the Morro Velho establishment accompanied by an amateur brass band. The party partook of a tea of oranges and plum cake voluntarily provided by the community.

Hymns and recitations, tunes from the band, addresses to the audience and the presentation of a book to each scholar for good attendance at Sunday school followed. Bemused Brazilian onlookers stood on the hills nearby to witness the parade, one of the Sunday School banners declaring Dios Vos Guarde, (God Protect You). This was an attempt to foster good relations with the host community that saw several Brazilians invited to the festivities, including the Roman Catholic Vicar of the neighbouring parish.

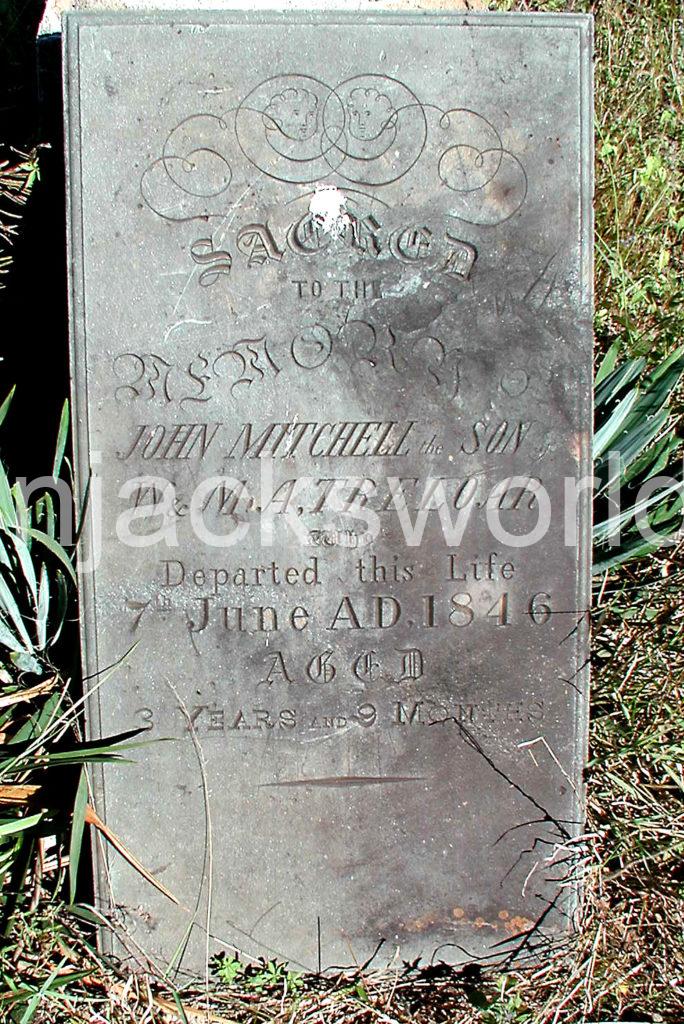

But there was not a high degree of social interaction between the communities, as is revealed by an examination of the parochial registers from the mid-nineteenth century for the Parish of Congonhas de Sabara (the former name of Nova Lima). For most of the nineteenth century, the Cornish almost exclusively married among themselves, with some even returning home to Cornwall for a bride. George Keogh forced one man to convert to Catholicism to permit his marriage, but during his 40 years at the helm, George Chalmers discouraged marriage with Catholics, and relations of any kind with black inhabitants were taboo. At Morro Velho the British applied for and received permission from Emperor Pedro II to set aside their own Protestant burial ground. This reinforced a sense of separation and exclusiveness.

The annual miners’ festival was centred on St John the Baptist’s Day at Midsummer, a celebration that had for centuries been popular in Cornwall, and had a distinctly Cornish flavour. It involved the lighting of tar barrels, a bonfire and a feast. By the late-1850s it has become an annual event and was a day off for the entire workforce. Even the slaves were included.

It was run like a Cornish parish feast day, featuring Cornish wrestling matches, a variety of gymnastic games and athletic races (for which prizes were awarded), displays of Cornish and ‘native’ slave dances, circus attractions, brass band and other music, a bonfire and fireworks, and a sumptuous feast. Opened by a salute of guns, it was presided over by the company superintendent and the local baron. It usually drew crowds of 2-3,000. Toasts were made under the national flags of Britain and Brazil, and God Save the Queen always ended proceedings.

A sports club was later constructed by the company at the Quintas and was complete with facilities for soccer, tennis, cricket and pool and was only open to members of the British community. An Amateur Dramatic Society was set up, in which the Cornish element predominated, and this put on plays and musical evenings. By the early twentieth century, Brazilians were often invited to their performances.

By the turn of the twentieth century, cricket and rugby matches were popular as they were also in Cornwall at this time. In 1913 there were two teams, one named ‘Cornwall’, consisting entirely of Cornish immigrants, and the other ‘Morro Velho’ that included Cornish, Morrovelhenses, Welsh and English.

Although members of the Brazilian population rarely visited the Quintas, football, which had been introduced primarily by young Cornish miners, caught on at nearby Nova Lima. The same thing had occurred in Pachuca, Mexico, where Cornish miners helped to popularise the sport. This led the St John d’El Rey Mining Company to donate the ground for the Vila Nova Athletic Club’s football stadium. The club became known as the Leão do Bonfim as the football ground sported sculptures of lions, seen as symbolic of British royalty.

In addition, there was a Freemason’s Lodge which catered for those men who had joined lodges in Cornwall, and the library carried copies of Cornish newspapers such as the West Briton and the Cornish Post and Mining News. During the rainy season many Cornish liked to go on fishing trips to the River das Velhas some two miles away, and the youngsters enjoyed swimming in the pool created by the company at the River Rego. Shooting wild game was also a popular distraction among the senior management.

However, there was little entertainment specifically for Cornishwomen outside of the odd performance with the Amateur Dramatic Society, so many devoted their time to helping to organise the annual tea treat and miners’ festival. Some found it difficult to adapt to life in the tropics. One woman pined away and died of homesickness in 1867. This so alarmed the company, that it considered sending another woman in apparent distress back to her native community to avoid a repeat of this unfortunate occurrence.

The Question of Slavery

Britain abolished slavery in 1833 yet in countries like Brazil, where slavery was legal, British-owned mining companies continued to employ slave labour. The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Association, with its goal of universal emancipation, campaigned for an end to this practice.

However, the realities of the Brazilian labour market forced the St John d’El Rey Mining Company, the single largest employer of slaves in the State of Minas Gerais, into confrontation with British foreign policy. Despite the disquiet of many shareholders and the general public, the company enjoyed support in high places, and it wasn’t hard to dilute the 1841 petition presented to Parliament by Lord Brougham, a prominent abolitionist.

Although the purchase of new slaves was banned, supporters of slave-owning mining companies successfully lobbied lawmakers to strike clauses prohibiting the renting of slaves. Brougham’s Act of 1843 was rendered toothless by the British mining companies operating in Brazil, who simply switched to renting slaves from local owners. Between 1830 and 1845, the St John d’El Rey Mining Company had purchased around 500 slaves.

The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Association then sought to stamp out the Atlantic slave trade by coercing Brazil to conform to the terms of the British-Brazilian Treaty of 1826, which it had ratified but failed to enforce. The Aberdeen Act of 1845 gave the Royal Navy authority to stop and search any Brazilian ship suspected of being a slave ship on the high seas, and to arrest slave traders caught on these ships.

Moreover, the Act stipulated that arrested slave traders could be tried in British courts. This provoked outrage in Brazil, where it was seen as a violation of the free market, freedom of navigation, and an affront to Brazilian sovereignty and territorial integrity.

In 1849, criticism of the treatment of slaves at the Morro Velho Mine appeared in the British press. The mortality rate among the enslaved ‘borers’ (underground drillers) was alarmingly high, and calls were made to end the wholesale sacrifice of human life. The Cornish largely supported this stance, not just because slavery had been censured in their local chapels, but because 500 Cornish miners would be needed at Morro Velho to prevent a decline in productivity if the slave borers were dispensed with. However, such a move was unlikely to have ever happened, as it would have proved too costly to the company.

In fact, the company capitalised on the demise of British-run mines at Cata Branca and Gongo Soco, by renting their slaves. These could now be hired at their peak productive years and dispensed with when they had outlived their usefulness. Consequently, the slave population at Morro Velho actually increased.

In September 1850, new legislation outlawing the slave trade was enacted in Brazil, and as a result the Brazilian slave trade ceased in the mid-1850s. But as slavery itself was not abolished until 1888, the use of slave labour continued at Morro Velho. In the 1860s, the St John d’El Rey Mining Company employed over 1,500 slaves.

Travel writer, Richard Burton, visited the mine in 1867 and reports that the slaves were well clothed, fed, and accommodated. They were paid commensurate to their age, sex and ability, and could be legally married. They attended church and had certain legal rights under the law. All received medical treatment when required and could work towards their emancipation, as manumission was held to be a Catholic duty.

However, their lot was far from pleasant. For years they had endured beatings and one man was reported to have been locked in a cell by George Keogh for three days without food in the mid-1840s. Although the beating of slaves as a punishment had been abolished by 1867, it could still be prescribed after appeal to the Superintendent by the heads of department. He then administered a flogging with the Brazilian cat of split hide. And rebellious newcomers were still being ‘broken to harness’.

The slaves were also subjected to an inhumane fortnightly muster called the Revista. They were separated by sex and lined up outside the Casa Grande to be minutely inspected by the mine management and the medical officers. Their uniforms and the fact that they were barefooted branded them as slaves.

Females wore a white cotton petticoat with red bands round the lower third, a cotton shawl striped blue and white, and a bright red kerchief bound round their hair. The red bands on their dresses were symbolic and attained for good conduct. Seven bands denoted freedom, but only if the company chose to allow this to occur, and often it did not.

The slave men wore white shirts, loose blue woollen pants, red caps and cotton trousers. The good conduct men wore tailless coats of blue serge bound with red cuffs and collars, white waistcoats, overalls with red stripes down the seams, and the usual bonnets. Each had a medal with the Morro Velho stamp, which was a badge of approaching freedom.

Records show that Cornishmen caught striking, or ill-treating slaves at Morro Velho were fined. Although Burton believed slavery should be abolished, he concluded that this was untenable as the black population was ‘too savage’ to live in the presence of civilised men.

There was considerable fury in 1879 when it was discovered that 200 slaves acquired in 1845 from the British-run Cata Branca Mine had been promised freedom after 14 years, but the company had reneged on this. Soon after this, the Brazilian authorities freed the slaves under pressure from local abolitionists. This case was one of the early events leading to full abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888. By this time, the transition to a free labour system at Morro Velho was almost complete, as the number of slaves for hire had fallen, making slavery expensive and therefore unprofitable.

Legacy

Back in Cornwall, Morro Velho became a household name in many Cornish mining villages, as families moved back and forth to the mine, and families in Cornwall waited for ‘home pay’ to be remitted. Many local chapels and organisations benefited from charitable collections sent home from Morro Velho.

Those who eventually settled at home left a legacy of their ties with Brazil in house names: there is a cottage named Nova Lima at Pool near Redruth; another house at Helston named Minas Gerais survived, until new owners unfortunately renamed it St Johns. As a child, I recall a gentleman living at Redruth who supported the Brazilian football team in every World Cup. He had been born at Morro Velho.

In the aftermath of the Brazilian Revolution of 1930, the once dense migration chains that bound Cornish communities with Morro Velho began to break down. Fewer Cornish were recruited as hard rock mining contracted across Cornwall.

But the Cornish legacy is still visible in the area around Nova Lima. The Protestant Cemetery containing many headstones is extant, as is the Anglican Church.

Contact with Britain brought a regimentation to life in Nova Lima and prompted changes in architectural styling, the use of more diverse furniture, new manners of dress, new cultural tastes, eating habits, practices of hygiene and of course, a passion for football.

Today, customs introduced by the Cornish miners such as tea taken with milk, and Christmas cake known as queca, are not found outside Nova Lima. In the town there are families who speak flawless English with no trace of an accent, and bear names such as Hosken and Roscoe.

Further Reading

For more information and references, see S.P. Schwartz, The Cornish in Latin America: ‘Cousin Jack’ and the New World (Cornubian Press, 2016).

M. Eakin, British Enterprise in Brazil: The St John d’El Rey Mining Company and the Morro Velho Gold Mine, 1830-1960 (London, 1989).

B. Hollowood, The Story of Morro Velho (1st ed. London, 1955).

R.F. Burton, Explorations in the Highlands of The Brazil Vol.1 (London 1869).

© Sharron P. Schwartz, 2021.

Pingback: A Cornishman in Chilecito, Argentina - Cousin Jacks World