The Cornish at the Pozo Rico Mines, Guadalcanal, Spain

Unless otherwise stated, all content is © Sharron P. Schwartz, 2021, and may not be reproduced without permission

The Chequered History of Pozo Rico, the ‘Spanish Potosi’

The Guadalcanal silver mines lie in the Sierra Norte close to the border with Extremadura, just over 80 km to the north of Seville. Mining here has a long and illustrious history, and has involved many famous names in the annals of Spanish mining history.

In 1555, a long-abandoned silver mine was discovered less than 5 km from the town of Guadalcanal by two men named Martin and Gonzalo Delgado. They began raising quantities of rich silver ore, a fact that came to the attention of Princess Jane, Regent of Phillip II, who in October 1855 instructed the Marquis of Falces, Governor of the Province of Leon, to examine the mines and halt all extraction of mineral. The ores were assayed and found to be incredibly rich, containing 25lbs of pure silver per quintal of ore. Realising its potential, Falces took possession of the mine for the Crown.

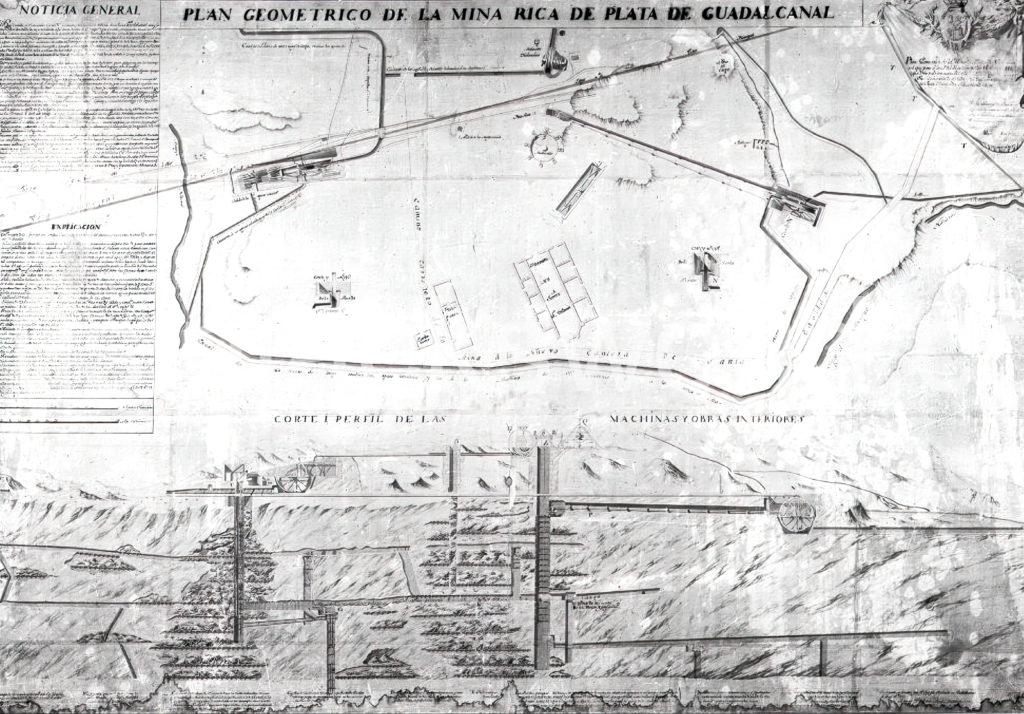

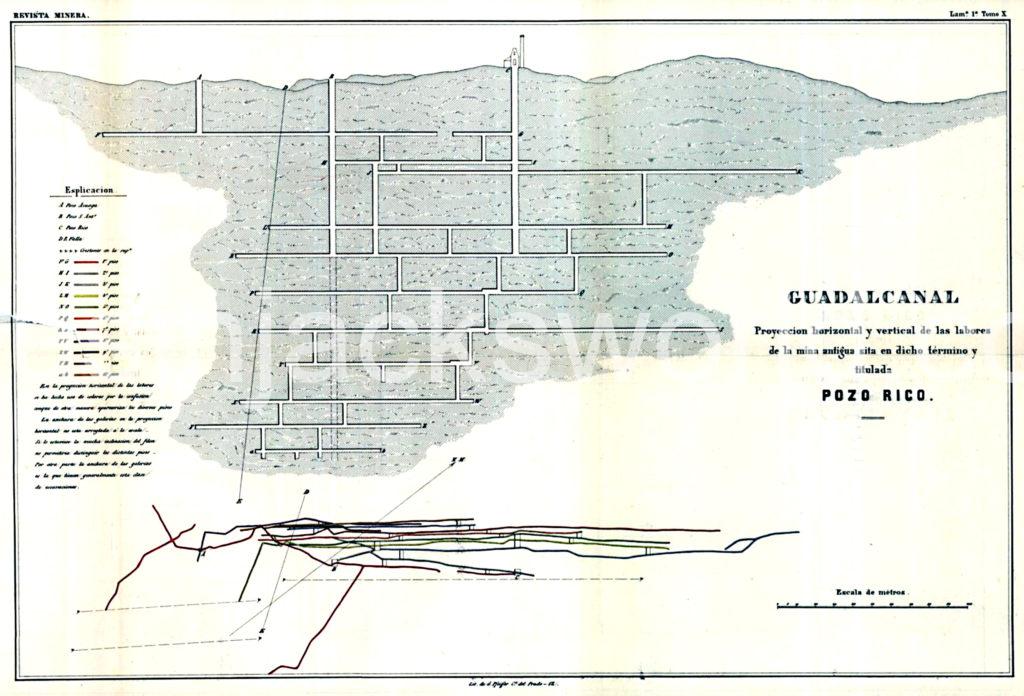

A commission to work the mines was then issued to Augustin de Zarate, a faithful servant of the Crown, who, with two Germans, John de Xumon and John de Xedler, proceeded to Gaudalcanal. They confirmed its spectacular richness, and it became known as Pozo Rico, after the famous Cerro Rico Mine in Potosi, Bolivia. From 1556-1576 the mine was worked by the Spanish government, but it proved impossible to prevent flooding, and it was abandoned.

Vast sums were expended attempting to unwater and restart the mine in the early 17th without success, until 1632 when a contract was entered into with the Fugger Brothers, rich bankers and entrepreneurs from Germany. They drove the mine to over 180m deep, producing immense profits for themselves and the Crown.

But rumours of fraudulent activity soon surfaced. The Fuggers were accused of secretly removing ore from the mine to deprive the Crown of its dues. A royal commission was issued to the Crown’s assayer to inspect the mine. However, upon leaning of the impending inspection, the Fuggar’s agents turned off the pumps, rapidly inundating the workings.

Attempts to work the mine using slave labour were made in the closing decades of the seventeenth century, but the next real chapter in the mine’s history began in 1725 when the Compañia Española was formed in Madrid in conjunction with a Swede named Lieberto Wolters. He introduced new drainage machinery and imported labour from Sweden to revitalise the mines, before his death and subsequent litigation which split the company, leaving Wolters’ heir with control of the Rio Tinto Mines, and the Compañia Española with the mines of Guadalcanal.

The Compañia Española then entered into an agreement to drain and reopen the mine with Lady Mary Herbert de Powis, who came from a prominent Catholic family in Wales, and who had emigrated to Spain where she had opened up several rich mines in Asturias.

Joining forces with her husband, Count Joseph Gage, they agreed to raise enough capital to restart the mine. They were to receive $200,000 when the mine began operating, along with half of the profits from the sale of ore. This was likely to have been the first instance of British involvement in the Spanish mining industry.

Lady Mary managed to raise sufficient funds to assemble a 400 strong mining team which included men from Britain and France, and had successfully drained the mine by 1732. However, the Compañia Española was unable to honour its agreement and development stalled, prompting Lady Mary to take legal action against the company.

In 1740 she was awarded the Guadalcanal mining concession along with an interest in the Rio Tinto copper mines, where she became mired in even more legal issues. Unfortunely for her, immediately after his ascent to the Spanish throne, King Ferdinand VI withdrew her Royal Charter, depriving her of her mining rights.

The mines had again flooded by the time they passed into the hands of a French company which worked them until 1778. In the late-eighteenth century, German, Juan Martín Hoppensak, surveyed the mines and formed a company to exploit them, which foundered as a result of The War of Independence (1808-1814).

The Guadalcanal Silver Mining Association at Pozo Rico

The mines lay flooded and abandoned until a group of adventurers from Seville and Madrid attempted to work them in the 1830s with the aid of an old steam engine taken out of a small English steamer. This engine was not powerful enough to unwater the workings and after five years, their capital was exhausted.

Around this time, a Scottish entrepreneur named Duncan Shaw took an interest in the fabled Pozo Rico. Born in Inverness in 1819, he had arrived in Córdoba, Spain about 1844 and had been exploring the mineral potential of the Sierra Morena. At the end of September 1847, he had raised sufficient capital from a group of interested parties to go to the mines to undertake a survey of them with a Cornish Mine Captain named Sincock. Rich mineral specimens collected from the mine convinced the interested parties to raise another £500 to send Shaw to Spain to negotiate with the Spanish Government for the rights to work the Pozo Rico Mine and to lease it from its Spanish owners.

After inspecting the mineral property in July 1848, Shaw secured a contract to work pertenencias (mining claims) on five lodes: La Chaparral; Santa Castilla; Santa Victoria; Pozo Azuaga; and Pozo Rico. He then came to an agreement with the previous operators for the sale of the buildings, machinery, mining tools and coal stocks, for 120,000 reais, payable in set installments. The Guadalcanal Silver Mining Association was then set up with a capital of £10,000 in 4,000 shares, with Shaw appointed as its Superintendent. The setting up of this company marked the first significant British capital investment in ‘modern’ Andalucian hard rock mining.

The company recruited 15 Cornish mineworkers, and purchased all the mining tools and equipment necessary to restart the mines in Cornwall. One of the adventurers was Nicholas Harvey, from Harvey’s of Hayle Foundry. It is no surprise therefore to discover that his foundry supplied a 30-inch cylinder pumping engine to unwater Pozo Rico.

The first British steam engine exported to a Spanish Mine was a Boulton and Watt model which had been installed on the famous Almaden cinnabar mines in the late-eighteenth century. Although it was not the first Cornish-manufactured engine to be installed in a Spanish mine, as a Sims combined engine from Harvey’s had already been erected at Linares in 1844, the Pozo Rico engine was among the earliest.

This steam engine and the Cornish mineworkers and their equipment left Cornwall by two sloops on 9 September 1848 under the Direction of Mining Engineer, Captain William Michell.

Getting There

The Cornish mineworkers and mining machinery left the Port of Hayle bound for the Port of Seville which lay on the Guadalquivir River. From there, the equipment was taken 86km overland to the mines in the Sierra Norte.

A Singular Cornish Mining Custom in Andalucía

After an uneventful passage, all of the equipment and machinery was offloaded on the quay at Seville on 23 September. After some initial delays, the party with the engine set out for the mines on 13th September, passing over a new road that had been built for over 11km towards the town of Llerena to facilitate the passage of the engine. The party with the engine arrived safely at the mines on 13 November 1848.

By then the old steam engine on Pozo Rico Shaft had been removed and its engine house and boiler house had been demolished. A new engine house and boiler house had been built to receive the Harvey’s 30-inch engine. The whole workforce then set to work repairing and making good their accommodation, rehabilitating the engine shaft, erecting a capstan and shears, preparing the shaft, sinking pitwork, and assembling the engine and boiler.

In order to mark the start of the engine the Mine Superintendent Duncan Shaw and Captain Michell arranged an event which was typical on the Cornish mines. In order to foster good relations with the local population, they invited around 50 of the leading dignitaries from Guadalcanal, including the Alcade (Mayor), priests, lawyers and shopkeepers, to partake of a ceremonial dinner on Christmas Day 1848 to officially ‘open’ the engine. During this celebration, the engine would have been formally ‘christened’ with a bottle of port. There is, unfortunately, no record of the Pozo Rico engine’s name, but a description of this event, which must surely be the only one of its kind described in Spain, was reported in the Madrid newspaper, El Clamour Publico.

Indeed, news of this unusual event had spread like wildfire among the town’s inhabitants who all rushed to the mine on foot and on mules to witness the curious spectacle. Yet, however impressed they might have been at the superiority of British engineering skill and perseverance, many were skeptical as to whether the Guadalcanal Silver Mining Association and its new machine would see any more success than previous companies had.

After a speech by Duncan Shaw, Captain Michell gave the engineman the signal to start the engine which hissed and growled into life, and its large beam began to move the pump rods in the shaft. Huge torrents of water poured forth causing the crowd to rush towards the shaft to observe the pumps.

After four hours, Captain Michell ordered the engine to be stopped. Much to everyone’s delight, it had succeeded in lowering the water 5 feet in the shaft. The assembled dignitaries were regaled with a roast beef dinner, and many libations to the engine and company were made, while copious Spanish bonbons and cakes were passed among the crowd. The merriment continued all night with the singing of Spanish and English songs. The enthusiastic crowd were still celebrating the successful start of the engine as day broke across the Sierra Morena.

Developing the Pozo Rico Mine

In one month, the engine working at 2-3 strokes per minute, had succeeded in draining Pozo Rico to the 31-fathom level. However, it was discovered that the shaft was no longer perpendicular past this depth, but diagonal, following the dip of the lode. This necessitated the procurement of some additional machinery (an angle bob) which was manufactured at the nearby foundry of Pedrosa. The installation of this and the shuttering of the shaft, undertaken by six sumpmen, temporarily retarded pumping operations.

Some very favourable ore specimens had been sent to England for analysis, and the Cornish engine was slowly draining the Pozo Rico, San Antonio and Pozo Marmolitos workings. In March 1849 twenty more Cornish mineworkers were dispatched to the mine. They arrived on 11 April by which time the water had been forked to the 51-fathom level and they began clearing out the old levels in Pozo Rico, as well as Pozo Azuaga, where a whim had been set up.

Captain Michell had inspected the 31-fathom level and was of the opinion that the main part of the lode to the south remained unworked. Finding that the Pozo Rico Lode passed into an area not covered by their lease of the property, they announced the acquisition of three new pertenencias: San Guillermo, Santa Rosalia and La Bonita, the latter of which Captain Michell believed would prove to be a new Pozo Rico. The colony at the mine consisted of 38 people, predominantly Cornish, all of whom were in good health. Excellent relations existed between them and the resident population.

At the first Annual General Meeting, it was noted that the company had expended more than half of its working capital, but the Board appeared unconcerned as this was deemed sufficient until such time as the mine began to pay its way. The Spanish company from whom the mine was leased had agreed to finance one third of the cost of erecting dressing machinery, which indicated their faith in the British venture.

However, Spanish law forbade the export of ore in its raw state which meant that the company either had to sell it at the mine, which would have resulted in a great depreciation in its value, or to transport it to Seville for sale, again at great cost. The only solution seemed to be smelting it on site. But it would have cost the company somewhere in the region of £5,000 to build a smelting works, and with current expenditure running at £400 per month, there were only reserves to continue for 5-6 months. Moreover, the company had just paid a £700 installment to the Spanish company as agreed in the contract they had signed.

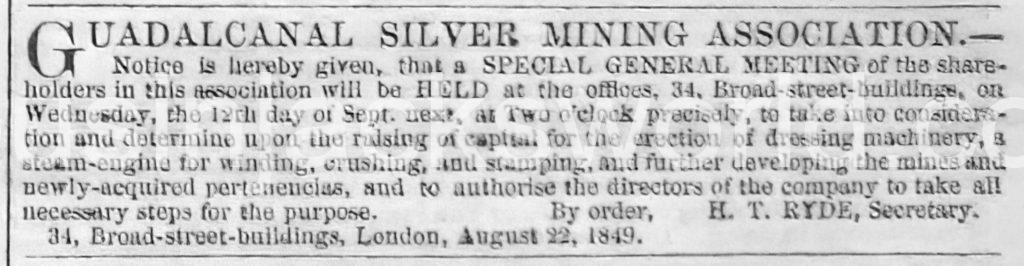

By September the company was exploring ways to attract £5,000 in additional capital in 2,000 shares, in order to purchase and erect a steam engine for winding, crushing and stamping, as well as the acquisition of new drainage and ore dressing machinery.

Failed Reboot

But before the Directors entered into any commitment in this respect, they arranged for a report on the mines to be undertaken by two Cornish mining captains, Henry Thomas and Matthew Curry, who were involved with another of Shaw’s Andalusian mining ventures at Linares. They recommended continuing to unwater the mine to its lowest levels, but that in order to effect better haulage and communication with the surface, the San Antonio Shaft should be deepened. They estimated the work would take another 8 months.

At the half yearly meeting in November 1849, the writing was on the wall. Although progress had been made in deepening the San Antonio Shaft and in unwatering the mine to the 92fm level, the capital available to the company was insufficient to cover the pumping and development costs. Alarmingly, the market uptake of the 2,000 additional shares fell well short of what was needed to continue operations. Concern was expressed for the welfare of the Cornish mineworkers at Pozo Rico, and who would be liable for their passages home if the venture collapsed.

In March 1850, a special meeting of the company was held in London to approve an application to have the company registered as a joint stock company. Its intention was to unwater and work the Guadalcanal Mines and to smelt the ores it produced. A capital of £30,000 was sought, divided into 6,000 shares of £5 of which 4,000 were to be ordinary shares, and 2,000 preference shares, power being taken in necessary to increase the capital to £100,000. The 2,000 preference shares were to take one fourth of all net profits, after which the remaining three fourths were to be divided over the whole 6,000 shares.

Among other clauses, it was stipulated that any additional capital must be raised by the creation of shares agreed by a general meeting of shareholders, and that the company could only be dissolved by a two thirds majority by resolutions taken at two general meetings. By now, Duncan Shaw seems to have wisely departed the scene, as he had bigger fish to fry at the Pozo Ancho lead mine, which was situated near the town of Linares to the east of Guadalcanal.

It was planned to dispatch a Cornish mining captain named Rule to Pozo Rico to compile a new report ahead of attempts to relaunch the company, but there were insufficient funds to do so. Messrs. Lamert offered to advance £150 for this purpose, and pledged that if Captain Rule’s report was favourable, they would have no problem in immediately raising £5,000 -£10,000 to continue work at the mines.

By July 1850, Rule had indeed made his report stating that £3,500 would be sufficient to prove the mine and work it for a year. The time had arrived to either obtain a fresh injection of capital or to let the mine die a natural death. It seems there was little appetite for sinking endless capital into a venture that never looked like making a profit. The concern was finally wound up in July 1852.

What happened to the Cornish mineworkers is unclear, as the company had an obligation to ensure their passage back to Cornwall. It seems highly plausible that some of them might well have been recruited by Duncan Shaw for his Pozo Ancho Mine, or were employed by other companies in this important district. Captain William Michell was certainly still in Spain in 1854, when he commented on the Las Infantas Lead Mining Company which was working mines near Linares. The Harvey’s of Hayle pumping engine on Pozo Rico Shaft might also have made its way to the rapidly developing lead mines of Linares.

A steam engine for pumping, winding and crushing which was discussed by the company in the summer of 1849 was possibly even ordered at Harveys. A 13’’/22’’ engine made for a concern in Spain was instead sold to Wheal Crebor in 1849.

Further Reading

Octavio Puche Riart, Algunos datos históricos sobre la mina de plata de pozo rico (Guadalcanal, Sevilla), De re metallica : revista de la Sociedad Española para la Defensa del Patrimonio Geológico y Minero , Nº. 25, (Madrid, 2015, pp. 27-52).