Gongo Soco, Brazil

Unless otherwise stated, all content is © Sharron P. Schwartz, 2021, and may not be reproduced without permission

Gongo Soco, Brazil: An ‘English’ Village in the Tropics

I have a particular interest in Gongo Soco as William Merrett, born in Redruth in 1804, was a first cousin to Martha Merrett, my 3x great grandmother. William died suddenly in the village of Camargos near Marianna in 1835 or 36. Parts of a diary he kept detailing his passage to Brazil and arrival at Gongo Soco, and which was returned to his family in Cornwall, inform some of this article.

Gongo Soco is located in the mining state of Minas Gerais. It lies to the north east of the cities of Ouro Preto and Marianna, and is some 400km north of Rio de Janeiro. Gold was first found in a stream there in 1745. The land was later inherited by João Baptista Ferreira de Souza Coutinho, Baron of Catas Altas, and a ‘talho aberto’ (open cast) was commenced.

In 1825 the Baron sold the mine and surrounding lands for £79,000 to Edward Oxenford, a merchant and representative of the Imperial Brazilian Mining Association. This British company had been set up in 1824 at the height of the London Stock Market boom, with a capital of £100,000 divided into 10,000 shares of £100 each. The Brazilian Government collected a tax known as the ‘quinto’ (the royal fifth). That imposed on the Imperial Brazilian Mining Association was unusually high at 25 per cent of the gold extracted (this was later lowered until 1854 when foreigners were placed on the same footing as national industry and their labour was untaxed).

The First Significant Cornish Community in the Tropics

Cornish involvement in this company was evident from the very start, for its purchase had been recommended by Captain William Tregonning who had thoroughly explored the property with Oxenford. He was an experienced Gwennap mine captain who had left Cornwall with 30 mineworkers in the employ of the company in early-1825. More importantly, the Board of Directors included Michael Williams of Scorrier House, near Redruth in Cornwall, who was instrumental in recruiting hundreds of skilled Cornish mineworkers for the Company’s mines at Gongo Soco, Bananal and Cata Preta.

The mine proved to be incredibly rich. In the first 23 days, the washings of just five men produced 1,000oz of gold. For a considerable time from only seven fathoms depth below the old deep adit, 200lbs of gold was produced in each day’s working. The ore was found to produce over 80 per cent pure gold.

In the early days of the mine, much of the machinery and equipment used was supplied by Cornish foundries. This included waterwheels, stamp batteries, iron rails, chains, and sundry tools, which were exported largely through the Port of Falmouth. But as the company sought greater independence from distant supply lines, which was costly both in terms of time and money, the recruitment of skilled Cornish blacksmiths, wheelwrights and carpenters was increased. They built the water-powered machinery used for pumping, winding and crushing purposes on-site.

Getting there

Recruits took ship primarily from Falmouth (although some left from Liverpool). This important naval port was the station for the Royal Mail Packet Service. The Packet ships were usually lightly-armed and relied on speed for their security, with the captains able to also carry bullion, private goods and passengers. The Transatlantic crossing to Rio de Janeiro could take up to two months.

After clearing customs, Cornish migrants faced a month-long journey to the mine. There were two routes. The first entailed a boat journey across Guanabara Bay and then up the Rio Estrela which meandered through swampy terrain, to the Porto da Estrela (58km north of Rio). This was then an important port and the gateway to the rich mines of the interior.

From there, the journey was continued on mule inland to the foot of the Serra da Estrela (a prominent mountain range). The ascent of the mountainside via a zig-zag road took 2-3 days. This had been paved at great expense by Emperor Dom Pedro I (1822-31), but the earliest Cornish migrants would have faced a barely traversable quagmire of mud in the rainy season.

After crossing the River Parahiba by ferry-boat into the Province of Minas Gerais, travellers proceeded to Barbacena where the alternative land route joined the road to the mines. This second route from Rio was far longer, and traversed the towns of Vassouras, Valenca and Rio Preto. From Barbacena, the road continued through Ouro Branco, Ouro Preto, Marianna and then swung northwest to Gongo Soco.

The Cornish came to fear the river route. The boats which carried four people, their luggage and three or four mules, were easily capsized and there was the added danger of contracting yellow fever due to the swampy terrain.

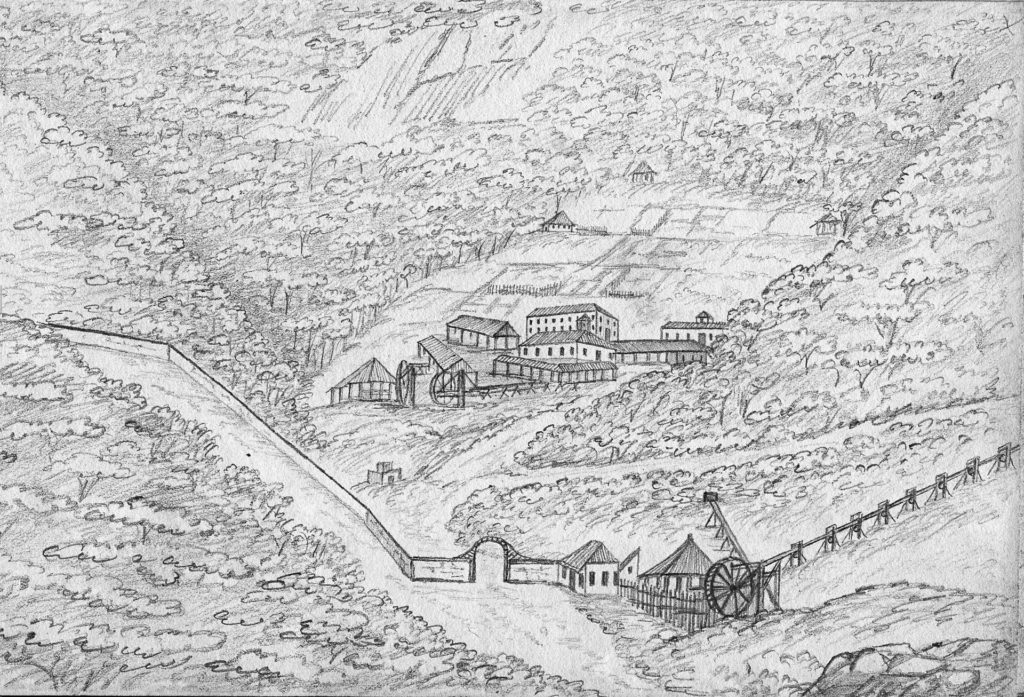

The Gongo Soco Mine

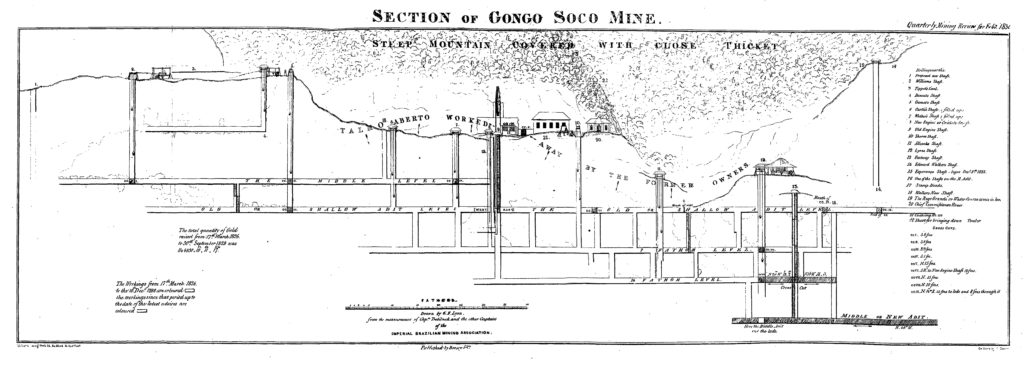

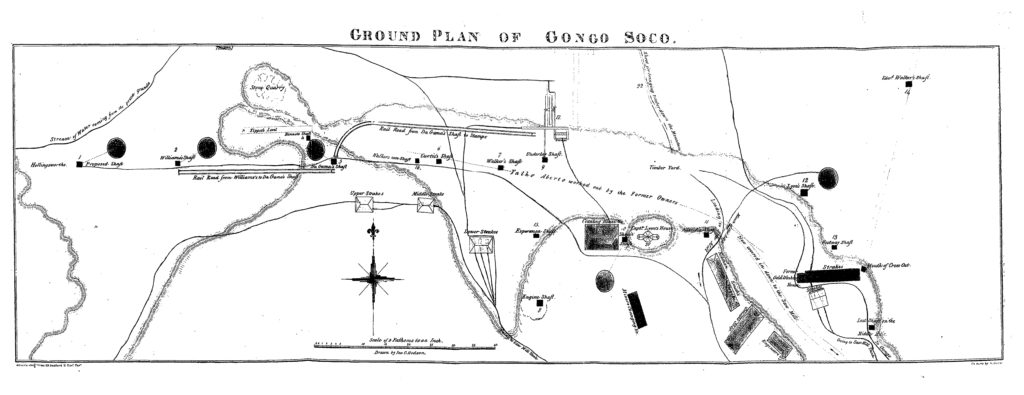

The centre of the mine lay inside a walled compound. An imposing arched gatehouse (built in 1834), which provided living quarters for 4 employees, lay at its entrance. Close to the arched gateway was the miner’s dry, consisting of washing and changing rooms and a Captain’s room. The slaves had separate facilities and were managed largely by their own feitors (overseers).

The workings were unwatered by a huge waterwheel which also powered the stamps. The water that was raised 330 feet (100m) to the surface was conducted downslope via launders to power a sawmill. A 6hp British-manufactured steam engine cast in sections had been imported in 1830, and took 45 days to reach the mine from Rio. It was apparently a single-cylinder portable model with a copper boiler, and was installed in a building above the main shaft. It did not commence working until the 30 December 1832. It turned a double wheel that drove a long chain to haul up kibbles of ore and to lower timber props to shore up the workings. This engine drew stuff from about 5 shafts (presumably via flatrods) and had replaced some 40 horses previously driving whims.

The workings at Gongo Soco were in jacotinga, a particularly friable rock formation, and considerable amounts of timber were required to make the workings safe. This was supplied from virgin forest about 6 miles (nearly 10 km) away. The company’s estate also included good tracts of arable land suitable for raising crops for the workforce, and fodder for bullocks that were used for hauling timber and supplies.

The tunnels leading to the stopes were about 6 feet (1.8 m) high and contained iron rails on which wagons were pushed for about 200 yards (180 m). The miners extracted the ore in time-honoured Cornish fashion, (double-jacking with drills and sledgehammers). The ore was then hoisted by the engine to the surface and transported in wagons by black slaves to the stamps. One slave could easily push two wagons.

The mine had nine water-powered stamp batteries, each containing 12–24 iron-shod vertical wooden shafts weighing 150 to 200 kilograms (330 to 440 lb) that crushed the ore. The ore-bearing slurry exited the stamps’ boxes in a fast current of water and passed into ‘strakes’. Here it was washed through grates over finely-woven cloth (or animal hides). The lighter sand was carried away in the stream of water, while the cloth or hides trapped the heaviest gold particles. These were washed in tanks to remove the gold.

The sediment was taken out in small batches and washed in a batea (wooden bowl) with a little water to separate the gold from the remaining impurities. This process was later replaced by the Tyrolese Zillerthal, a running amalgamation process of revolving-mills. Finally, the gold was dried in copper pans over a fire, then packed in leather bags ready for transport under armed guard to Rio. Here it was loaded onto the Packet ships for the Transatlantic passage to Falmouth. The washing of the ore was undertaken in a large building mainly by female slaves, and continued day and night under the watchful eye of guards.

There was also a large smithy or foundry where tools and equipment were made or repaired, and a big 3-storey warehouse holding provisions that also served as housing for the English miners. The first Commissioner also had his house within the complex and it also accommodated the Count House (office). An unusual feature of the compound was the gated entrance to the workings through which all the men had to enter and leave. This was constructed several years after the beginning of mining as an attempt to prevent the considerable theft of ore. Dogs were also chained up in this compound to prevent slaves and local people from breaking in at night to steal gold.

Close by was a stone-built blast furnace constructed by engineer, William Baird, with a waterwheel providing power to work a pair of bellows and a trip hammer. It was hoped that the company could produce their own iron using the high-grade local haematite to avoid over-reliance on imported ironwork and machinery, primarily from Cornwall. However, it was unsuccessful as high-grade haematite can only be smelted at high temperature. German mining engineer, Baron Wilhelm von Eschwige who was a graduate of the famous Freiburg Academy, was critical of its design and operation in his 1833 work, Pluto Brasiliense. The company eventually gave up trying to smelt its own ore, as it was found to be cheaper to purchase it from a foundry near Cata Branca.

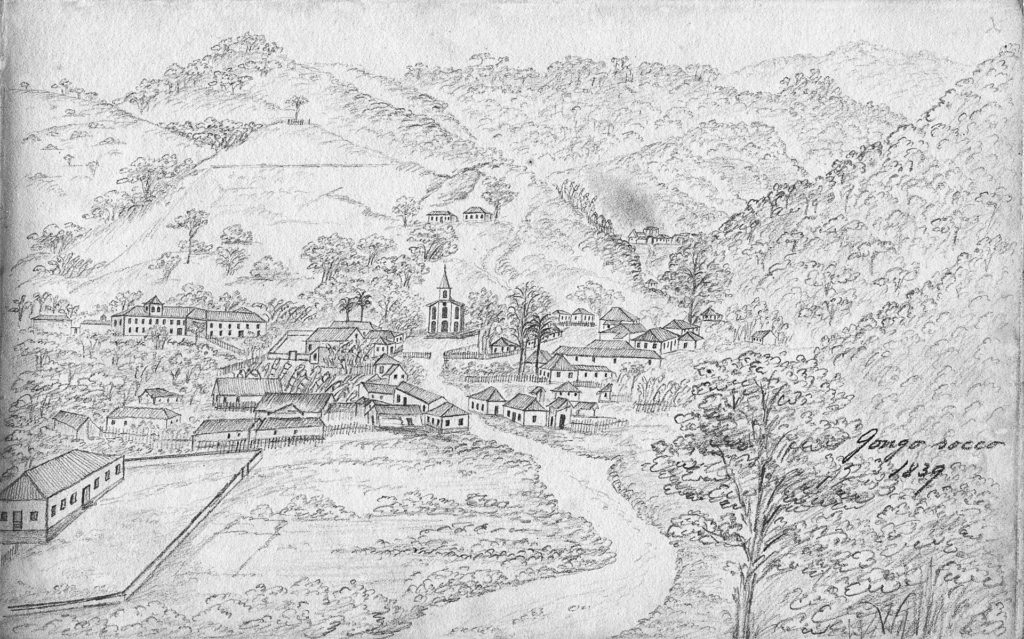

The Village of Gongo Soco

Gongo Soco rapidly became the largest gold mine in Brazil. Here, the first sizeable Cornish community in the tropics mushroomed some half a mile (less than a kilometre) from the mine and thrived for three decades. By 1830, there was an estimated 130 ‘English’ mineworkers in the company’s employ. The majority of these were Cornish, and some men brought their families over from Cornwall. The remainder of the 600-strong community was made up of male and female black slaves and free persons of colour.

Gongo Soco was situated at over 1,000m above sea level and was considered fairly healthy, with average temperatures ranging from 7-29 degrees centigrade. The area was quite picturesque with the surrounding countryside being a pleasant mixture of hill and dale. The mountains on the northern and western side of the valley, through which the Gongo Soco River ran, were thickly wooded.

At the foot of these mountains lay the village with its mainly single storey whitewashed buildings and small villas built by the company. The earliest houses were built of mud, but these proved difficult to keep in a good state of repair and were replaced with stone. The houses were clustered around an attractive Catholic church which had been built in 1829 and repaired in 1833. Its steeple was half hidden by banana trees. The ‘English’ were strictly segregated from the black workers according to the social conventions of the day, and resided in separate parts of the village.

A market was held every Saturday where the miners could buy their provisions. This was well-supplied with poultry, eggs, vegetables, and fruit. Reasonably priced butcher’s meat was supplied by the company and the mineworkers could take as much as they pleased, but it was not of high quality. In addition, there was a company store that sold a variety of non-perishable goods. Some unmarried Cornishmen hired a local woman to do their cooking. A lot of the Cornish residents created small gardens in front of their houses complete with lawns, and planted a variety of seeds from Cornwall to grow their own fruit, vegetables and flowers.

The company hospital resembled a barracks, but was carefully planned with central corridors, wards with two windows containing up to eight beds, and a sophisticated ventilation system to avoid humidity in the basement. The company doctor vaccinated the entire workforce against smallpox.

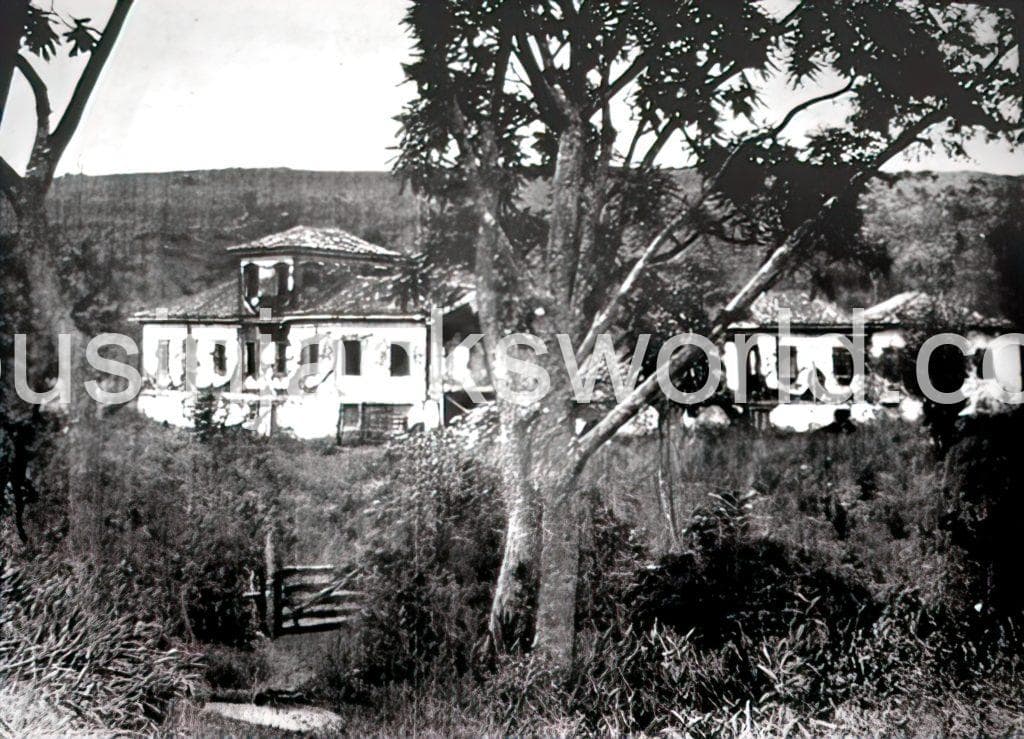

The Casa Grande, the former home of the Baron of Catas Altas, was extensively renovated by the company and described as a fine building, which served as the quarters for the Company Commissioner and senior management. It was famous for its hospitality, particularly the Saturday evening parties given by the Company Commissioner and his wife. Entertainment in the form of concerts with raffles and dances were held there.

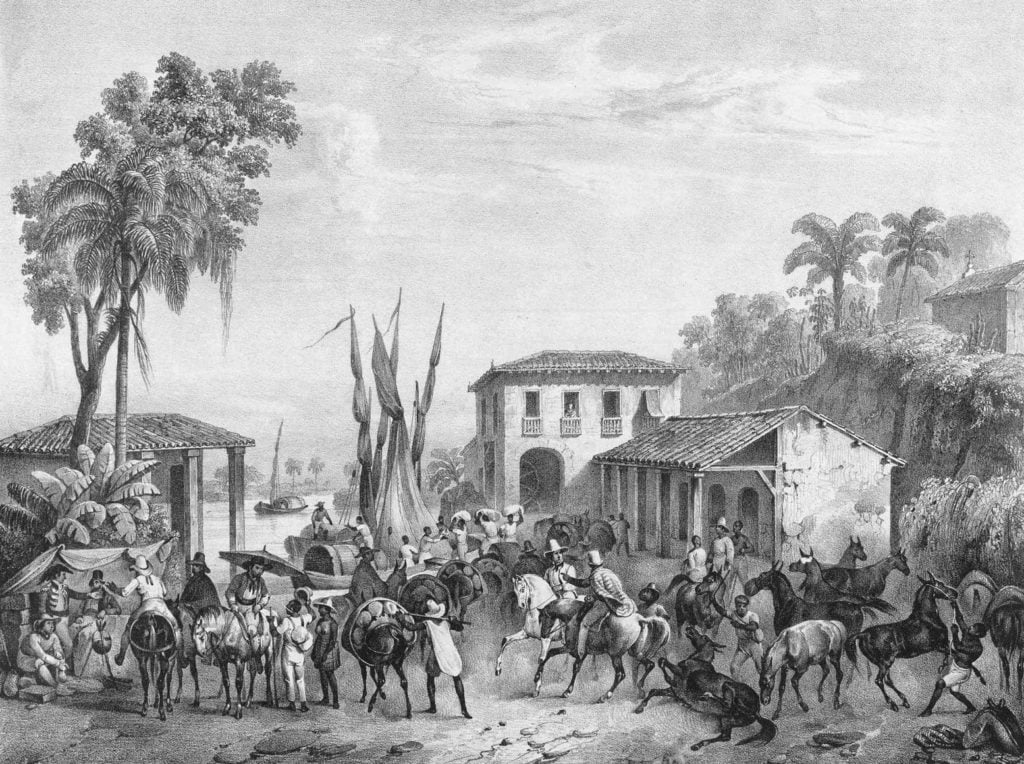

The facilities at the Casa Grande would certainly have been pressed into service for the 2-day visit of the Brazilian Emperor, Dom Pedro I. He arrived on 14 February 1831 with an entourage of 70, and twice as many mules and horses. He took everyone in his party, including the ladies, underground to inspect the workings.

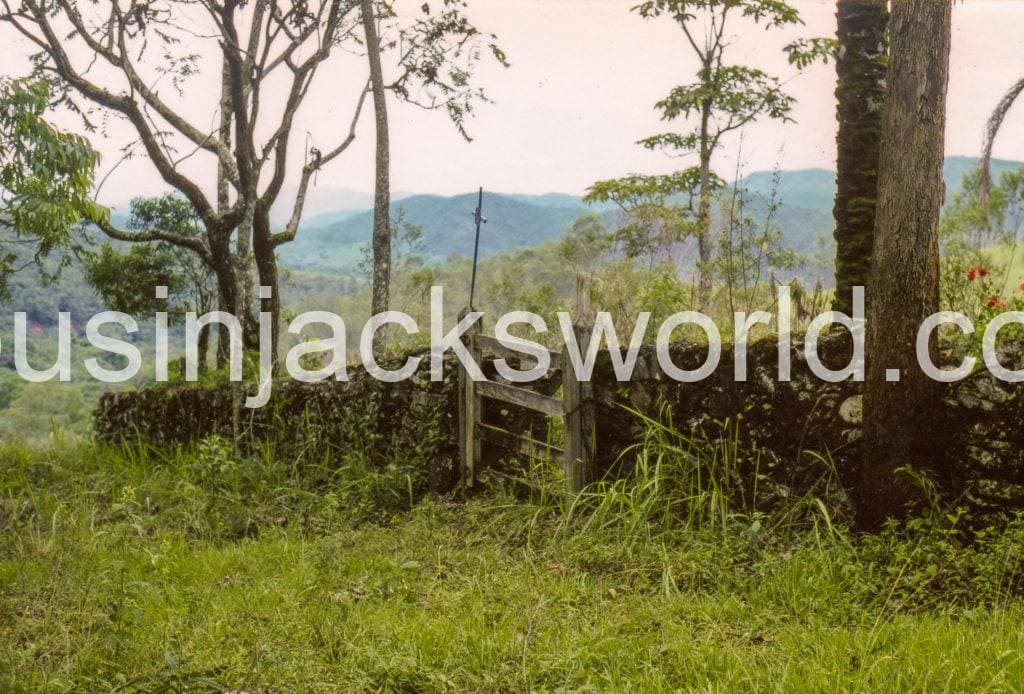

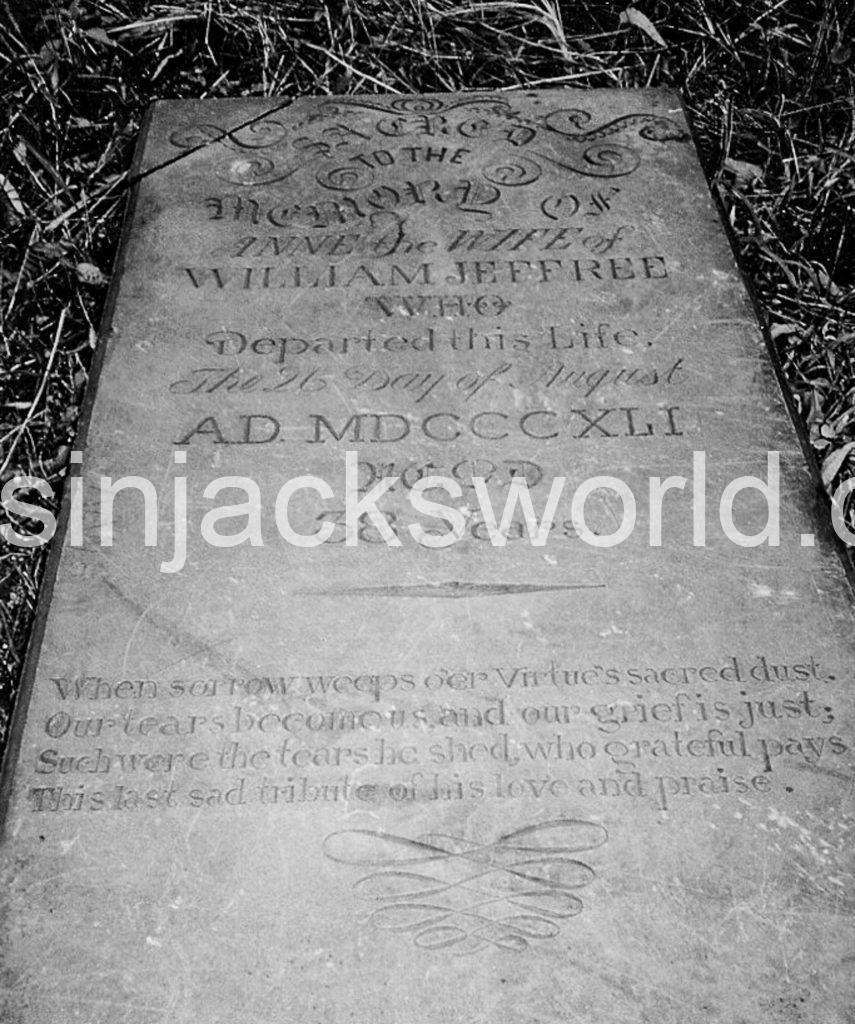

A library and reading room for the Gongo Soco Society was set up in the village. On holidays the Lagoa da Antas (Lake of Tapirs) some four miles from Gongo Soco was a favourite spot for the Cornish to have a picnic, and they enjoyed performing their national dances and songs. An Anglican church had been built in 1829-30, the same year that an English chaplain had been dispatched from London to administer to the spiritual comforts of the ‘English’ residents. Permission to create a separate burial place for non-Catholics was granted by Emperor Dom Pedro II. The Cemitério dos Ingleses was enclosed by a stone wall on a nearby hilltop. The earliest headstone dates from 1833, but there were inhumations prior to this.

However, as many of the Cornish mineworkers were followers of Methodism, they did not seem overly keen on the Anglican provision of worship, and held open-air prayer meetings some distance from the camp, as well as class meetings in their houses. By 1837, the Protestant church was beyond repair. It had been built at Grassagrandy, a place that was neither central nor easily accessible, and was probably not much used. In 1837 The Chief Commissioner decided to relocate this church to a more central location, and converted a building formerly used by the village stores for this purpose. An adjoining house served as the chaplain’s quarters.

This probably accounts for the fact that there was not always a chaplain at Gongo Soco, and the Mine Agent actually baptised some of the children born there. One of the Commissioners grumbled to the Board of Directors about the young men’s neglect of their religious duties and general dissipation on the Sabbath, and to a lack of moral guidance from those who were their elders or superiors.

The Question of Slavery

In 1843 there were estimated to have been around 100 Europeans, 100 free Brazilians and some 600 black slaves (both male and female) working the mine. Gongo Soco’s slave workforce had its own Captain responsible for their food, clothing, housing and discipline. Female slaves were largely employed on the dressing floors.

Britain abolished slavery in 1833 yet in countries like Brazil, where slavery was legal, British-owned mining companies employed slave labour. The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Association, with its goal of universal emancipation, campaigned for an end to this practice. In 1841 a series of damaging claims were made in the press regarding the Company’s abysmal treatment of its slaves, which were strenuously refuted by the Board of Directors. A group of Imperial Brazilian Mining Association shareholders published a letter to their fellow shareholders in the Mining Journal in 1841 calling for the Company to end to slave labour at its mines. The Board of Directors was angered by their blatant hypocrisy. All of their shareholders were well aware of the use of enslaved labour at Gongo Soco, but were happy to turn a blind eye when they pocketed their dividends.

The Company wasn’t short of support in high places. The shareholders’ concerns were swept aside and it wasn’t hard to dilute the 1841 petition presented to Parliament by Lord Brougham, a prominent abolitionist. Although the purchase of new slaves was banned, supporters of slave-owning mining companies successfully lobbied lawmakers to strike clauses prohibiting the renting of slaves.

The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Association then sought to stamp out the Atlantic slave trade by coercing Brazil to conform to the terms of the British-Brazilian Treaty of 1826, which it had ratified but failed to enforce. The Aberdeen Act of 1845 gave the Royal Navy authority to stop and search any Brazilian ship suspected of being a slave ship on the high seas, and to arrest slave traders caught on these ships. Moreover, the Act stipulated that arrested slave traders could be tried in British courts. This provoked outrage in Brazil, where it was seen as a violation of the free market, freedom of navigation, and an affront to Brazilian sovereignty and territorial integrity.

However, the Brazilian government knew that it could not afford to go to war with Britain, and popular sentiment against the slave trade in Brazil was growing. In September 1850, new legislation outlawing the slave trade was enacted, and this was enforced. As a result, the Brazilian slave trade ceased in the mid-1850s, although slavery itself was not abolished until 1888. This came too late for the slaves at Gongo Soco who were acquired by the St John D’El Rey Mining Company for the Morro Velho Mine. Brougham’s Act of 1843 was rendered toothless by the British mining companies operating in Brazil, who simply switched to renting slaves from local owners.

Cornishman, William Jory Henwood (1805-1875), who took up the post of Mine Agent with the Imperial Brazilian Mining Association at Gongo Soco in 1843, opposed the use of slave labour. He encouraged Cornishmen to bring at least their teenage sons with them, and better still, their wives and children, in order to raise the next generation of Cornish mineworkers in situ, thus lessening the need for slaves.

However, his ideas were not universally welcomed by the Board of Directors or the company’s shareholders, who feared that dispensing with slave labour would prove unprofitable, and ultimately ruinous, to the company. Henwood, however, continued to press for their emancipation, and did all he could to materially effect change for the better for the slave workforce. He opened a school for their children, encouraged and rewarded habits of thrift, cleanliness and sobriety, and saw to the emancipation of the most deserving adults.

An Early Transnational Community

As Cornish mineworkers were recruited on contracts ranging from 3-5 years, there was a constant turn-over of men who conveyed news back and forth across the Atlantic and carried letters and parcels for family and friends. Cornish miners received a yearly wage of £80 upwards, paid in monthly installments, ensuring that regular remittances flowed into Cornish banks for the maintenance of their families. The Mine Agent, and the under Mine Captains (usually around four in number), were paid far more. Skilled men such as engineers, assayers, ore-dressers, pitmen, timbermen, and the heads of various departments – Reduction, Smithery, Carpentry – were also on higher wages than regular miners.

Gongo Soco was, for three decades, an extremely well-known place in the mining towns and villages of the Gwennap-Redruth district in particular. But the Cornish community soon dispersed after the Imperial Brazilian Mining Company was wound up in 1856. Poor managerial decisions coupled with drainage problems conspired to the end the concern. Many men and their families returned to Cornwall while some remained in Brazil, signing on with the St John d’El Rey Mining Company at Morro Velho, or other mining concerns in Minas Gerais.

In 1867 Gongo Soco was reported as being slowly choked by nature which presented a truly melancholy sight to those who knew of its past glories. The mine was being worked on a small scale with 18 head of stamps and a few black labourers overseen by a feitor. The huge white stores were shut up and its gardens had been wasted by pigs. The Casa Grande, once as grand as any summer palace in Europe, looked abominably desolate and the steeple of the Catholic Church was shored up to prevent it from collapsing.

The nineteenth century census returns for parishes such as Gwennap betray the links with this village in Brazil, as scores of children were born there. The mine attained a legendary status among those who worked there. Between 1826-1856, it had produced over 12,000 kilograms (26,000 lb) of gold and netted almost £1,500,000. Tales of its richness and of the ingenious ways in which people managed to smuggle gold dust from the mine hidden inside biscuit tins and gun barrels, were still being told round Cornish fireplaces decades later.

Extant Remains

The majority of the mine buildings, waterwheel pits and other industrial structures have been swallowed by recent open cast mining for iron ore. In the village, the walling of several of the buildings, including the Catholic Church, hospital, and Casa Grande are visible, as well as the stone-walled Cemitério dos Ingleses. This contains 10 extant headstones, the majority of which have been vandalised. Some contain flowery epitaphs and mark the final resting places of Cornish people. It is notable that these were beautifully carved by William Raby from Carharrack, Gwennap, a sobering reminder that this is a part of Brazil that remains forever Cornish.

Further Reading

For more information and references, see S.P. Schwartz, The Cornish in Latin America: ‘Cousin Jack’ and the New World (Cornubian Press, 2016).

Débora Bendocchi Alves, Ernst Hasenclever em Gongo-Soco: exploração inglesa nas minas de ouro em Minas Gerais no século XIX ( Hist. cienc. saude-Manguinhos 21 (1) 2014)

© Sharron P. Schwartz, 2021.

Pingback: A Cornishman in Chilecito, Argentina - Cousin Jacks World